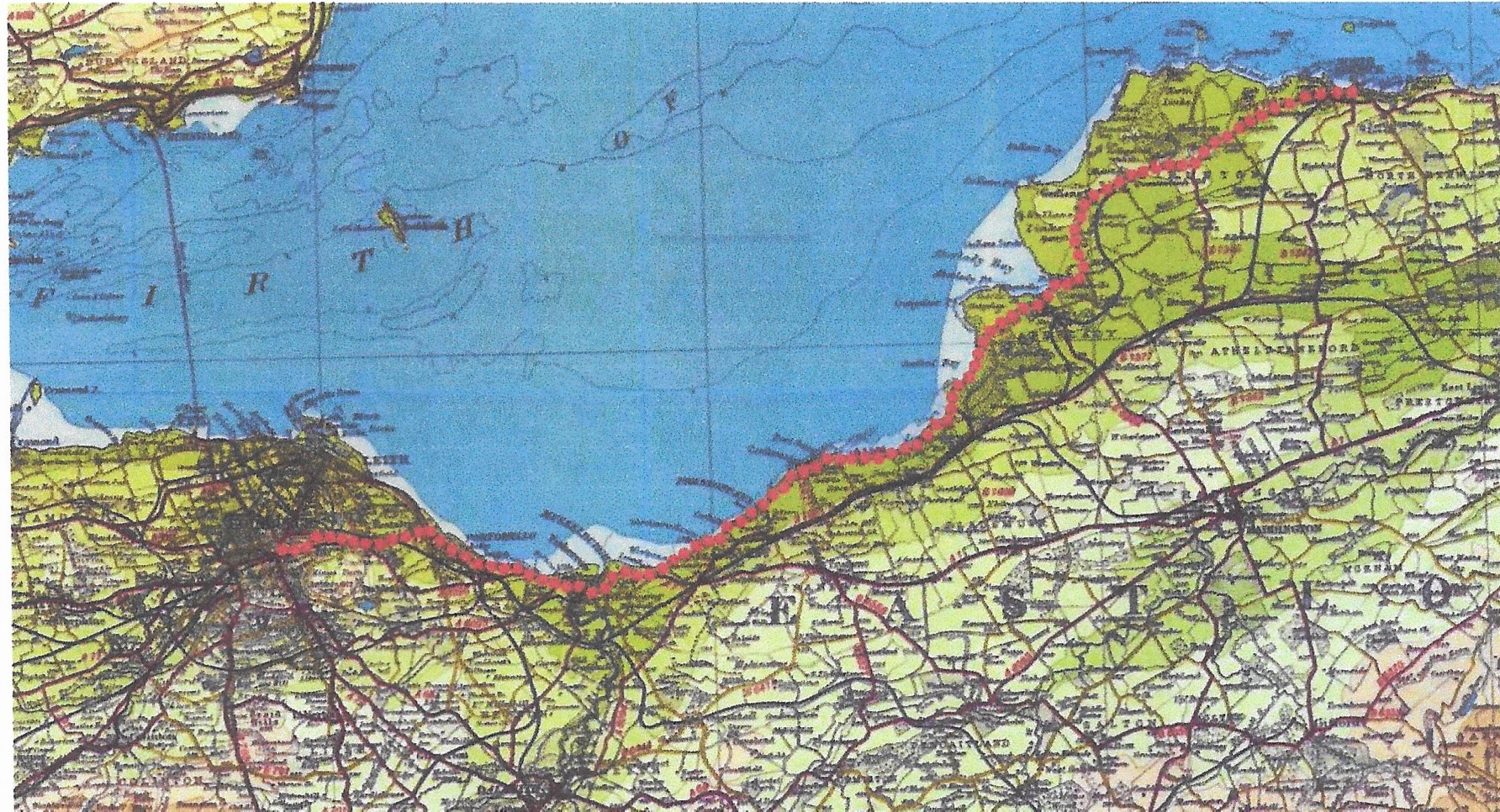

The original route of the North Berwick to Edinburgh race.

They were impressionable young men. Old enough to remember the childhood privations of war but too young to recall what went before. But even in the years before the war, marathon running had been little more than a fringe sport that led a Cindarella-like existence. The 1908 Olympic Games had, thanks to the futile heroics of a dehydrated and strung-out confectioner from Capri, elevated the marathon to a certain popularity north of the border. While the professionals had embraced its commercial appeal, the Amero-Canadian Hans Holmer notably setting a professional world record on the cinders at Powderhall in 1911, the fervour in amateur circles had, with few exceptions, been relatively short-lived. The number of important amateur marathon races in Scotland since the London Olympiad could be counted on one hand: a 15-mile “Marathon” from Dalkeith to the Scottish National Exhibition Grounds at Saughton in 1908, a 20-mile “Marathon” from Stonehouse to Hampden Park in 1909; a 16-mile “National Marathon Race” at Glasgow in 1911, where runners from south of the border filled the first seven places; an Olympic trial at Glasgow in 1912 that was ignored by the A.A.A. selection committee; and, in 1923, a full-fledged marathon race from Fvyie Castle to Aberdeen that unearthed a rough diamond in Dunky Wright. Lately the marathon had been on people’s lips again, garnering press coverage and building a grassroots following thanks to Wright’s triumph in the 1924 London Polytechnic Marathon and Olympic Trial. A spindly little Glaswegian runner would become an unlikely anti-hero in a hungry nation starved of sporting role models.

It was astonishing at all that Scottish marathon runners could even make a ripple on the British scene, let alone shake it up. For unlike their English brethren, they had no national association behind their endeavours and would have to wait until 1946 to crown their first national champion.

In the early 1920s the clubs in the East were short on long-distance running talent, the war having taken its toll on some of their numbers. The numbers had been less depleted in the West thanks to the proliferation of essential war occupations in the Clydeside area. The consequence of this was that athletes from the West of Scotland enjoyed an unbroken run of success in the national cross-country and 10-mile track championships between 1920 and 1927. In the pre-war years, Edinburgh clubs were still able to hold their own in the long-distance stakes thanks to outstanding runners such as Tom Jack, John Ranken and Jimmy Duffy, but those heady days seemed to be over for the time being at least. Aberdeen was the sole eastern bastion of long-distance running, the Aberdeenshire Harriers and Aberdeen Y.M.C.A. clubs having resumed their annual “marathon” fixtures after the War. Apart perhaps from Alex King, however, none of the men from the Granite City could make a compelling case for national honours.

Into this void stepped Canon Athletic Sports Club, a new club formed at Canongate (hence the name), Edinburgh, in 1922. They recruited their membership largely from the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders regiment stationed at Redford Barracks, where the training facilities were the envy of other Edinburgh clubs. What set them apart was that they also catered to hill and road running, “indulgences” the more established clubs were reluctant to entertain. It was not as if Canon ASC were ahead of their time because road races had enjoyed some measure of popularity during the Marathon Craze in the years preceding the war. During the 13 years of their existence, before they changed their name to Edinburgh Eastern Harriers, who in turn merged with Edinburgh Harriers and Edinburgh Northern Harriers to form Edinburgh Athletic Club in 1961, they instituted several popular, long-running fixtures. Among its members was one Willie Carmichael, an enterprising young sprinter, a visionary with organisational talent who would later become an influential figure in Scottish amateur athletics (http://www.anentscottishrunning.com/willie-carmichael/). Their most famous member was the John T. Suttie-Smith, the noted Dundee runner, who joined in 1932 as the Scottish cross-country champion and 10-mile record holder. The Arthur’s Seat Hill Race and the Queen’s Drive Races, for example, were the brainchild of Canon ASC. Likewise the first full-distance marathon race for amateurs in Edinburgh. Ironically, their most enduring legacy would be an event they did not institute: the race from Edinburgh to North Berwick.

Late in 1925 a small band of Canon ASC runners centred around the 21-year-old Lance-Corporal Edward Hoare Fernie began looking into the possibility of running the 22-mile route from North Berwick to Edinburgh as a time trial rather than a full-blown race. Of course, it was not a marathon run in the classic sense, but neither was it a world away from it. In fact, it happened to be almost identical to the distance that the messenger Thersipus is said to have covered from the battlefield of Marathon to Athens to announce the victory over the Persians in 490 BC. And it was without doubt a tougher test of endurance than the Powderhall race, which had been downsized from 26.2 miles to a mere 10 miles while hanging on to the grand “Marathon” tag.

Fernie, a stonemason from Falkirk, is said to have been a cousin of the 1932 Olympic marathon silver medallist Sam Ferris and was evidently cut from a similar cloth to his famous relative. On New Year’s Day 1926 he took advantage of the quiet roads on the morning after Hogmany for his undertaking. The run started at North Berwick P.O. and went along the coastal road to Edinburgh via Dirleton, Gullane, Aberlady, Longniddry, Prestonpans and Musselburgh, and ended opposite Edinburgh G.P.O. at Waterloo Place, a distance of exactly twenty-two and seven-eighth miles or 36.8 km in metric units. Accompanied by a motor car and his club mates W. Simpson and A. Good as pacemakers, Fernie ran a steady race and finished the course in 2 h 54 mins. He arrived covered in mud, but comparatively fresh, despite the heavy going on the still unpaved section between Longniddy and Musselburgh.

Local and even some regional newspapers covered the race and aroused unexpected interest. Members of the other Edinburgh running clubs evidently felt called upon to take up the challenge. In March 1926 Dr. A. Millar of the Edinburgh University Hare and Hounds launched an attack on the course record, but broke down on King’s Road in Portobello and gave up after covering just over 20 miles in 2 h 37 mins. Another medical student at Edinburgh University, James D. Horsburgh, made the next record attempt on 17 April 1926. Horsburgh, a member of the Edinburgh Southern Harriers, used the favourable conditions to set a fast pace and at one point was 17 minutes ahead of record schedule. However, he too had misjudged his capabilities and was reduced to a crawl during the closing stages of the run, failing narrowly with a time of 2:55:15.

The great response prompted Fernie to undertake another solo run from North Berwick to Edinburgh on 13 November 1926. Despite a strong southwest wind, he managed to improve his own course record to 2:48:36 thanks to the active support of his club mates.

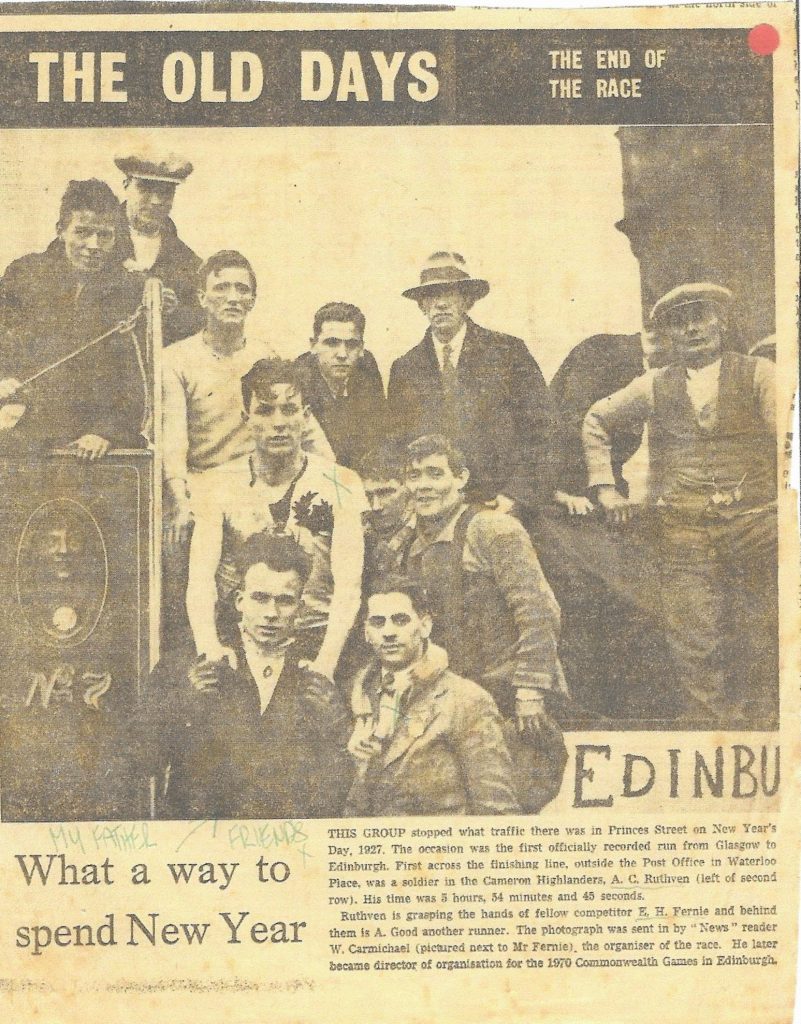

In 1927 the members of the Canon ASC undertook two more runs, albeit neither from North Berwick to Edinburgh. After Fernie was defeated by Andrew Ruthven in the 44 1/4 mile race from Glasgow to Edinburgh on New Year’s Day, he won the 26-mile 385-yard Canon ASC Marathon Race by a large margin in 3:26:06 on 6 August.

In 1928, however, interest in the North Berwick to Edinburgh run was reawakened when Edward Fernie undertook his third solo time trial. He got off to a good start by covering the first 4 ½ miles from North Berwick P.O. to Gullane in 26:30 min, then he passed Aberlady (7 ¼ miles) in 49 min, Prestonpans (13 ¼ miles) in 1 h 35 min and Levenhall (15 ¼ miles) in 1 h 50 min. Could he keep up the pace on the last part of the run through the eastern suburbs of Edinburgh? He struggled a little and lost some time but he still made it to the finish at Waterloo Square in a new record time of 2:45:24.

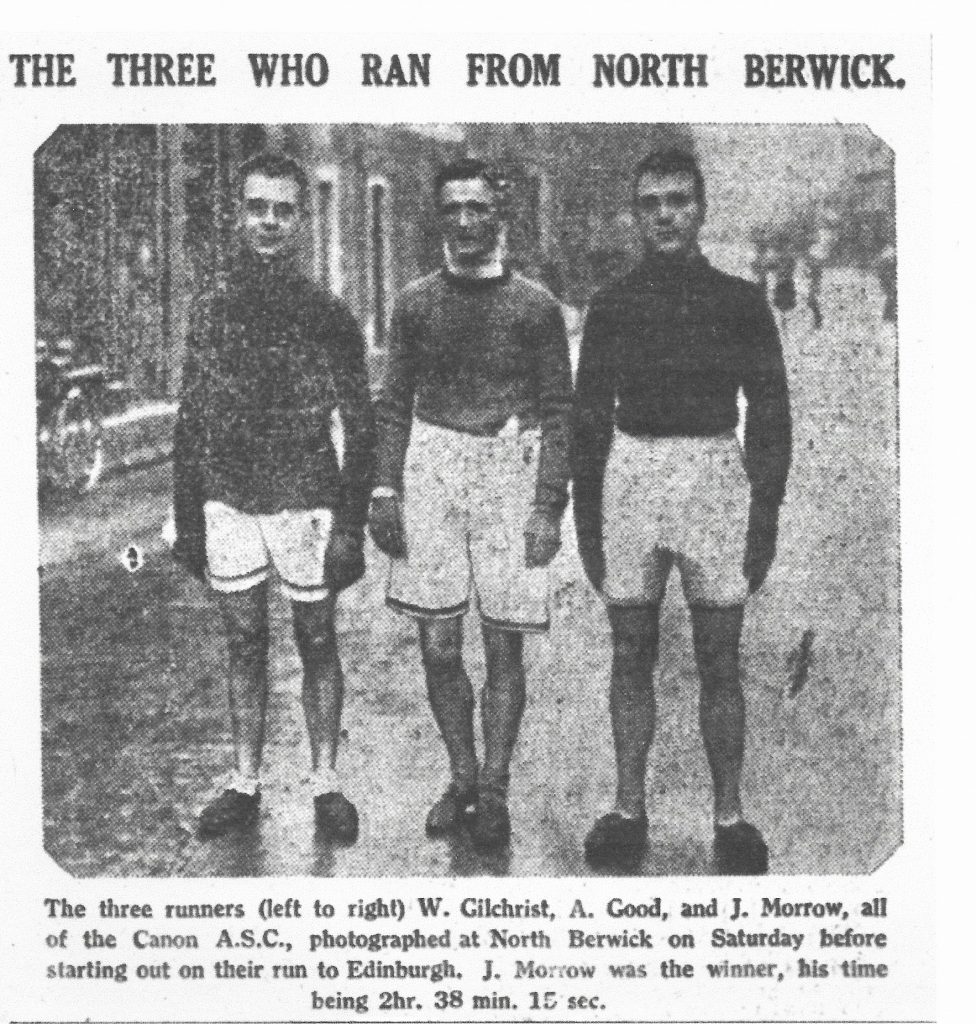

After Fernie’s departure, the North Berwick course record went unchallenged for a couple of years. Nevertheless, the rank and file of Canon ASC had not lost sight of the record or interest. On 22 February 1930, three members set out to erase Fernie’s record once and for all. This one was to be an actual race. The runners – W. Gilchrist, A. Good and J. Morrow – started from the North Berwick G.P.O. in ideal conditions and were accompanied by a considerable retinue of supporters, including the record holder. To save their strength for the last and most difficult part of the route from Portobello to the G.P.O., they started conservatively and were over four minutes behind the record at five miles. All three kept together until just beyond the Musselburgh town hall (about 17 miles) where Good dropped back due to a stitch. The race was decided at Piershill (about 20 miles) when Morrow broke away from Gilchrist. Morrow, a 4:47.8 miler in 1926, finished the last part of the Levenhall course eight minutes faster than Fernie and sprinted to the finish in new figures of 2:38:15. Gilchrist and Good also bettered the old record, running 2:39:50 and 2:44:25 respectively. Nearly two years later, on 2 January 1932, Morrow rang in the New Year with another attempt at a record. Despite stormy winds and pouring rain, he was on course for the record halfway through the race when the battle with the elements began to take its toll. In the hilly second half he slowed considerably but refused to give up and dragged himself to the finish in 3:00:41.

There was no further record attempt on the North Berwick route until December 9, 1953, when Joe McGhee, Scotland’s latest marathon sensation, did a solo time trial in the style of Edward Fernie 27 years previously. There is no other way to say it: he destroyed the course record! By completing the distance in 2:05:19.6 he gave a glimpse of the rare talent that would carry him to a shock victory a few months later at the Empire Games Marathon in Vancouver, Canada. It should be noted that McGhee ran the route in the opposite direction – from Edinburgh to North Berwick – to take advantage of the prevailing westerly wind.

When annual North Berwick to Edinburgh Road Race was inaugurated in 1958, the organisers also adopted the more advantageous west-east route. From the outset, the race was well received by the Scottish long distance elite, with the 1966 Commonwealth Marathon Champion Jim Alder among the early winners. The two-hour mark was broken for the first and only time in 1968, when strong winds blew Don MacGregor, 7th placed in the marathon at the 1972 Olympic Games, to a time of 1:59:57. Edward Fernie, the original course record holder, would have been amazed, but unfortunately he had died of pneumonia earlier that year. The 1969 race was the last on the original route. From 1970 onwards the race started at Meadowbank Stadium and was over a mile shorter at 21.7 miles. It was also run as a full-length marathon from 1971-73, and again in 1991.

The event continued each year as an irregular distance until 2009, when it changed into a measured 20-mile race from Portobello to North Berwick, continuing as such until 2017, after which it collapsed. In 2022 the famous race was successfully revived by Alan Lawson, best known for his 40+ years of staging the Seven Hills of Edinburgh event. He also managed to find the event’s (lost) trophy, below, which had originally been presented to the Scottish Marathon Club in 1960 by North Berwick Town Council.