For those of the present generation, the old notion of amateurism v professionalism is uncharted territory. Athletes in the twenty first century find it hard to imagine runners not getting money prizes – even children are able to win money in the Highland Games circuit. But for many, many years money was taboo. The belief, not entirely without foundation in their experience, brought corruption in its wake. In the 1890’s several athletes were banned for accepting expenses and schemes such as ‘ringing’ (several athletes agreeing among themselves to pool their prize money and then share it out between them) and deciding who was going to win were often indulged in. In the twenty first century with big money prizes on offer and obscene financial deals available to winners in the major Games has led to the abuse of drugs, etc. However the knock-on effect on everyday athletes was disproportionate. There is the famous story of the child who won a packet of fruit gums being banned from amateur athletics. I have just bought a book called “The Ghost Runner” by Bill Jones about John Tarrant who had, as a 17 year old got £17 in expenses as a boxer being totally banned from amateur athletics for life. He ran in races, having changed behind a hedge or some trees and more often than not won them. It’s a book worth reading. I’ll come back to him. Some of the situations experienced by athletes of the 50’s and 60’s are recounted below. The latest addition is about the late nineteenth century professionalism and corruption in the sport in Scotland and comes largely from the official history of the SAAA’s by John Keddie.

This first piece was written by Hugh Barrow on what was for a long time an aspect of the sport that we could have well done without. It was something that I knew about, disapproved of but which very seldom, if ever, bothered me. Hugh had a talent and attitude that brought it to his attention and the tailpiece of his article is most interesting – and the mindset is probably incomprehensible to the modern athlete. Hugh speaks:

Not so long ago, well maybe slightly longer ago than one would wish, there existed in Scottish athletics a form of apartheid between those who ran for money and those of the so-called amateur code and woe betide those who crossed the great divide. That sounds simple but it was certainly not that. A boy who accepted something like 20p in new money for a Sunday school race could lose his amateur status for life such was the draconian line taken by the Amateur authorities. All this stemmed from the birth of the SAAA in 1883 born as a reaction to corruption in Victorian athletics, sometimes called Pedestrianism, including drugs, betting and race fixing. Nothing new there you may say. From that time to the 1970’s that body (the SAAA) saw itself as the guardian of the amateur code and woe betide anybody who crossed the line. You were not even allowed to compete against the pros even though you yourself did not receive any cash prize such were the “contamination rules”. At one point you could not compete in amateur athletics if you were a PE teacher and professional footballers who went to Jordanhill College to train as teachers could not represent the College at athletics.

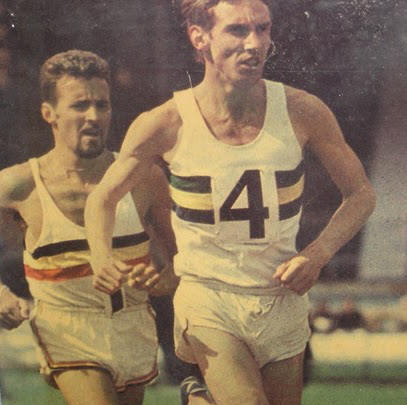

The professional meetings/games tended to be in the Highlands and in the Borders while the amateur meetings tended to be in the Central Belt. There were exceptions but that was the trend. The professional games were often more amateur in spirit that the amateur meetings. But that was the strangeness of it all. It all hinged round accepting prize money instead of prizes. Even though the prizes could well exceed the prize money, it was the principle. Ways of getting round the rules became part of the folklore. Whilst broken-time payments eased professionalism into soccer, and saw the birth of Rugby League, more devious methods were adopted in athletics. Amateur athletes sometimes ran under assumed names or in disguise at pro games to avoid the authorities. One well-known field events athlete was caught out by his photo appearing in a Glasgow paper even though he had changed his name for the day.

Of course at the top level, appearance money also came into play especially in Europe. One well-known Olympic gold medallist appeared in Dublin and proceeded to set a world record for which he was due a substantial purse.

Hugh appeared on the Scotsport television programme in 1966 (after all the hassle that Tarrant suffered as described below) and was contacted the following morning by Rab Foreman of the SAAA telling him that any money had to be repaid – Hugh had to send the cheque for £1:1:0 back to STV! The cheque and the letter are shown here – once the link is re-established, for a proper view, click on each picture in turn.

Hugh ran in many races in all sorts of places but on the subject of rewards for running and drawing in the crowds he has this to say about a race at Hawick in the mid 1960s: “In the aftermath of the Olympics in Tokyo in 1964, where both Alan Simpson (Rotherham) and John Whetton (Sutton) both made the final of the 1500m, they became the dominant force in British in the middle distance scene at a time when ‘invitation miles’ were highlights in the programme for many meetings the length and breadth of the country. However Whetton, the King of the Boards’, was dominant indoors and Simpson, the ‘Head Waiter’, dominated outdoors. This outdoors domination of Simpson led to promoters starting to lose interest in putting on invitation miles so it was felt that Whetton had to get an outdoor win over his rival to whet spectator appetite. So on a June Friday evening in 1965, we arrived at Mansefield Park, Hawick, for the Common Riding Invitation Mile. The field also included former world record holder Derek Ibbotson, along with the likes of Teviotdale’s Craig Douglas, VP’s Graham Peters and myself. It was felt that a Whetton win would help the attendance when the show rolled on to the Rockingham Miners’ Gala Day in Barnsley scheduled for the following day. On a tight five laps to the mile grass track laid out on the rugby pitch, such was the dominance of the dynamic duo, it was agreed that Whetton would edge out Simpson coming off the last bend. However Graham Peters was not in the script and boxed Whetton in. I can still hear him shout to Simpson that he had to go it alone. As commentator we had the legendary Bill McLaren and although he sure knew his rugby he was a bit off the pace when it came to running and got a bit confused by what was happening. probably just as well. For the record: 1. A Simpson 4:03.7; 2. J Whetton 4:04.4; 3. H Barrow 4:06.0

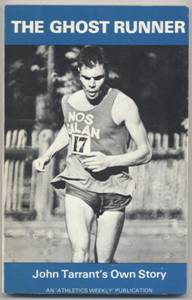

John Tarrant was a different case and his story is told in detail in the book referred to above and also in the earlier book produced by ‘Athletics Weekly’ shown here.

John as a young man was very energetic and took up boxing as an outlet for the energy and maybe anger at the hand he had been dealt as a child. It was a more glamorous sport than football with long reports on Randolph Turpin v Sugar Ray Robinson and the money available. He joined a local club and did some training, including roadwork, and was talked into a couple of bouts against friends in the same club and a couple of guys from other clubs. Altogether he gained £17 in expenses before he decided he would rather be a runner – he enjoyed the road work and had a natural talent. That meant joining a club so he applied to join Salford Harriers, his local club. He filled in the application and in the space asking if he had ever earned money for any sporting activity, he swithered for a long time before telling the truth. His form came back with his 5/- membership form – he couldn’t join. The area AAA’s Committee said that since he had been a boxer who had earned money he would have to be cleared by his local Amateur Boxing Association Committee. They had a reciprocal arrangement with them and could not accept him as an amateur unless the ABA gave him clearance. This was not forthcoming. he was desperately keen to run so he turned up at a couple of races in his vest and shorts but covered with a long overcoat and a cap pulled down over his eyes. When the race started he removed the ‘disguise’ and joined in. Officials tried to pull him out of the race without success and he led for most of it. The Express newspaper gave him the title of ‘The Ghost Runner’ because he ran without a number, never appeared in the results and was totally ignored by the establishment. He got on well with the other runners, spectators liked to see him in action and soon promoters realised that an appearance by the ghost added to the attraction of their race. As the momentum built up he was invited to appear on David Coleman’s Sportsnight programme. The interview was sympathetic and at the end he was wished good luck by Coleman. He was contacted by the AAA’s who asked for the money to be repaid! He was not an amateur by their lights but he couldn’t accept money for a TV interview. The sum involved was £1:18:0 [£1:90]. The Gordian Knot of acceptance as an amateur was cut by the recognition, rather late in the day, that since he had never ever actually been a paid up member of the ABA, he didn’t need their clearance! After three years of being a ghost, he was accepted into the amateur fold. [While he was banned and after the big movement for his clearance had really gained momentum, he had been invited to a race and instead of a number he wore a card reading ‘GHOST’] The new book is very good, the AW one is out of print but he was a remarkable man and I can’t recommend his story too highly for anyone wanting to know about the divide and more importantly about this man and his part in helping bring down the wall.

Graham MacIndoe sent these two links to articles about Tarrant:

and

http://www.bookdepository.co.uk/Ghost-Runner-Bill-Jones/978145966065

So there you have it!!! Hugh Barrow and John Tarrant both had to give back the money paid for a TV interview. The situation did provide some lighter moments – not always for officialdom, however.

For instance there was the time when AAA’s supremo Jack Crump went to Ireland in the immediate post-war period to investigate rumours of illegal payments being made to athletes. Following his investigation, he was about to board a flight back to London when somebody rushed forward and thrust a box of eggs into his hand and Press photographer snapped it for the record. The significance? Eggs were still rationed in Britain! No more was heard of that investigation!

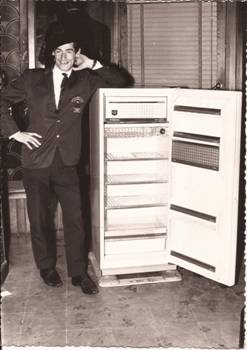

The Continental take on the ‘shamateur’ business was quite straightforward. When athletes travelled to their big races, the were awarded prizes such as refrigerators, washing machines, television sets, etc on the Saturday after the race; these ‘trophies’ were then sold at a special sale on the Sunday and the proceeds given to the owner (ie the runner who had won them! The picture below is of Lachie Stewart with his prize from the race at Elgoibar in Spain before he sold it on.

“On 2nd November 1893 the General Committee of the SAAA appointed a sub-Committee ‘to enquire into various alleged abuses in amateur athletics’. The sub-Committee comprised: Donald C Brown (West of Scotland Harriers) – vice president of the Association; Alex MacNab (Clydesdale Harriers); Farquhar Matheson (Abercorn FC); James Caw (Edinburgh Harriers) and David S Duncan (Royal High School FC) who acted as secretary. In the following two months the Committee held seven meetings – four in Glasgow and three in Edinburgh – at all of which various representatives of Sports-holding clubs, Association officials and prominent competitors were interviewed. In all, thirty one witnesses appeared before the Committee, three of whom were recalled, while signed statements were received from another three who were were unable to attend personally. All the evidence accumulated from these investigations was distilled into findings submitted to the General Committee on 15th January, 1894. These findings revealed a none-too-healthy state of affairs:

(1) The payment of competitors expenses, including Hotel expenses, was general throughout Scotland, but only in the case of prominent athletes from a distance. This applied particularly to prominent English athletes who appeared at meetings in Glasgow and Edinburgh but applied also to Scots athletes who competed at Blackburn and Sunderland at various times between 1889 and 1893l

(2) It was proved that payments of money had been made in particular to

AR Downer, the Scottish Champion sprinter, who not only had received £3 for ‘expenses’ in a meeting, but also had overtured for payments to several clubs. (Downer denied this but apparently his evidence was judged to be of a ‘very untruthful and unsatisfactory character’!)

S Duffus (Arbroath), an outstanding Scottish distance runner, who admitted to receiving £2 in the name of expenses from a club; and

TE Messenger (Salford), an Englisg sprinter who received £5 in the name of expenses from a club.

(3) It was found that a club had paid a round sum to an individual resident in England on account of ‘travelling expenses’ for a party of English athletes whose hotel expenses were also defrayed;

(4) In the west of Scotland payment of entry fees was not enforced by clubs as it ought to have been. This was mainly found to be the case with cycling entrants;

(5) Betting was prevalent in Edinburgh and Paisley, and was n the increase in Glasgow;

(6) ‘Roping’ was spreading and this, together with the betting was found to be demoralising amateur sport.

All the witnesses were given the assurance that no action would be taken against clubs or individuals for any infringements which had come to light. That immunity protected the athletes cited. Downer and Messenger later turned professional and the former, in his ‘Running Recollections’ (which appeared after he had turned pro) lifted the lid on the hypocrisy abroad in his amateur days. Thus in the course of a decade of its life, the Association had passed from a state of idealism to one which revealed the stark materialism which had permeated amateur sport. But still more testing times were ahead!”