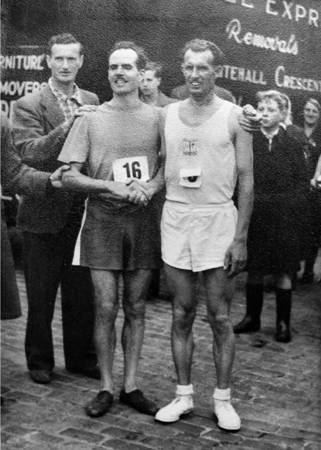

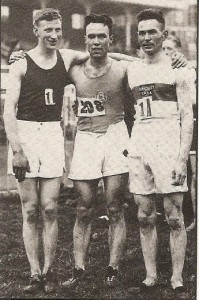

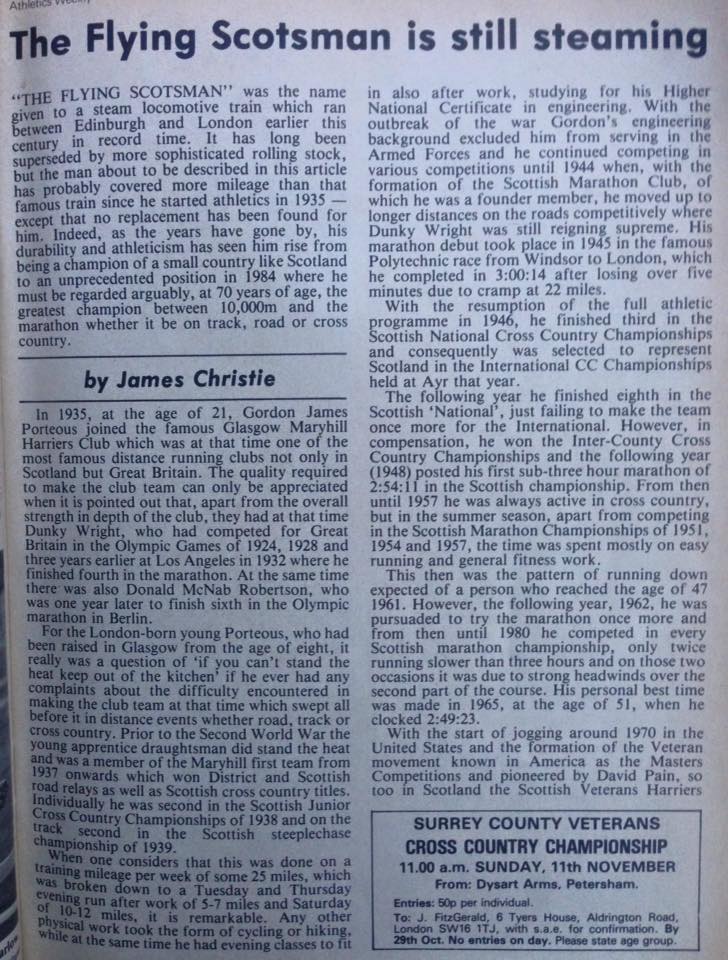

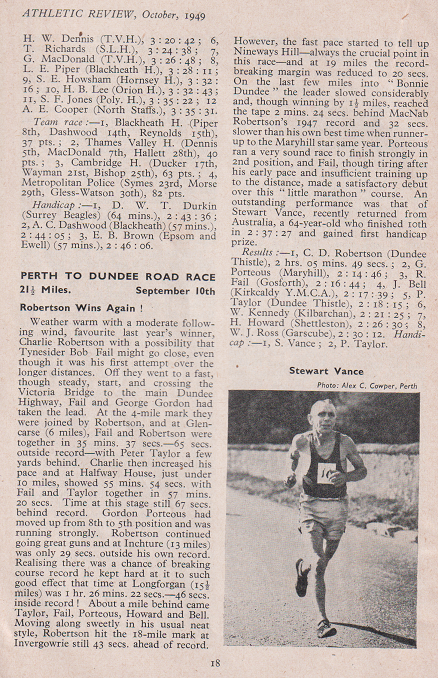

Winner Charlie Robertson offers his congratulations to John Duffy (right) runner-up

after the 1952 Scottish Marathon Championship from Perth to Dundee

Jock Duffy must be one of Scotland’s least known marathon champions. Alex Wilson has written the following account of this fascinating man and we thank him for it.

*

Several passages are, with permission, quoted verbatim from “The Hardy Race: The Scottish Marathon Championship, 1946 – 2000” by Fraser Clyne and Colin Youngson. Colin also kindly helped with checking this article.

JOCK DUFFY: A BRICKLAYER’S TALE

Asked what he thought about being labelled an “Anglo Scot” back in the day, Jock laughed and replied, “Not very much, actually.” What real Scot would? John Duffy was born in Broxburn, West Lothian on December 13th, 1919. His parents called him John but practically everyone else knew him as Jock, especially in Essex where all Scotsmen are Jocks! Broxburn was a small shale mining community in those days, and, immediately after leaving school, Jock inevitably became a miner like his father before him. He did not take up running competitively until joining the Army. To this day he remembers the exact date of his enlistment: May 16th, 1940. These were desperate times. British troops were on the retreat from Hitler’s advancing armies, and the country was on the brink of disaster. Jock left Broxburn not knowing if he would ever return. Fortunately, as we know now, the tide was about to turn in Britain’s favour. During the War, Jock served as a Sherman tank driver in the Eighth Army under Field Marshal “Monty” Montgomery. He saw action in both the North African and Italian campaigns and was rolling through Italy when Armistice was declared.

During his Army training Jock immediately stood out as a talented runner. He was soon recruited into the army cross-country team. Towards the end of his stint in the Eighth Army in Italy, he became Central Mediterranean Forces Cross-Country Champion. After the war, he was stationed in Essex awaiting his demob, which came through in 1946. That was when he met his wife-to-be, May, a Londoner. She could not be persuaded to live in Scotland so they settled in Hadleigh, Essex. There were no coal mines in Essex, so Jock went on a training course and became a qualified bricklayer. The next 30 years were spent working self-employed as a contract bricklayer. There was no shortage of construction work in and around London. Jock was always busy, and even had his own employees. Bricklaying is hard work and you have to be physically fit to do it. Despite that, Jock trained every day, sometimes running home from the building site, which could be up to 15 miles away, and then making the return journey in the morning. On Sunday early he tried to run fifteen to twenty miles so that he could have a day and a half to recover before Monday evening’s run. The weekly total was between 80 and 90 miles. “A hundred miles a week was my aim but I never quite managed it,” he admitted. Of course Jock had the usual spousal complaints about his running. Many years later, however, when his wife realised how much money could be made in events like the London Marathon, she commented that she wished Jock could have won more prizes like those!

Jock joined local club Hadleigh Olympiads in the late 1940’s. Hadleigh was a small club without track facilities. Jock therefore did all his training on the roads. Training partners included the Cook brothers, Ken and Laurie. Ken was a very good cross-country runner and ran for Essex in the Inter Counties on a few occasions. Jock started out as a cross-country runner before progressing to road running in 1950 at the suggestion of Ken Cook who had that year finished ninth in the Polytechnic Marathon. “I didn’t start running marathons right away,” he said. Like any good bricklayer, Jock began by laying down a solid foundation on the roads around his Hadleigh home. Living as he did in Essex, Jock regularly rubbed shoulders with Jim Peters, the world famous marathon runner. Jock knew Peters well and considered him a friend. “He was a brilliant runner, but he was his own worst enemy,” Jock remarked. He explained that Peters always ran flat out regardless of the conditions, and that was why he failed to finish the Empire Games Marathon of 1954. Jock also pointed out that, unlike most of his rivals, Peters included (he was an optician), he had a tough manual job and little time for training. “I was the only one doing a hard day’s work!”

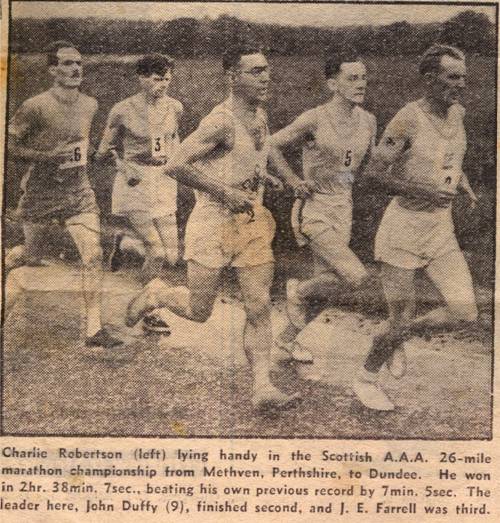

In 1951, a year after taking up marathon training, Jock made a promising long-distance running debut when he finished fifth behind winner Jim Peters in the Essex 20 in 2:00:20. A year later at Chelmsford, he improved to second place, again behind Peters, in 2:01:15. Jock made his marathon debut in the 1952 Polytechnic Marathon. The field included many of Scotland’s finest long-distance exponents, bidding for a place on the British team for the Helsinki Olympics. The business end of the race featured a terrific scrap between Jim Peters and Stan Cox, the former winning by a minute in a world record time of 2:20:42.2. With all attention on Peters, Jock went almost unnoticed as he passed the finishing post in eighth in 2:36:35. Afterwards he was delighted to receive the Lalande Trophy, awarded every year to the first newcomer to finish. After the race, Jock was introduced by an acquaintance to the other Scots who had been competing. They were Charlie Robertson (Dundee Thistle), fourth in a Scottish record of 2:30:48, Alex Kidd (Garscube) 13th in 2:38:29 and Joe McGhee (St Modan’s), 16th in 2:39:29. They all conveniently forgot to mention the upcoming Scottish marathon championship to Jock, but Jock found out anyway! Two months later he was toeing the line in Perth alongside 23 others including fellow Anglo-Scot Jack Paterson of the Polytechnic Harriers. The conditions weren’t great with a headwind all the way, but Jock was undaunted, and immediately set about stringing out the field. At 15 miles he was 23 seconds ahead of the chasing Charlie Robertson, but the Scottish record holder, competing on his home turf, was not about to give in without a fight, and sure enough he reeled Jock in. Taking the lead in the twentieth mile, Robertson opened up a winning gap on the uphill stretch to Ninewells. But just as the race looked over, barring disaster, Robertson began to struggle. At 25 miles he was in agony and taking anxious looks back. The Dundonian came to an exhausted halt almost within sight of the finishing post but when Jock was only ten yards away, he started up again, and as if magically revitalised, sprinted away to win by 100 yards in 2:38:07. Jock claimed the runner’s-up plaque, finishing 700 yards in front of Emmet Farrell (Maryhill) in 2:38:32. In those days, incidentally, SAAA plaques were only awarded to the first and second finishers. A virtual unknown within the Scottish distance running fraternity prior to this race, Jock had made quite an impact, pushing Scotland’s Number One to the limit. He had enjoyed himself greatly and vowed to come back and win the title the following year.

Jock was quickly back into training and a month later turned out for the South London Harriers 30 at Coulsdon, Surrey. It was Jock’s first “ultra”. He acquitted himself remarkably well. Finishing eighth behind winner Geoff Iden, he established an unofficial Scottish “record” of 3:17:09. He still has his finisher’s medal in the loft and vividly recalls the race: “I was running fourth with a lap to go (it was a four lap race) and half way round I thought I was doing well …. but then my legs turned like wooden sticks, and I just hobbled home,” he said, laughing.

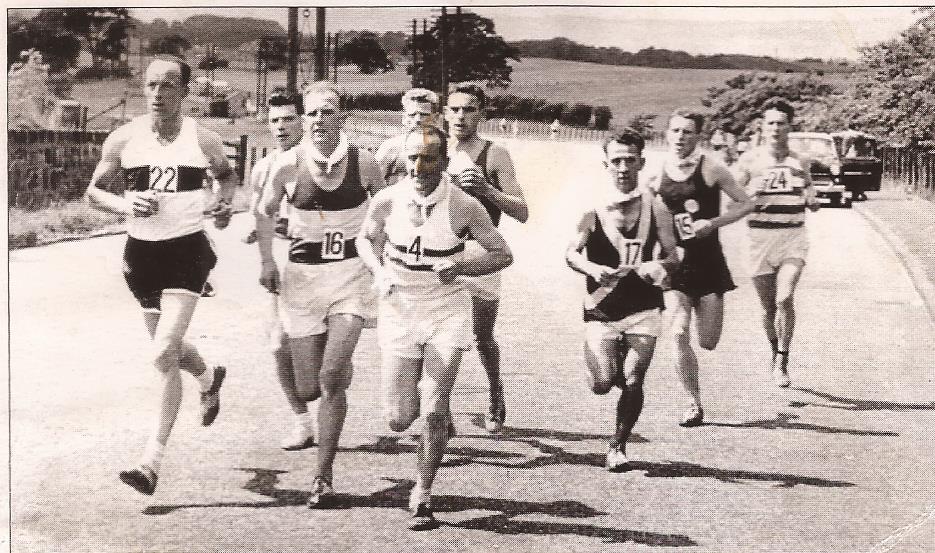

The following year (1953), Jock ran a few of the major early-season road races in the London area, finishing fifth in the Wigmore 15, 16th in the Finchley 20 (1:57:56) and winning the Essex 20 over a hilly course at Highams Park in 1L59:20. he skipped the otherwise obligatory Poly in favour of the Scottish Marathon Championship. Sadly Charlie Robertson was not running (he had retired), so Jock was unable to avenge his previous year’s defeat. The race was over the old Laurieston to New Meadowbank course, finishing during the SAAA track and field championships. It developed into an exciting scrap between Jock, Alex MacLean and Joe McGhee. MacLean took the lead at 18 miles and had 49 seconds on Jock at 20 miles. By 24 miles this had increased to 68 seconds and Jock was resigned to finishing second again. However, ‘the knock’ (Fifties equivalent of ‘the wall’) intervened and poor Alex Maclean was reduced to a walk until caught by Jock. They both ran the last mile but Jock proved stronger, winning in 2:38:00 by 43 seconds. Joe McGhee showed obvious potential by finishing faster than the others and was only 62 seconds down on the winner. Again quoting ‘A Hardy Race’ , Jock “had shown real guts in running himself out to the tape and he fully deserved his championship victory.”

On the eve of the race, Jock, his wife and two daughters had taken the train from Southend to London, and then the “Starlight Express” to Scotland – a twelve hour journey. Reaching Broxburn at 3:00 am, he had snatched a few hours sleep before his father arranged for an ex-Hibernian player to give him a rub-down. Then it was off to Falkirk for the marathon start. Dunky Wright apparently wrote in the newspaper that “Duffy always looked tired.” No wonder! He remembers Alex MacLean’s drive for victory, but although the gap widened he just kept on trying hard until he could see the leader struggling, and caught him with a mile to go. Sportingly, Alex said “Good luck to you, mate” as Jock went past. Jock’s parents and brothers were waiting in Meadowbank Stadium when it was announced that Alex MacLean was about to win the marathon – and then Jock came in, triumphant.

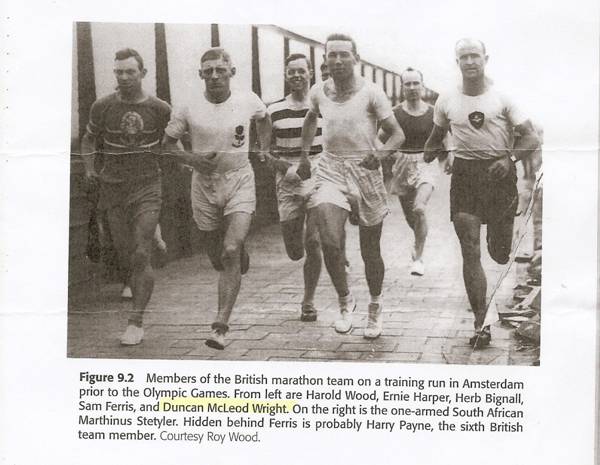

Jock first crossed paths with Dunky Wright in 1952. Wright as President of the Scottish Marathon Club was the SAAA Officer in charge of the marathon. “He didn’t like me,” was all Jock had to say about the former Empire Games marathon champion. Being the reigning Scottish champion, Jock had high hopes of being selected for the 1954 Empire Games in Vancouver, Canada. Early in 1954, he underpinned his ambitions by running a fast 15-miler in 1:23:52. But Jock was disappointed when, even before the Scottish Marathon Championship, only Joe McGhee , whom he had beaten three times over the classic distance, was nominated. Jim Peters even wrote to the SAAA on behalf of the 1953 champion, but to no avail. Nevertheless Jock entered the 1954 Scottish Championship in the hope of impressing the SAAA committee and clinching selection. Though pre-selected, Joe McGhee was also among the entries. The course was a new one from the Cloch Lighthouse in Greenock to Ibrox Park where the Glasgow Highland Games were being held. Before the race, Jock was taken aside by Wright and informed that if he was not satisfied with the result, Jock would have to run again in the Polytechnic Marathon! Sending athletes to Vancouver was an expensive business, so Jock needed a truly impressive performance to impress the SAAA committee. However there was no chance of that. It was very warm and there was a stiff headwind blowing. The time at 5 miles after a fast start was 27:11 with Jock, McGhee, Hamilton Lawrence of Teviotdale Harriers and George King of Wellpark Harriers all together. After 15 miles and the long hill up from Langbank, Joe McGhee took the lead and kept up a fast pace into the wind. While no fewer than 18 of the 25 starters were forced to drop out, Joe McGhee ran on as though closely pursued and won by eight minutes in an excellent championship record of 2:35:22. By running such an excellent time in unfavourable conditions, the quiet spoken McGhee had not only vindicated his nomination, but also shown he was capable of much greater things. Fighting a losing battle against the wind and heat, with nothing to run for, Jock dropped out at 17 miles. He duly entered the Poly four weeks later but did not finish. Thus Joe McGhee would be Scotland’s sole representative in the ’54 Empire Games marathon. Rather a shame for Scotland, because Jock, who knew his English rivals so well, reckoned he had a chance of third place in Vancouver, although he did not drink water either in training or in a marathon, unless he was having a bad time. The story of the Empire Games marathon needs little further elaboration here. Unfortunately the race is notorious rather than famous – and for the sight of poor Jim Peters, badly affected by sunstroke and his own headstrong pace, staggering and collapsing short of the finish. Yet the statistics prove that the winner and gold medallist was Joe McGhee of Scotland in 2:39:36 from South African Jackie Mekler, the famous ultra runner in 2:40:57 with Johannes Barnard, also of South Africa, in 2:51:49. There were only six finishers. With the benefit of hindsight, the SAAA may well have selected Jock but who then could have foreseen that 2:51 would be good enough for a medal?

Jock’s 1955 season was a quiet one in the aftermath of his non-selection for the Empire Games. His best results that year were a fifth place finish in the Essex 20 (2:01:28) and twenty second in the Poly (2:44:15). That performance ranked him fifth in Scotland that year – a year dominated by Joe McGhee who romped away with the Scottish championship in 2:25:50. The next season marked a return to form for Jock and, finishing third in the Southern 20 in 1:56:51 he became an Essex champion for the first time. He was doubly rewarded with a Hadleigh team victory. The Poly turned out to be a very fast race, and Jock, after starting quickly, slumped to thirty sixth in 2:39:58.

After that, Jock stopped competing for about a year. He returned to the fray in the Spring of 1958 when he finished fifth in the Essex 20 (1:58:33) after flying through the first ten in 55:28. By June he was in such good form that he decided to enter the Scottish Marathon Championship again. However he came unstuck when he addressed his entry form to the wrong person. After making the long journey north, Jock arrived in Falkirk only to find that his name was not on the entry list, and that he would not be allowed to run. It was at about this time that Jock, who was now in his late thirties, resolved to hang up his racing shoes for good. Hadleigh Olympiads kept going for several years but remained a small club. American runner Buddy Edelen put Hadleigh on the map in the early 1960’s whilst on a teaching stint in Britain. He is best remembered for winning the 1963 Polytechnic Marathon in a world record of 2:14:28.

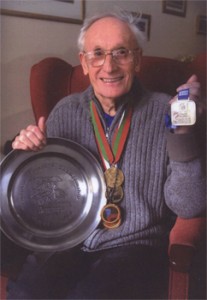

After retirement Jock, at the express wish of his late wife, returned to his native Broxburn. Today he lives in a sheltered housing development. Jock is 91 now which makes him Scotland’s oldest living marathon champion!

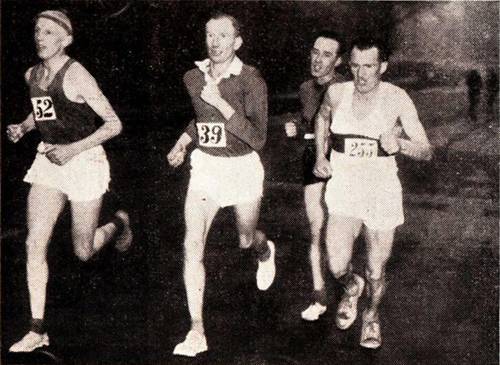

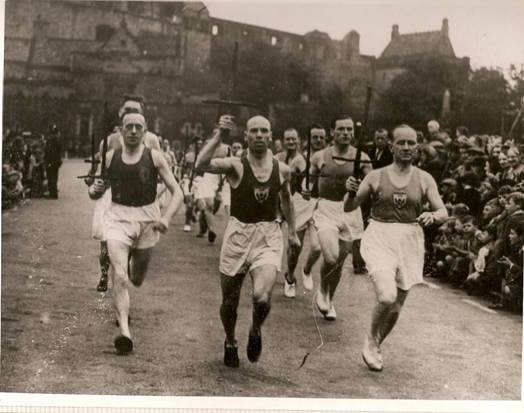

Jock (255) Running in the 1954 Mitcham 15 Miles

After reading Alex’s profile of Jock, I think that most people interested in marathon running will feel that a gap in their knowledge has been filled and will be grateful to Alex for telling the story of a remarkable athlete.