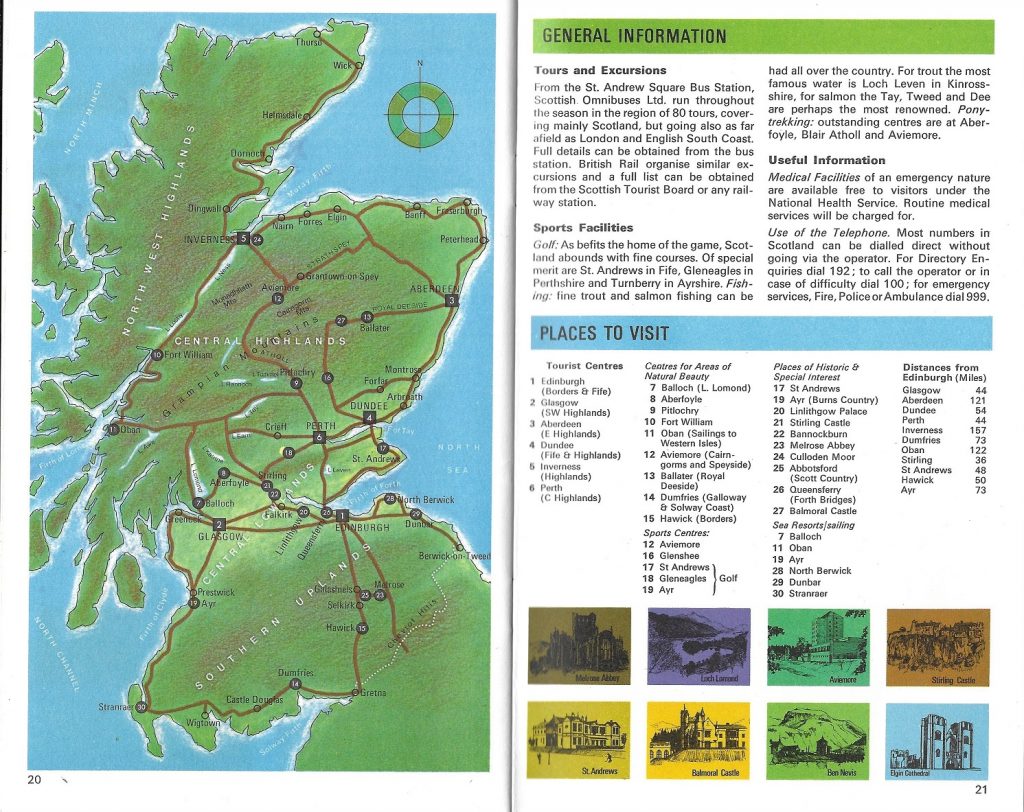

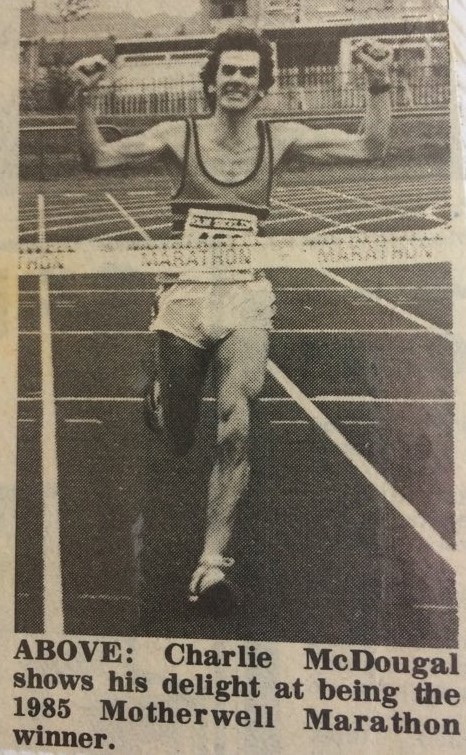

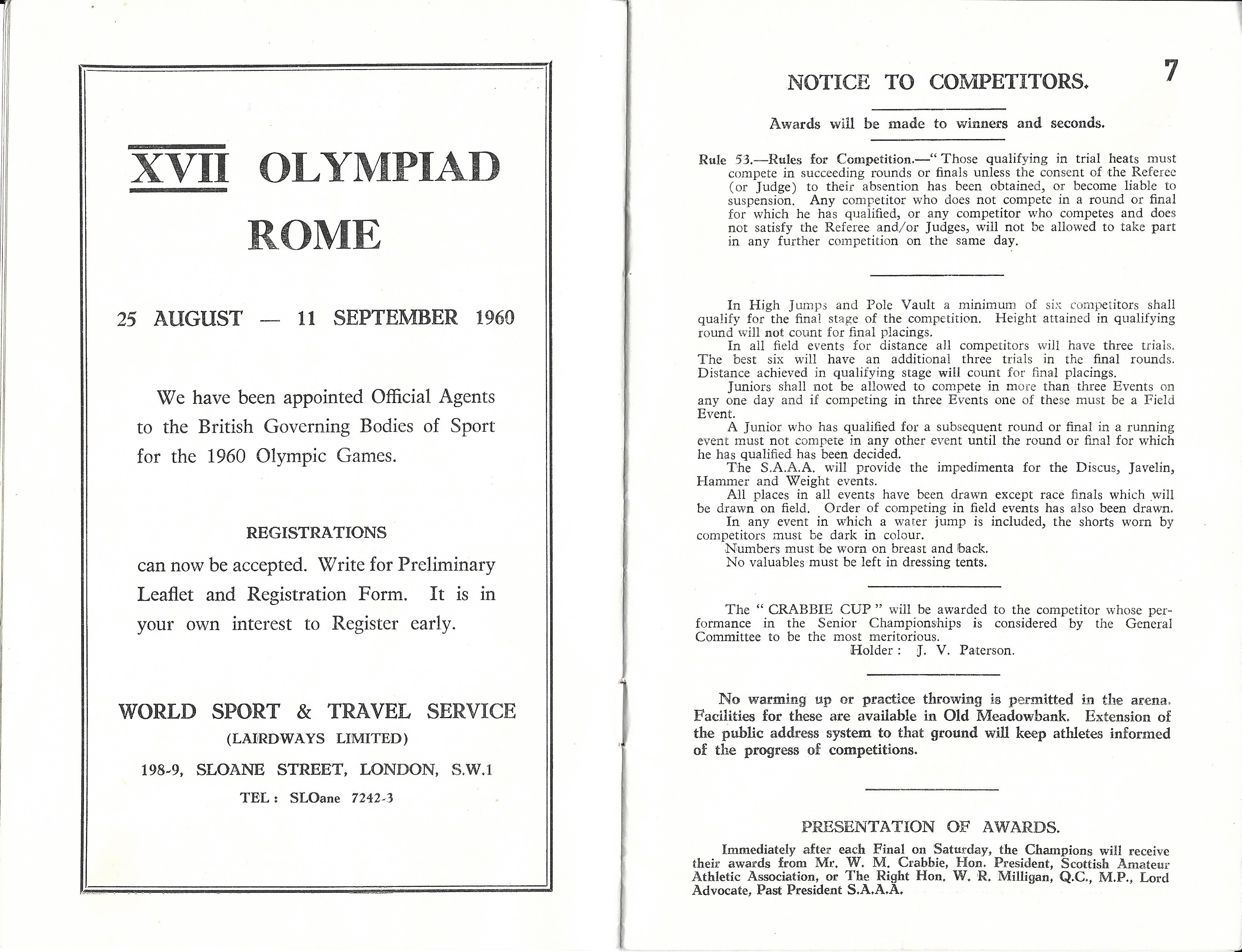

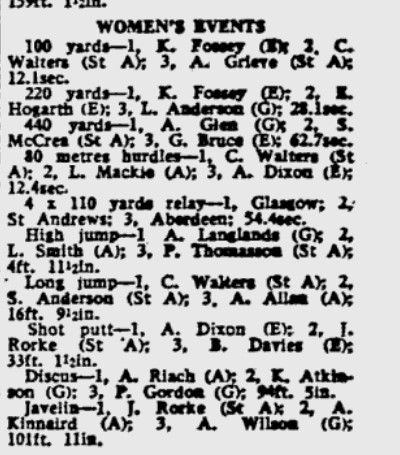

Sandy Sutherland modelling the light blue blazer

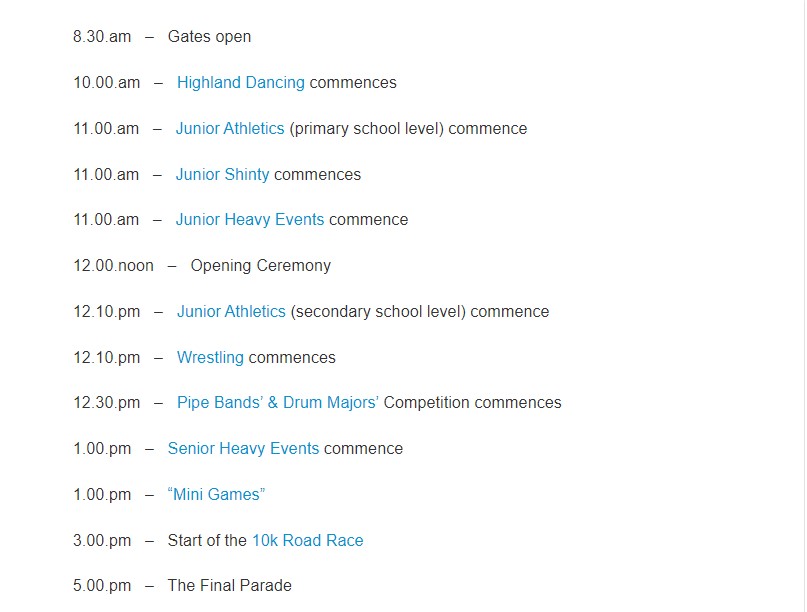

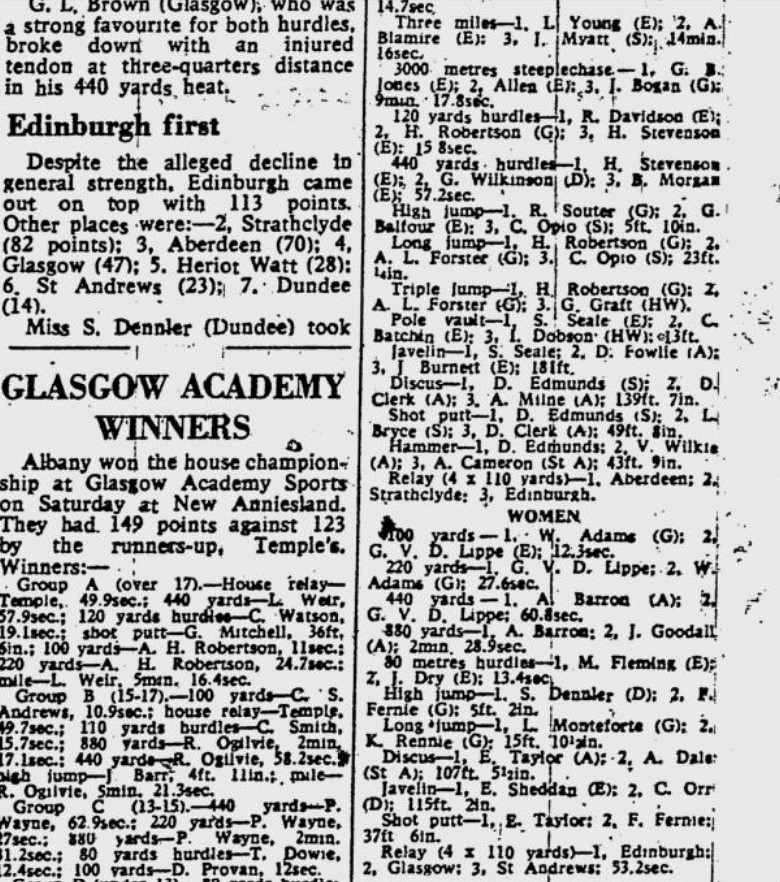

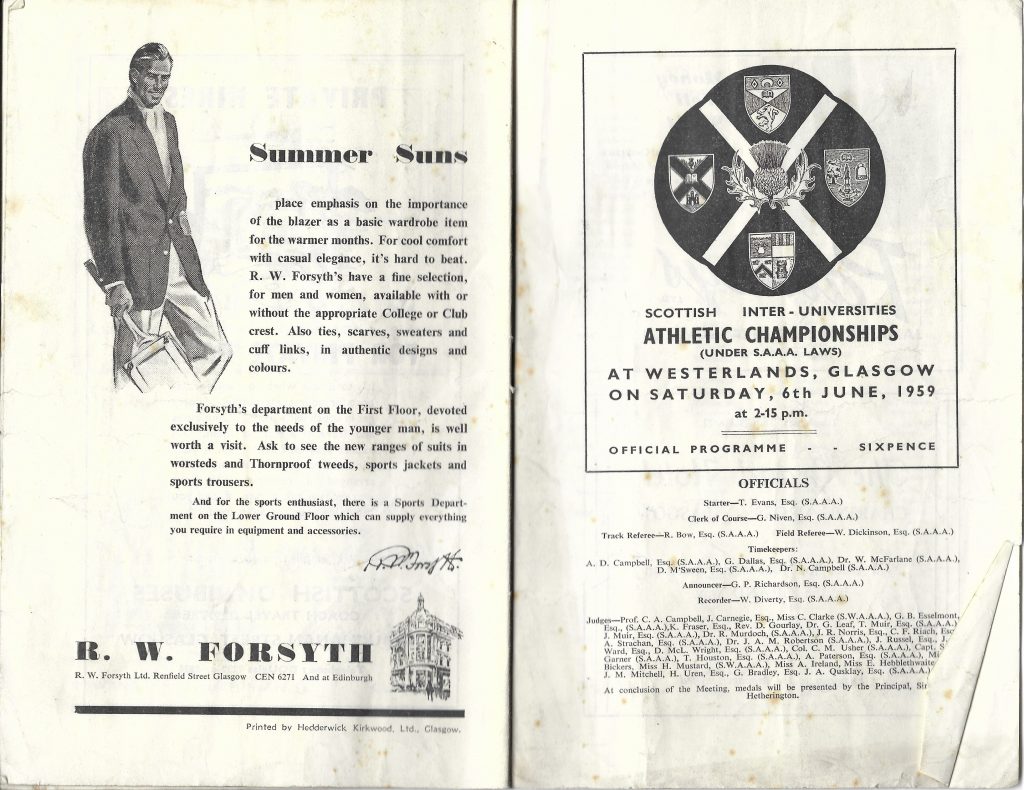

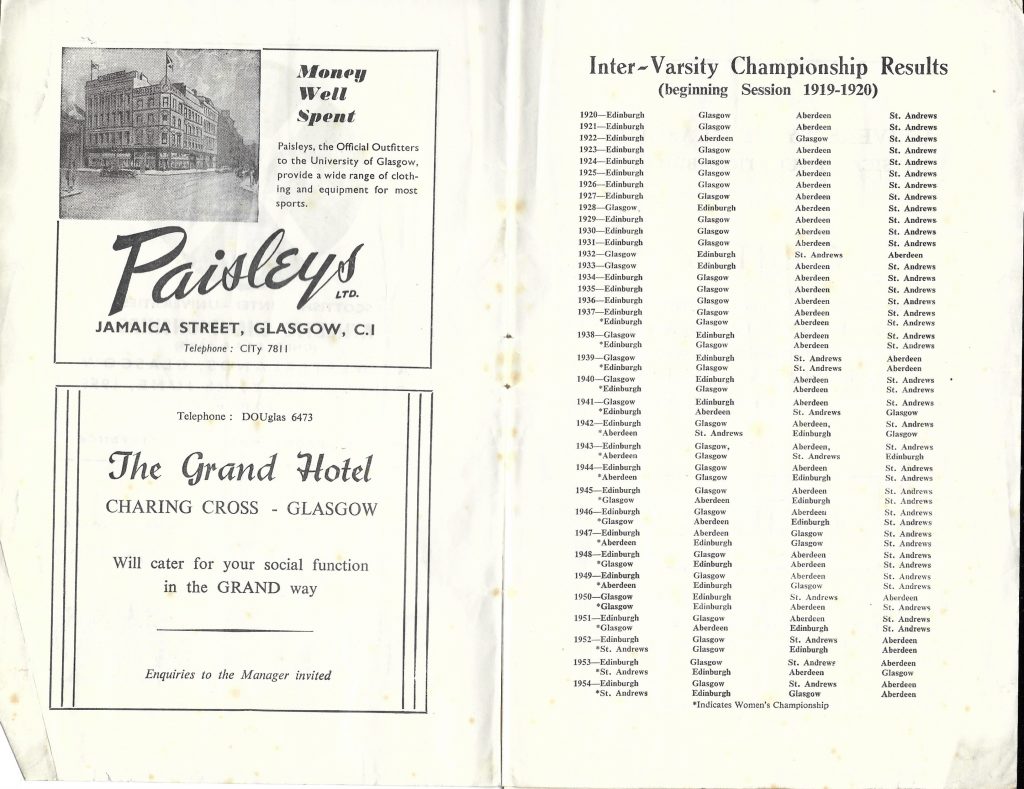

Being awarded a Blue for your sport at University was a very high honour indeed with very few being awarded each year. Wikipedia comments that “A blue is an award of sporting colours earned by athletes at some universities and schools for competition at the highest level. The awarding of blues began at Oxford and Cambridge universities in England.” All sports which represented the University were able to award a Blue. The practice was almost immediately adopted by all four of the “ancient” universities of Scotland it is a signal award for any sportsman. Usually awarded for general excellence in the chosen sport over a period, very few are awarded in any one year. eg in Glasgow there was one awarded by the Hares & Hounds in 1962-63 (Allan Faulds) and then one awarded in 1964-65 (Brian Scobie). Former GU H&H secretary John McCall tells us that “A Blue was awarded , eg for being Scottish university champion, running in British university championships etc. Jim Bogan, Doug Gifford, Brian Scobie, Allan Faulds, Calum Laing etc were all blues. I think Hares and Hounds would nominate to GUAC.”

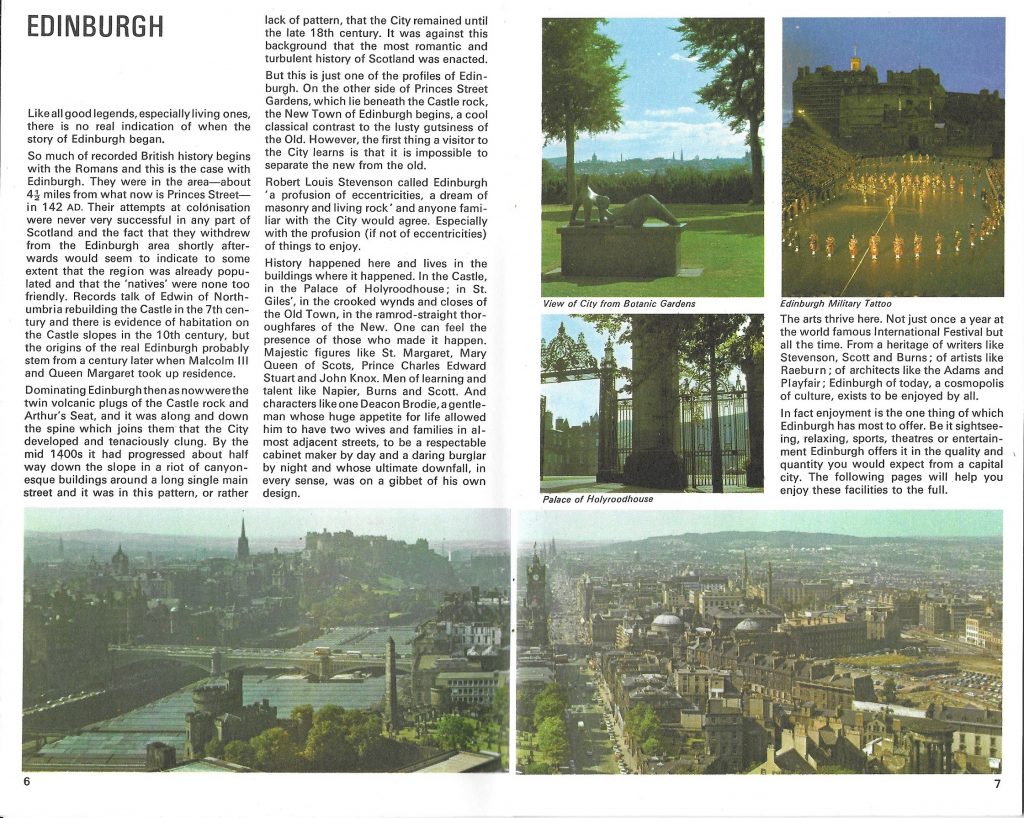

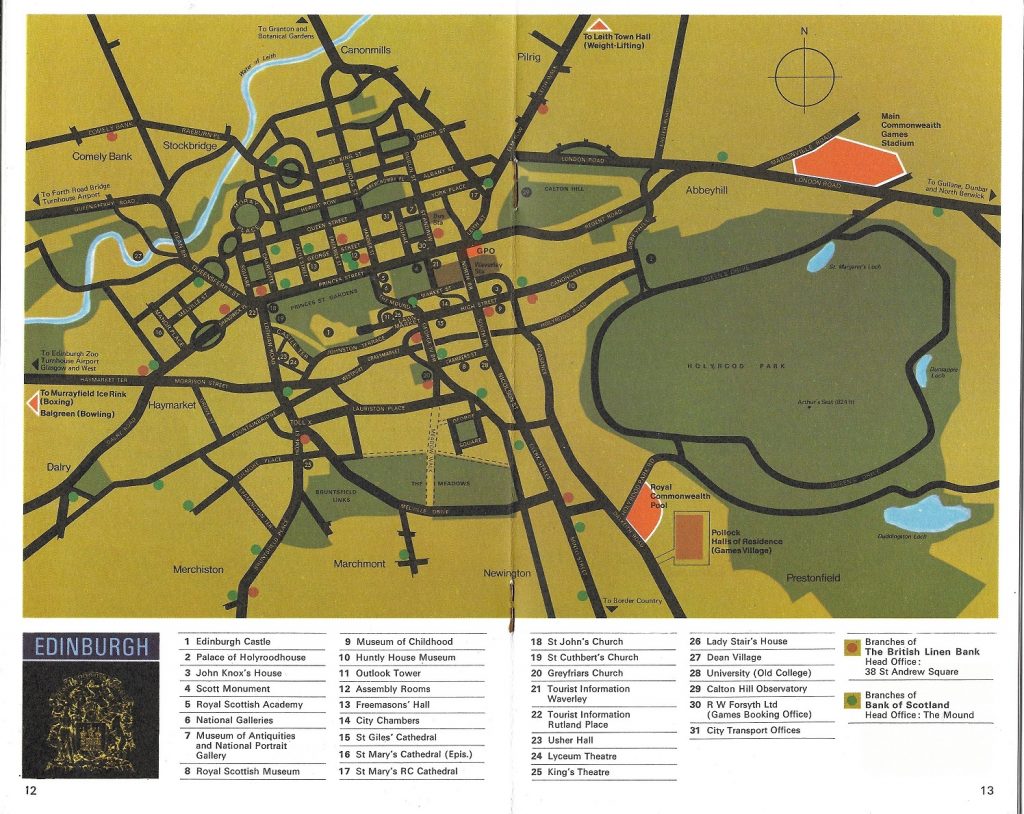

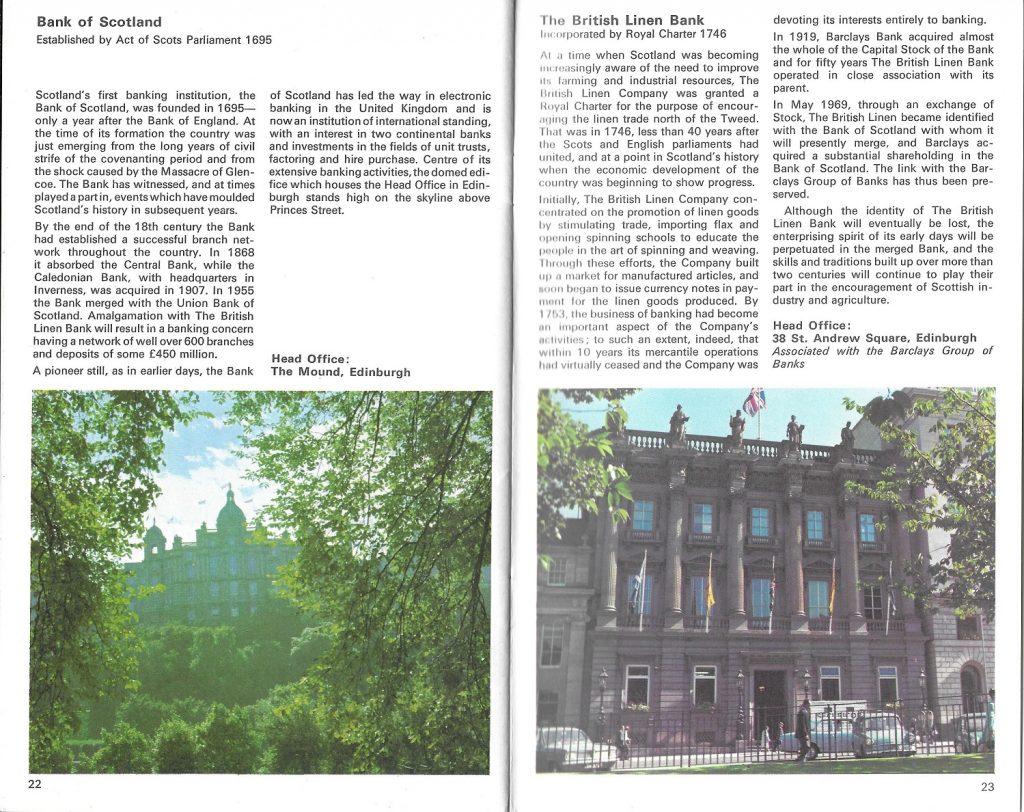

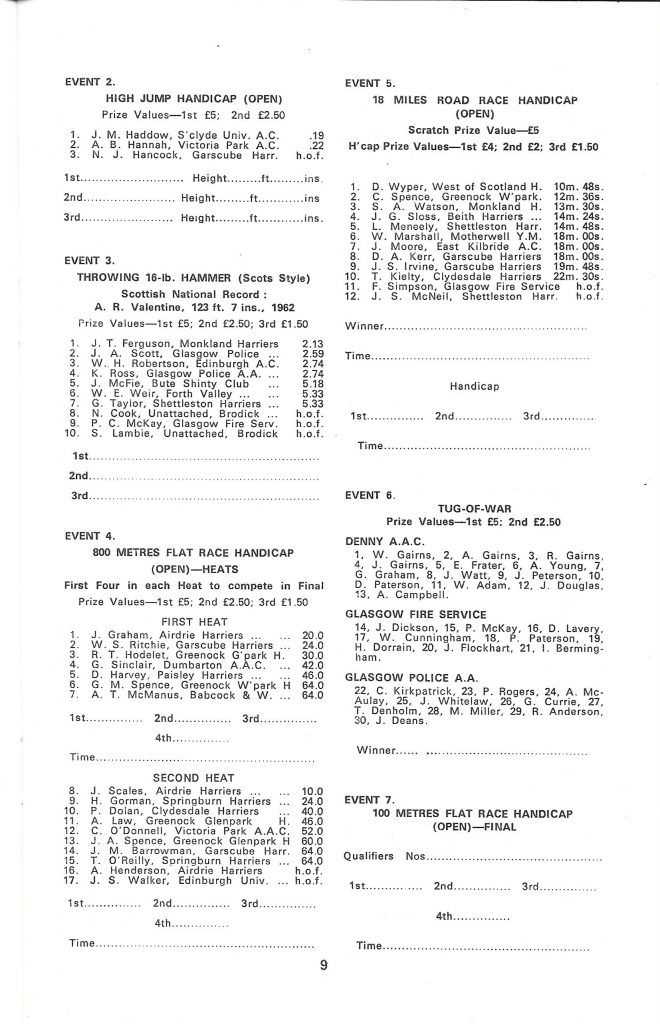

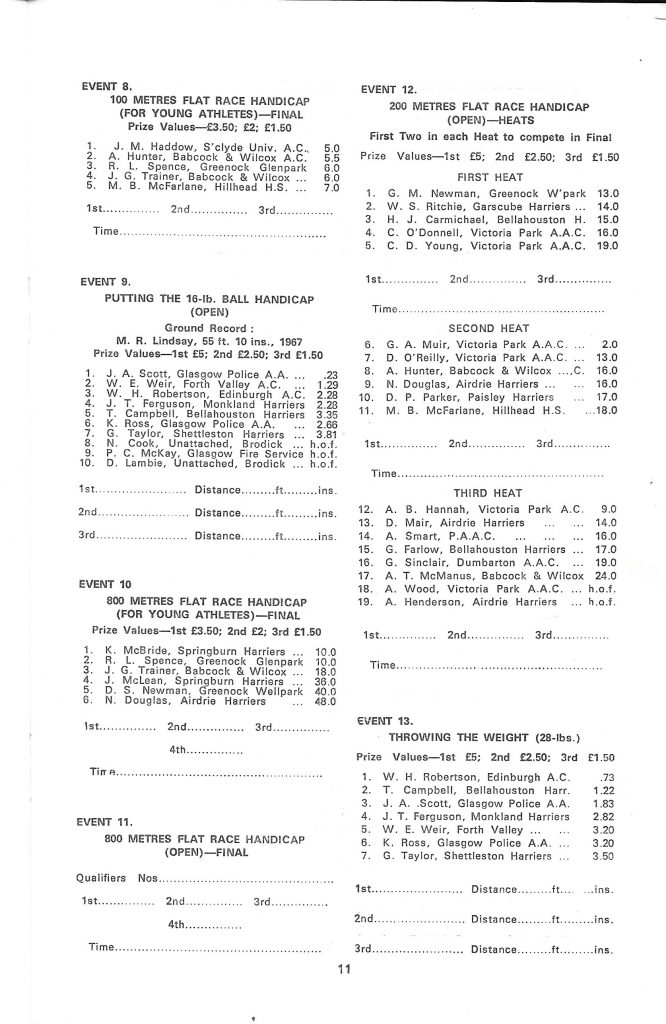

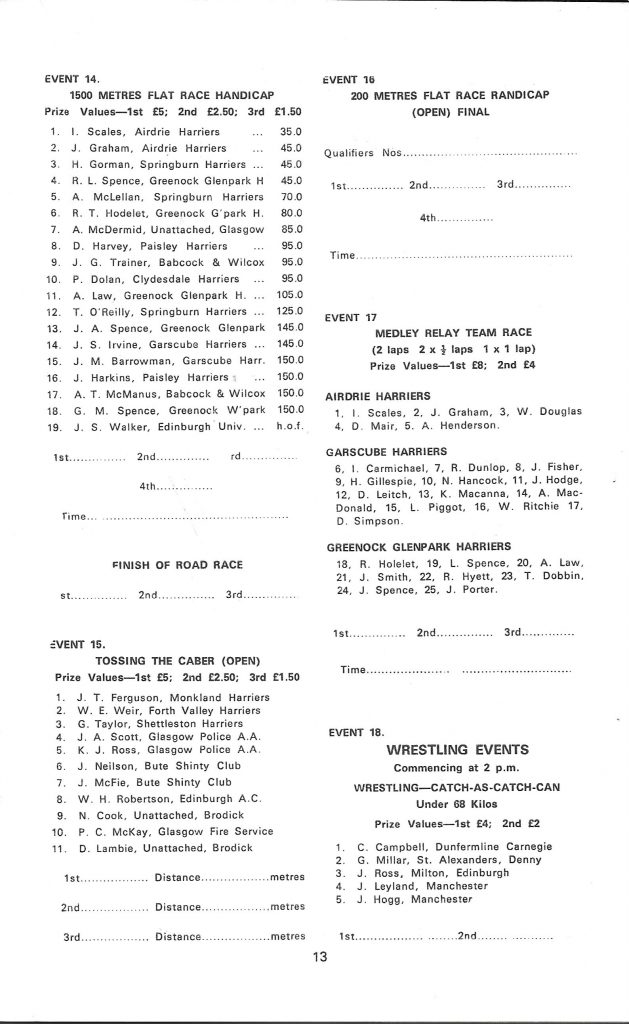

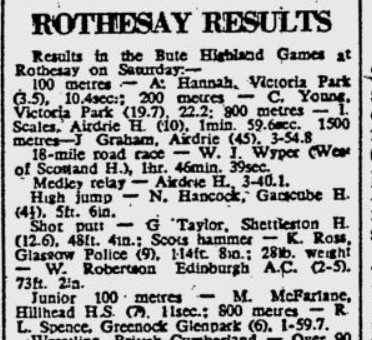

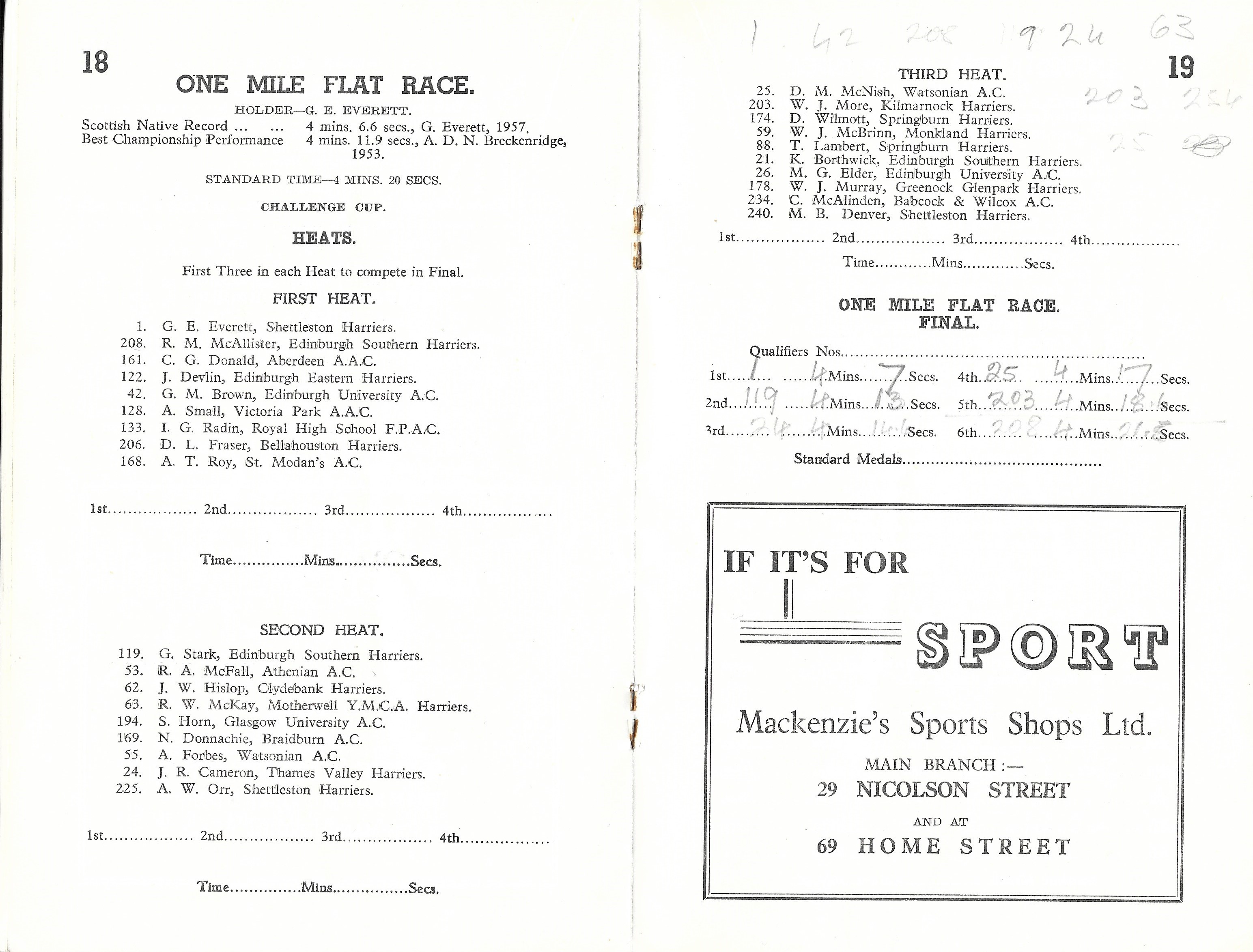

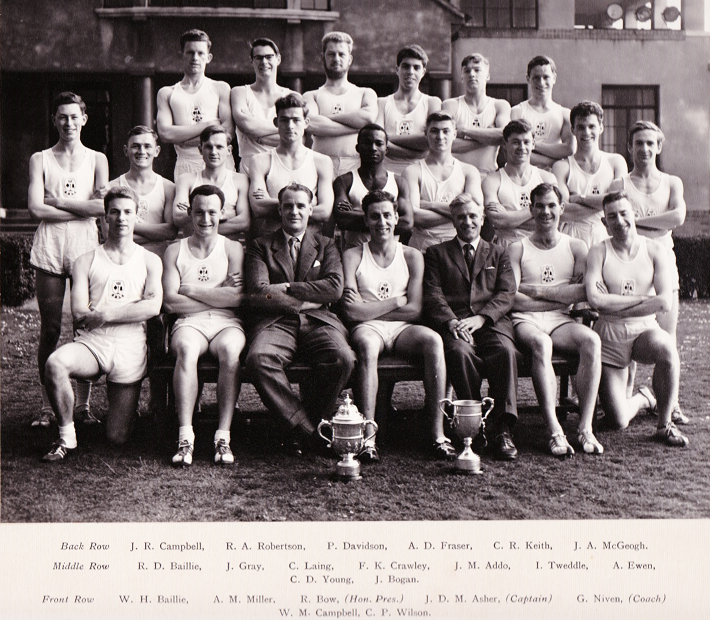

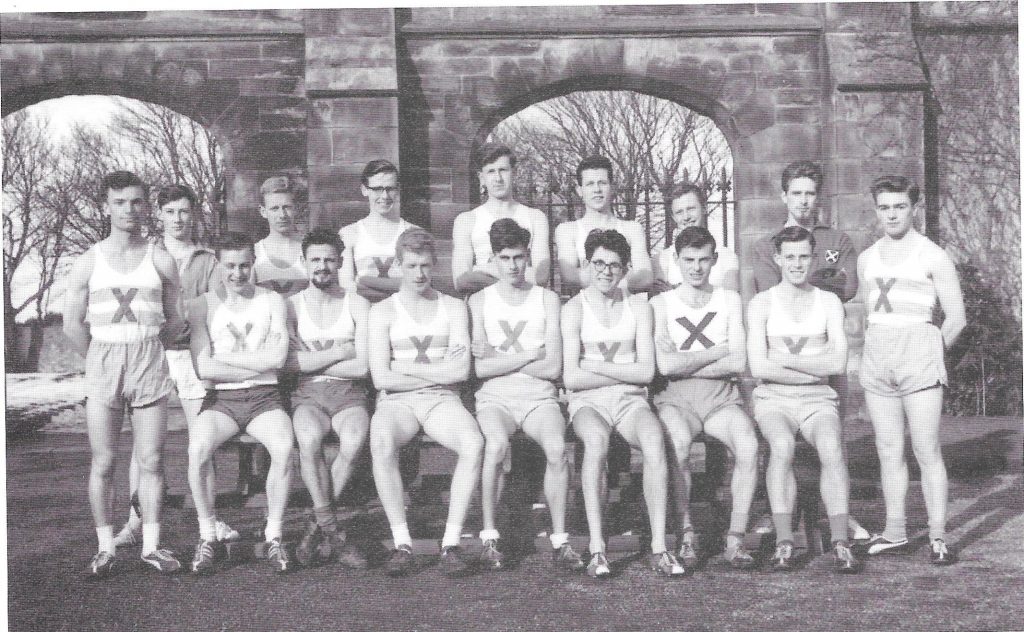

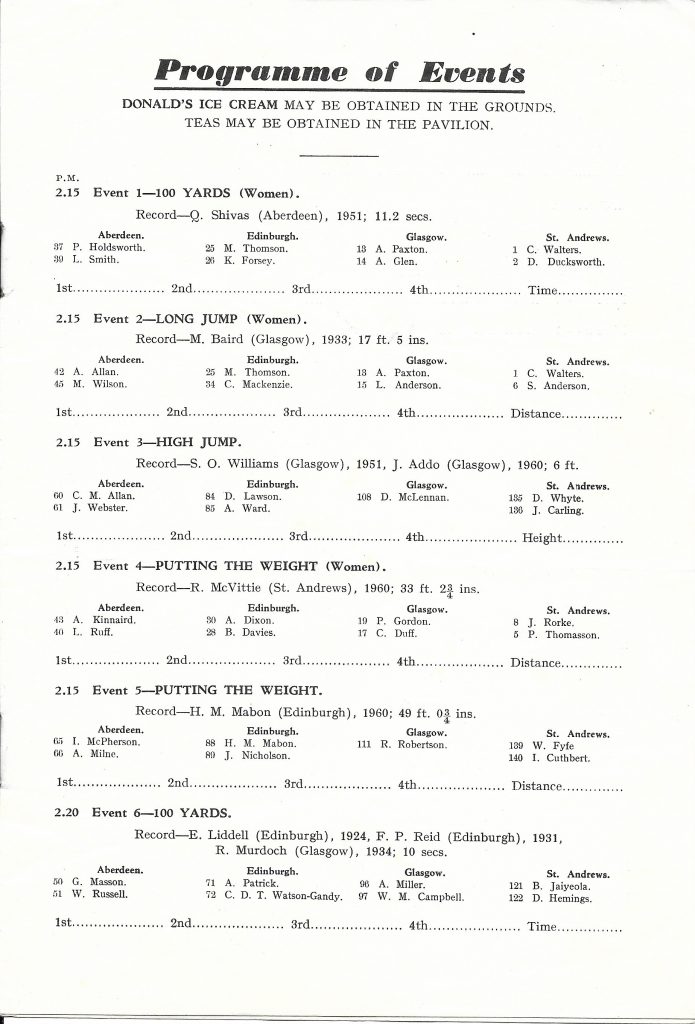

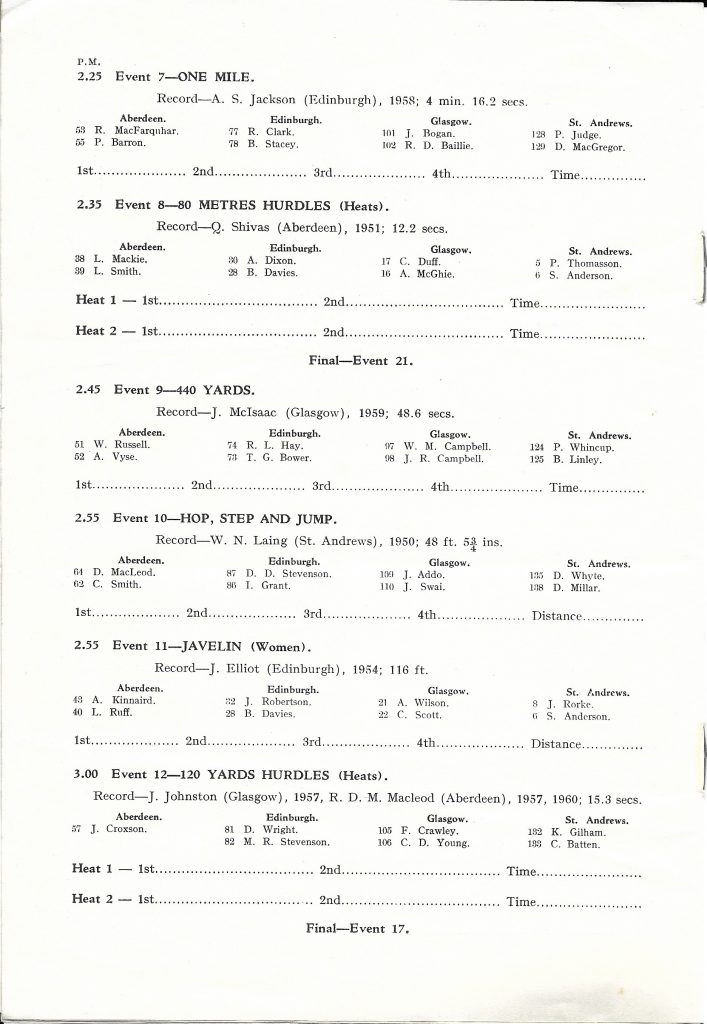

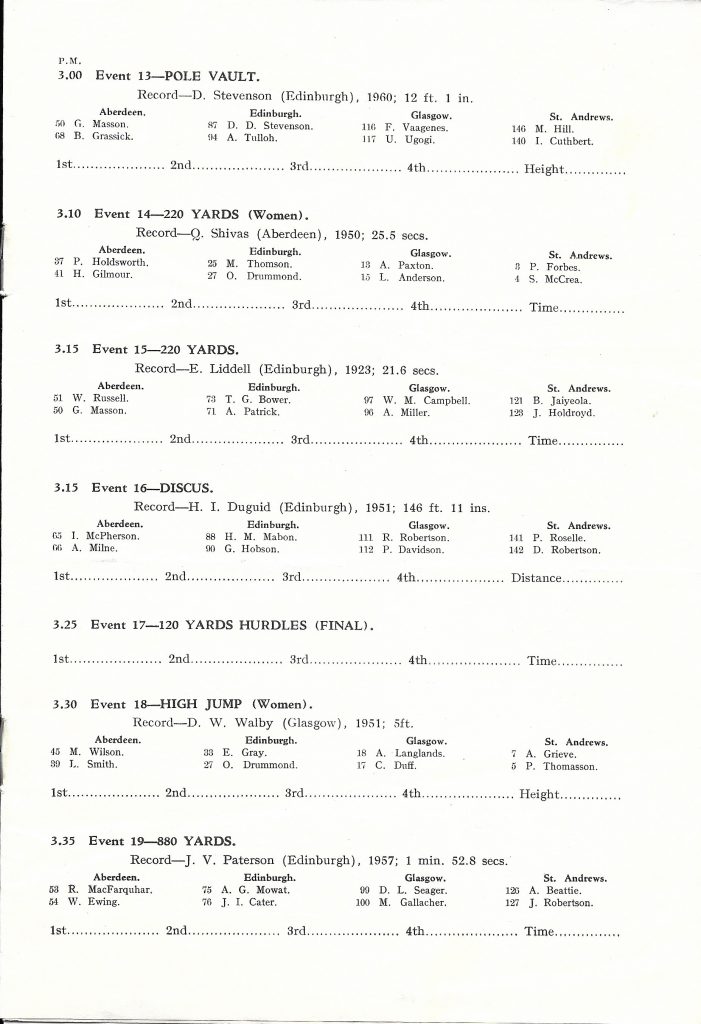

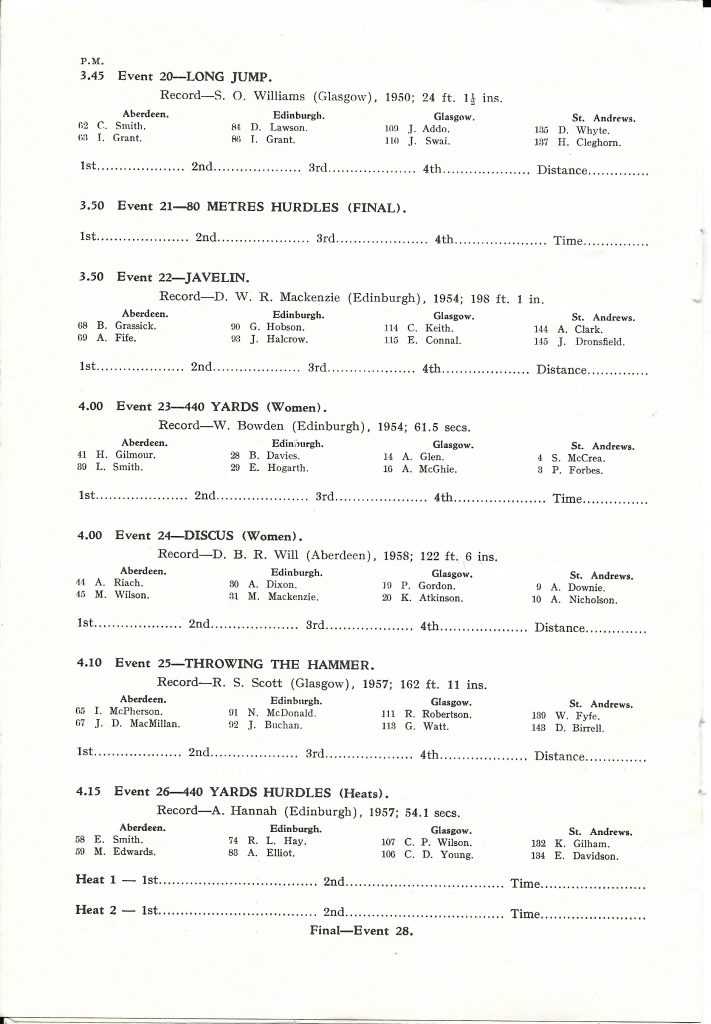

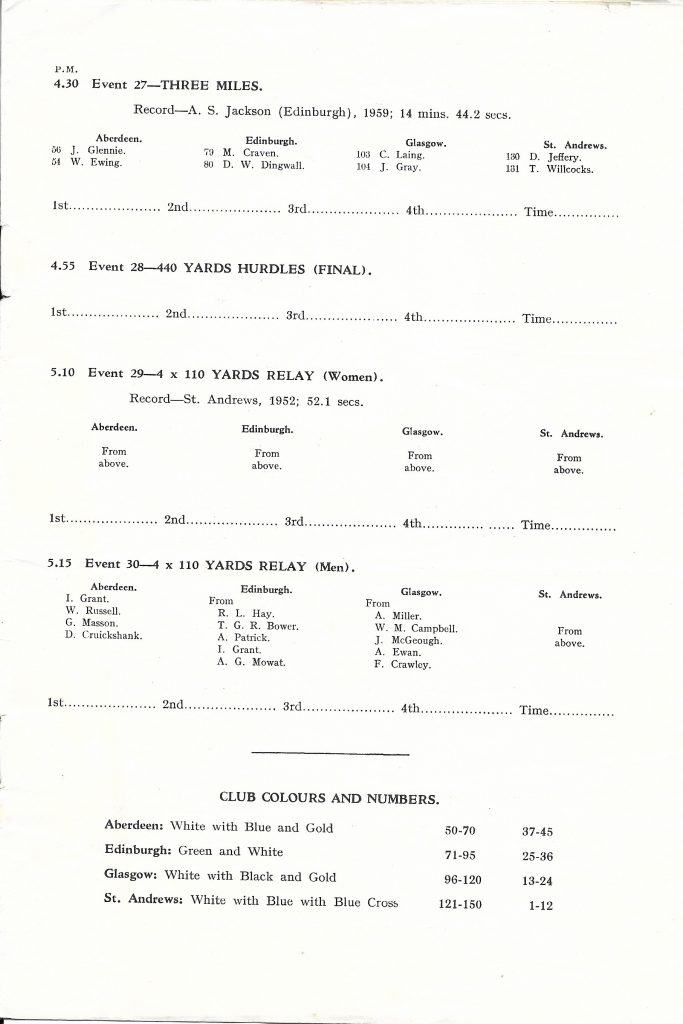

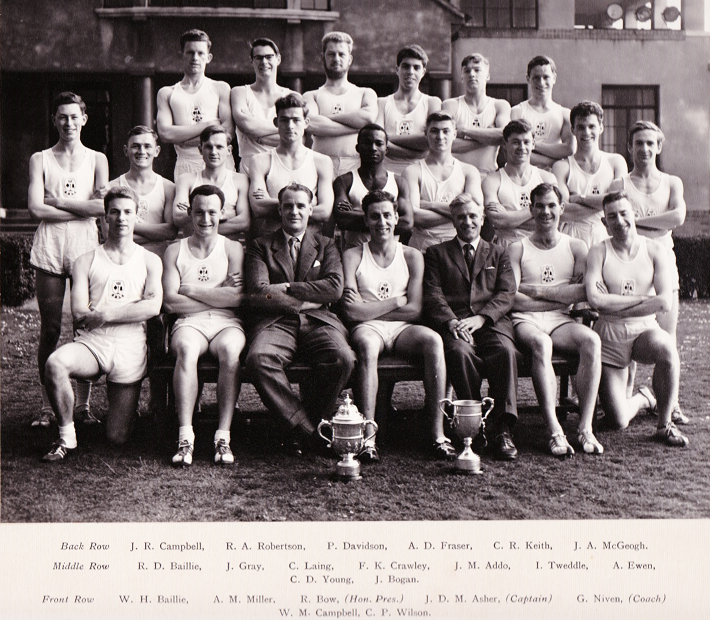

The GUAC team from the early 1960’s with several blues included – notably WM Campbell, C Laing, J Bogan and RD Baillie

The road to the Blue went through another vetting Sandy Sutherland (a double blue himself – athletics and weight-lifting – was President of the GUAC and at one time in the 1960’s chaired the Blues Committee. He had signed the certificates when he was Secretary. He says: “In my day the main criterion was that you had to have represented Scottish Universities or better – a full internationalist would almost certainly be awarded a full BLUE but forms had to be filled in and the club committee had to propose and second him or her.” On the question of whether an athlete could receive a Blue for the same sport in more than one year, he was quite clear – “at Glasgow University once a Blue always a Blue and you were eligible to wear the Blue apparel – in the past there may well have been additional stripes or colours or whatever! But if you succeeded in a different sport then you could become a DOUBLE Blue as I was in athletics (track & field) and weight-lifting.” So – not possible to get a Blue a year with added bars or dates to the blazer at Glasgow University.

This was corroborated by Douglas MacDonald who was on the committee 20 years later. He says: “My first spell on the blues committee was in my role as GUAC president in the early 80s. As far as I can remember, the process was that the different GUAC clubs nominated candidates for Blues to the Blues committee who considered the supporting material prior to awards being made at the annual Blues dinner. At this dinner, the prize for best club and best sports individual was also made. The Blue was awarded for one season only: not for achievements over a student’s university year. I don’t remember many clubs nominating athletes for half blues but it was within the power of the blues committee to award this if they hadn’t been fully persuaded by the club’s presentation. He went on to say that “There were no formal guidelines for Blues nominations so the committee was often faced to make impossible comparisons between sports in trying to establish comparable merit. The situation was made more difficult by some clubs whose committees thought that speculative nominations were legitimate (inflated claims of merit, etc.) ” There will be some comments about the difficulties faced by the committee at the end of this article.

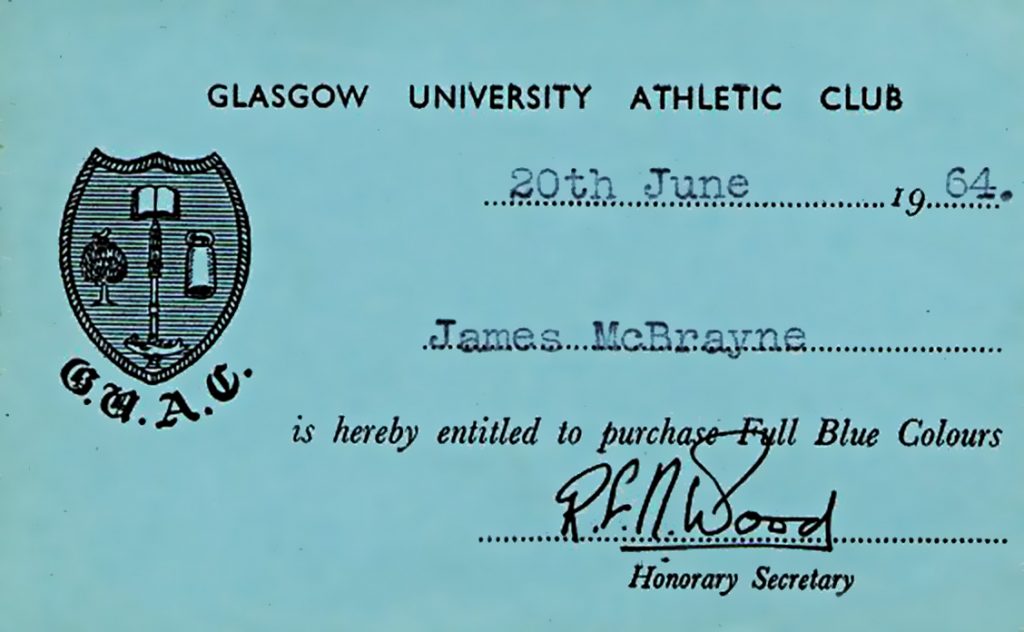

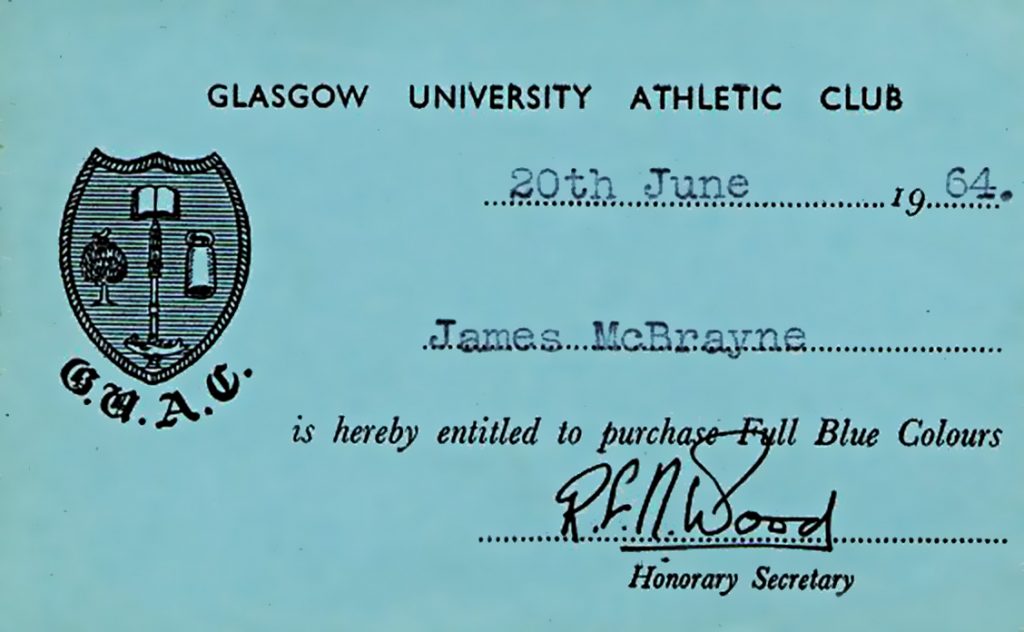

The card above was awarded to international diver and British Champion James McBrayne at Glasgow. In 1964 McBrayne had been second in the British Universities Springboard Championship but in 1965 he won the Scottish Springboard and Highboard Championships, and the British Universities Springboard with a third place in the Highboard. Superb achievements.

The athlete was usually allowed to buy blazer and tie, with the appropriate insignia. Most bought the tie but were reluctant to splash out on a blazer – especially if the award was in the final or even penultimate year. Once the announcement of the award was made, the athlete was given the accreditation to purchase the relevant items. The Glasgow Blues tie is shown below, and Sandy Sutherland models the blazer at the top of the page.

Douglas MacDonald refers above to the annual Blues Dinner. This was more than just an annual club knees-up as Wikipedia says “The Glasgow University Sports Association provides financial, administrative and representational support to individuals and groups involved in sport and recreation at University of Glasgow. There are currently over 40 clubs affiliated to the Association. The highlight of the Association’s year is the GUSA Ball (or Annual Awards Dinner and Dance) in February, a black-tie affair at which Blues, Half-Blues and Awards are presented to successful athletes and teams. “

One former Blue said apologetically that he was a bit obsessive-compulsive and had kept all his stuff. He was sorry that he couldn’t afford the blazer but he had everything else. There was no need for him to be apologetic – it was an honour awarded at a time when University sports were respected and highly regarded at national level, and the chosen sport could be indulged in freely and with great pleasure. Many former Blues keep the precious awards safely tucked away after leaving their alma mater.

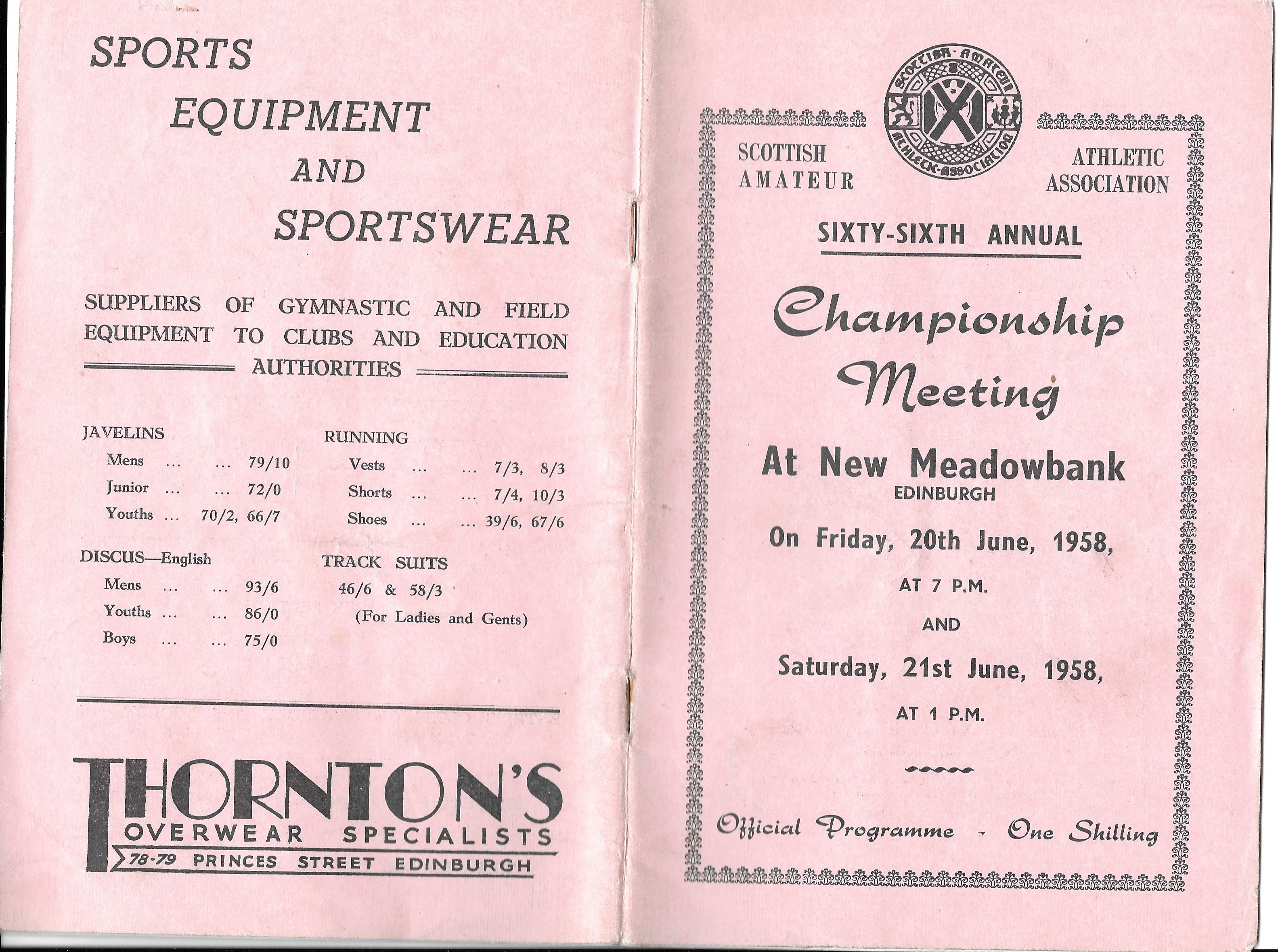

It was also a matter for debate which sports could award Blues – not all sports were equal in the eyes of sportsmen. We obtained some extracts from the Glasgow University Athletic Club Committee and the first comments refer to this aspect. A range of sports are mentioned here in the context of Blues being awarded.

11/12/56 GU basketball applied for Full Blue status.

28/1/57 Basketball was awarded Full Blue status by GUAC

11/3/58 John Asher well known and popular member of the GU athletics community was awarded a Shinty BLUE.

Basketball Full Blues were awarded to D.M McKinnon and W Warden

10/6/58 A Half Blue for Basketball was awarded to Norma Fraser who had toured with the Scottish Ladies Team.

10/2/59 Mr J. Gilroy was invited to join the GUAC Blues Committee

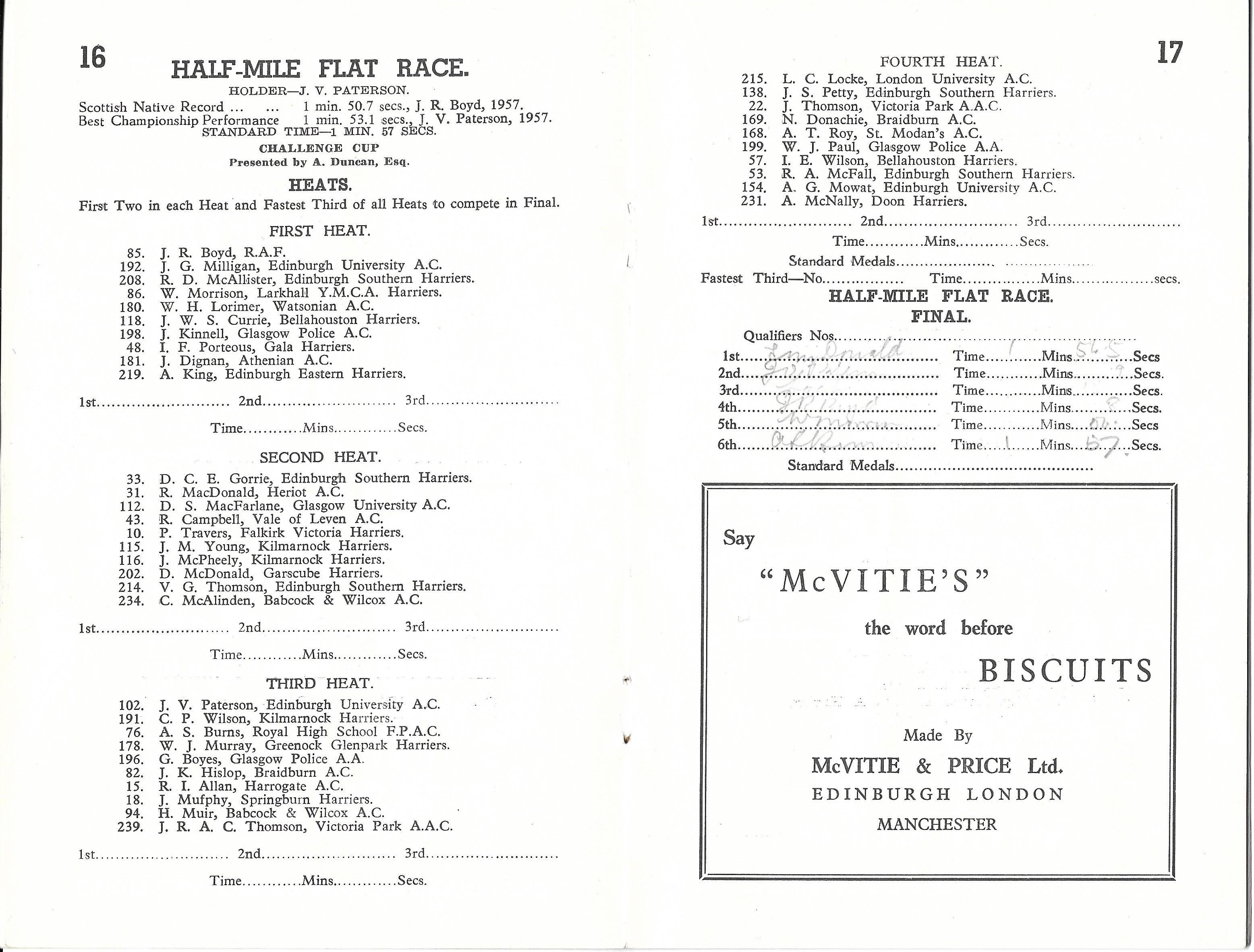

3/3/59 Jim Bogan was awarded a Cross Country Blue as were Stan Horn and Eileen Wilson for hockey.

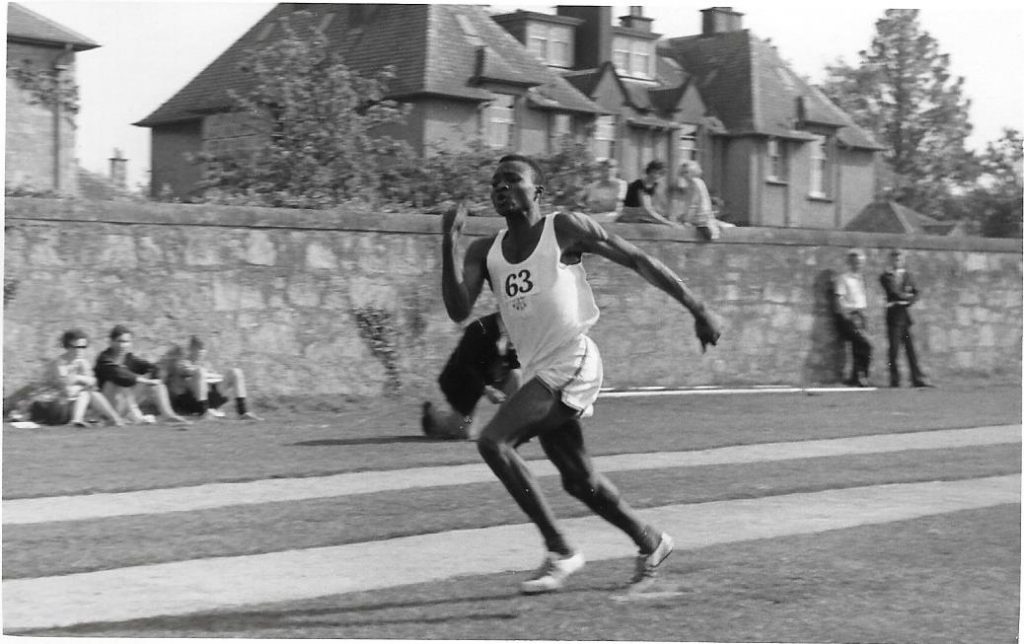

9/6/59 Ann Glen awarded a Full Blue for athletics.

Colin Keith (javelin), Bobby Mills (440 hurdles) John Addo (long and triple jumps), W.R Galbraith, John C Swai and Miss L Williams also awarded Full Blues.

14/6/60 a second Full Blue was awarded to Ann Glen in Basketball

13/6/61 Athletics Full Blues awarded to Ming Campbell, Frank Crawley (high hurdles), Calum Laing, Alison Langlands,

12/6/62 Full Blues in athletics awarded to Ray Bailiie (880y one mile) Jim Tynan (javelin), and A.L.Sutherland!

Athletics, Basketball, Hockey, Cross-Country and Shinty were all there. There is also reference to the Blues Committee as well as the need for recognition to go through the Committee before any sport could award a Blue.

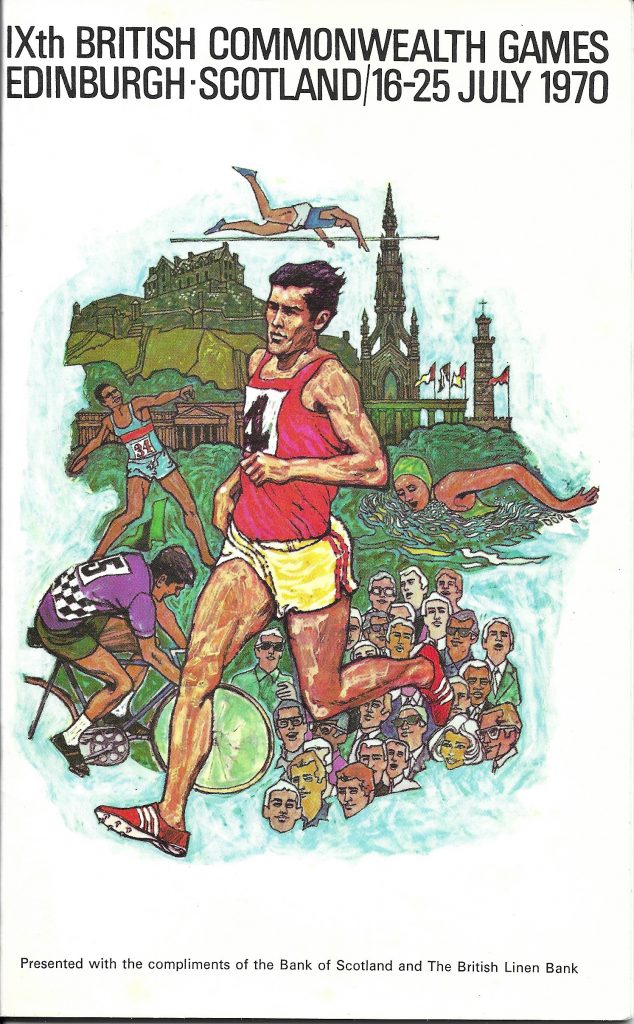

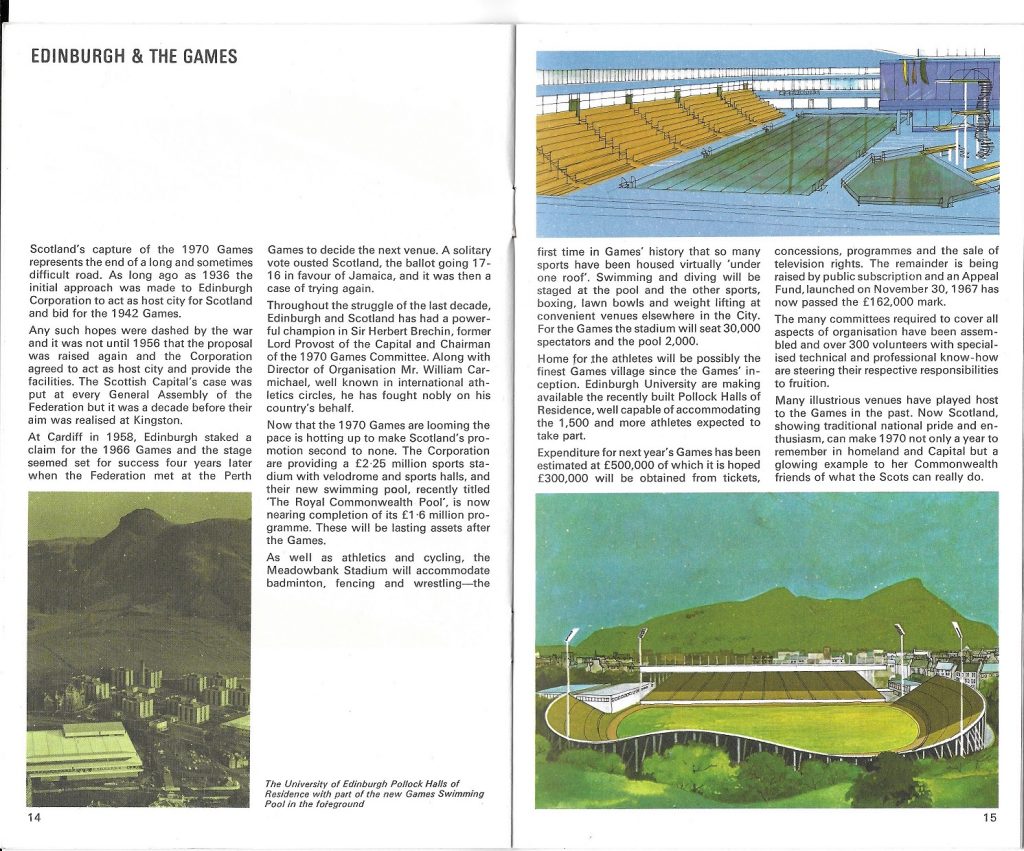

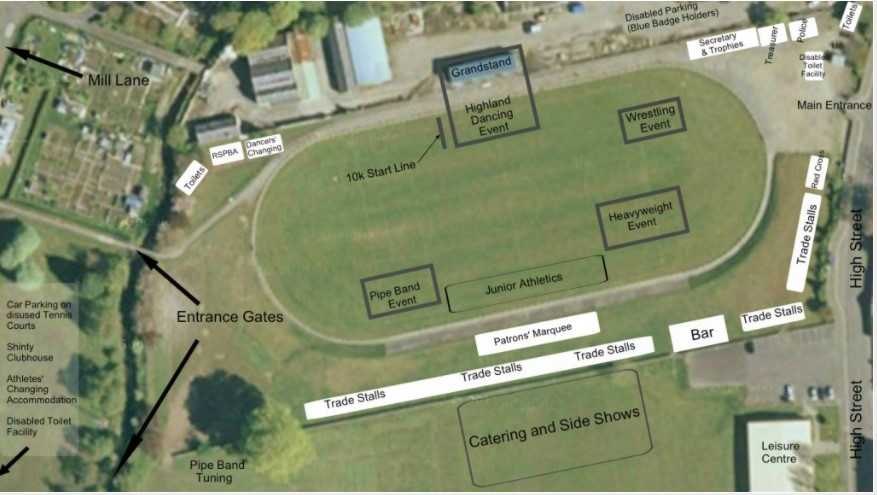

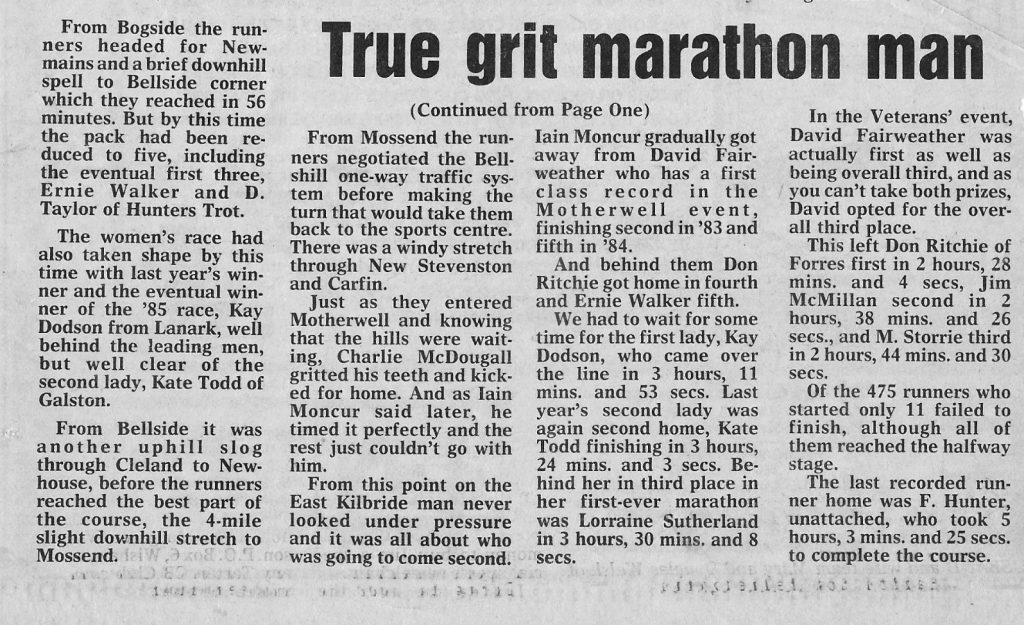

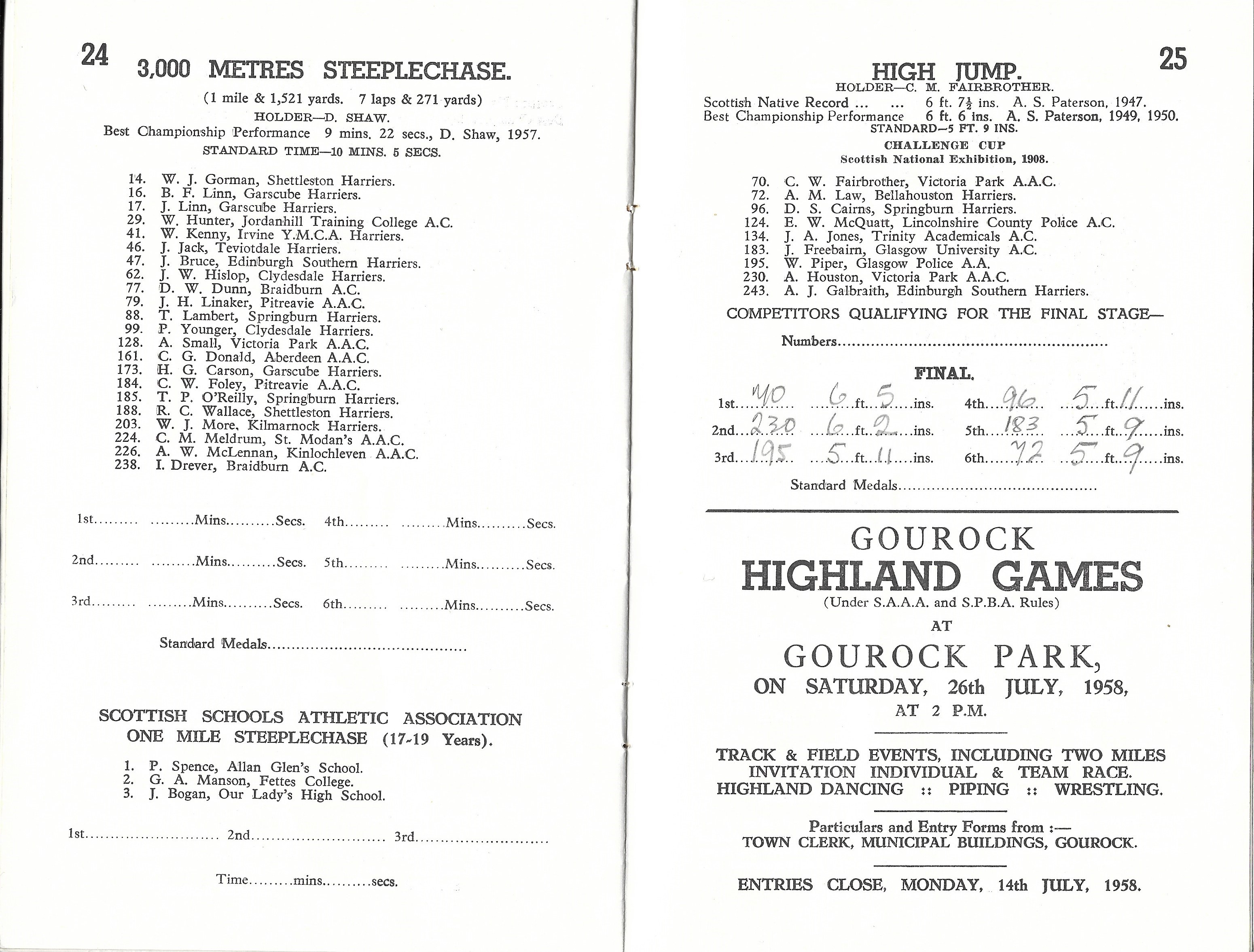

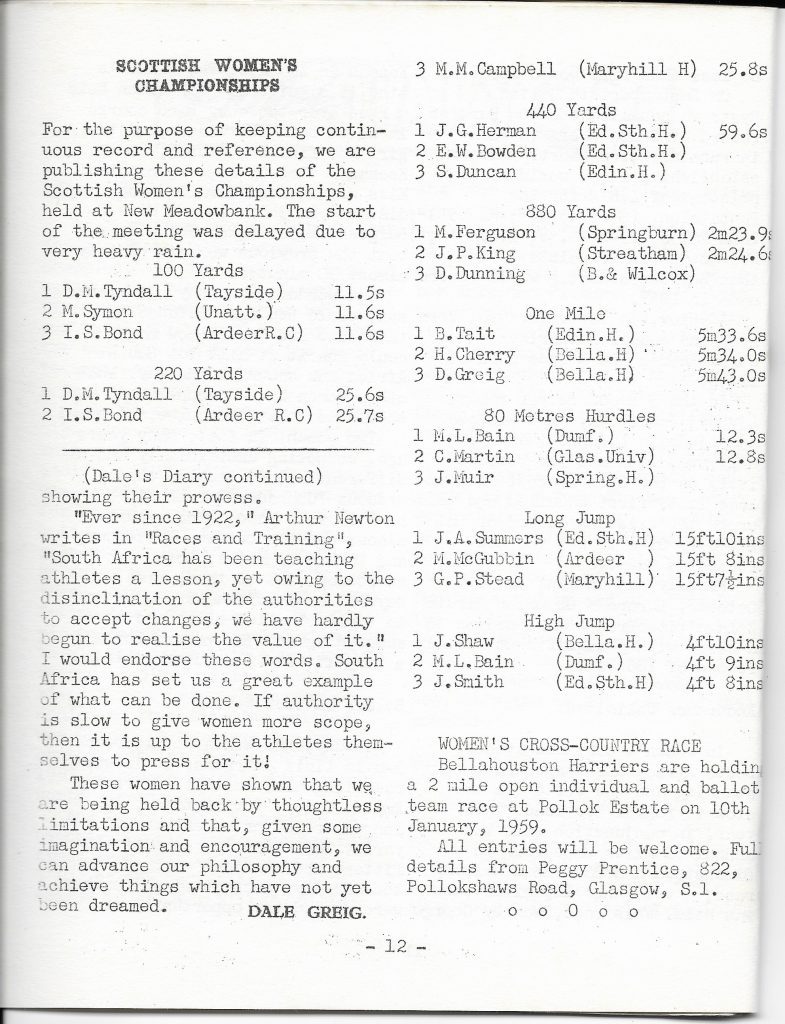

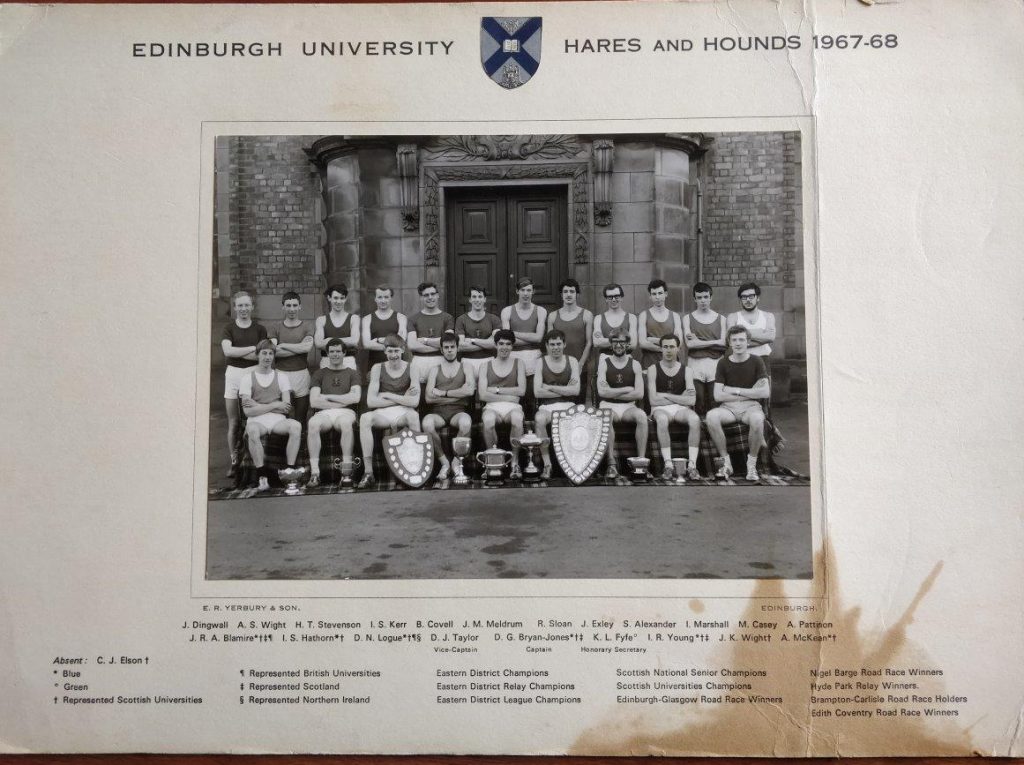

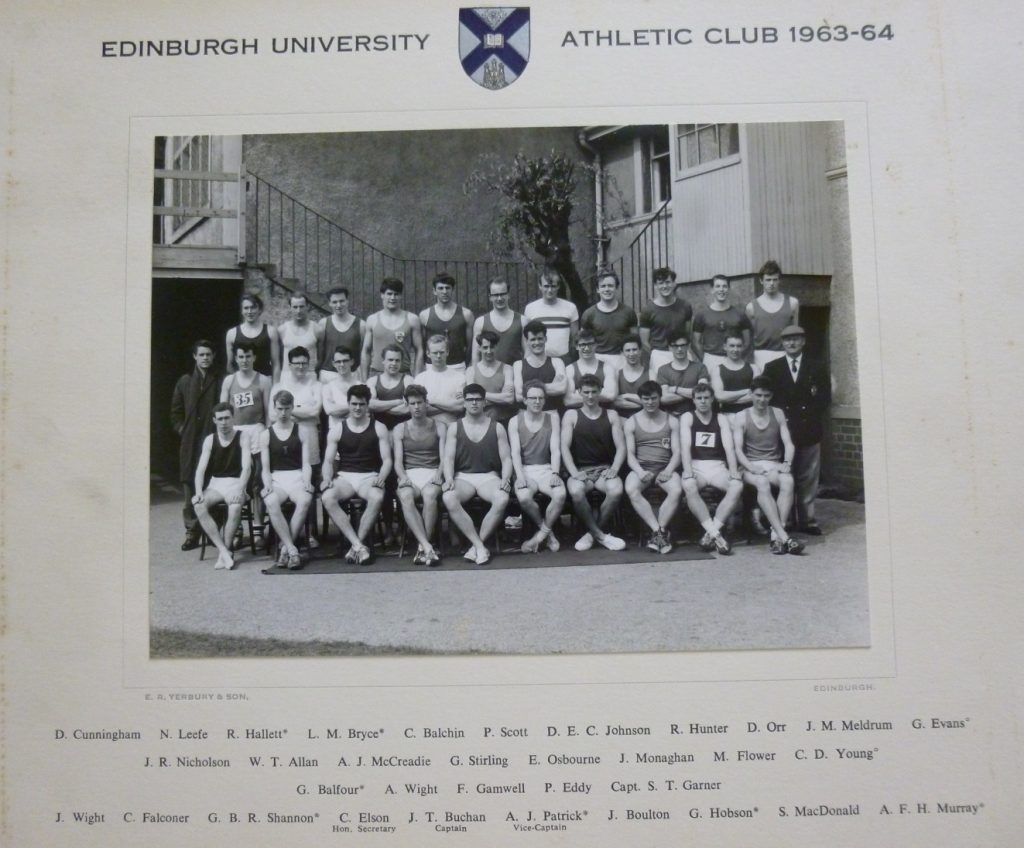

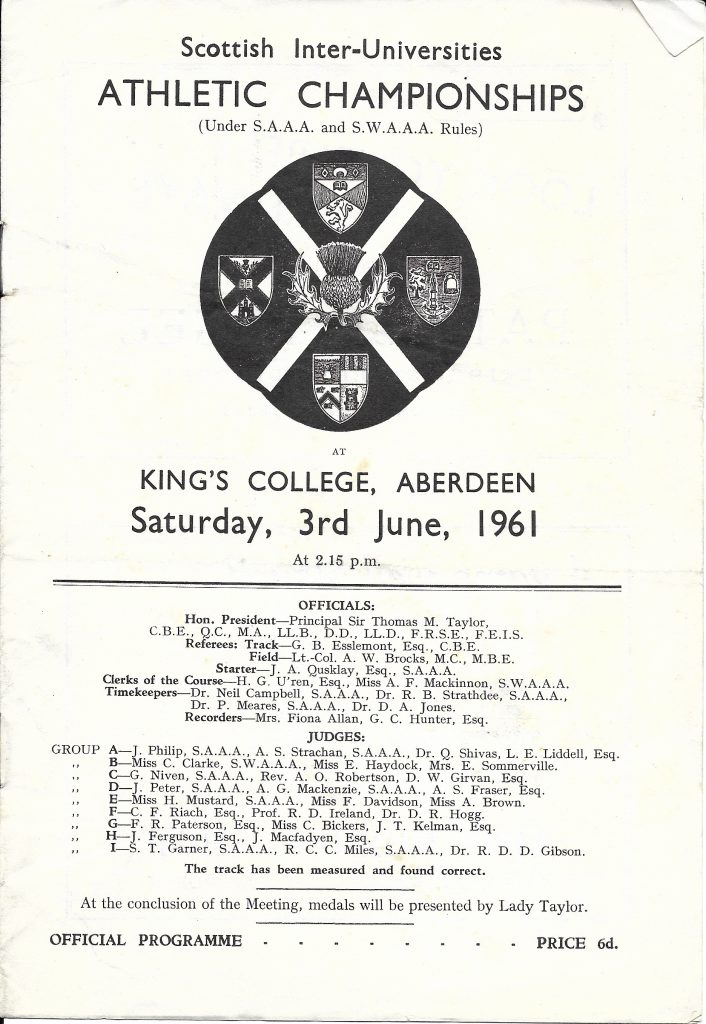

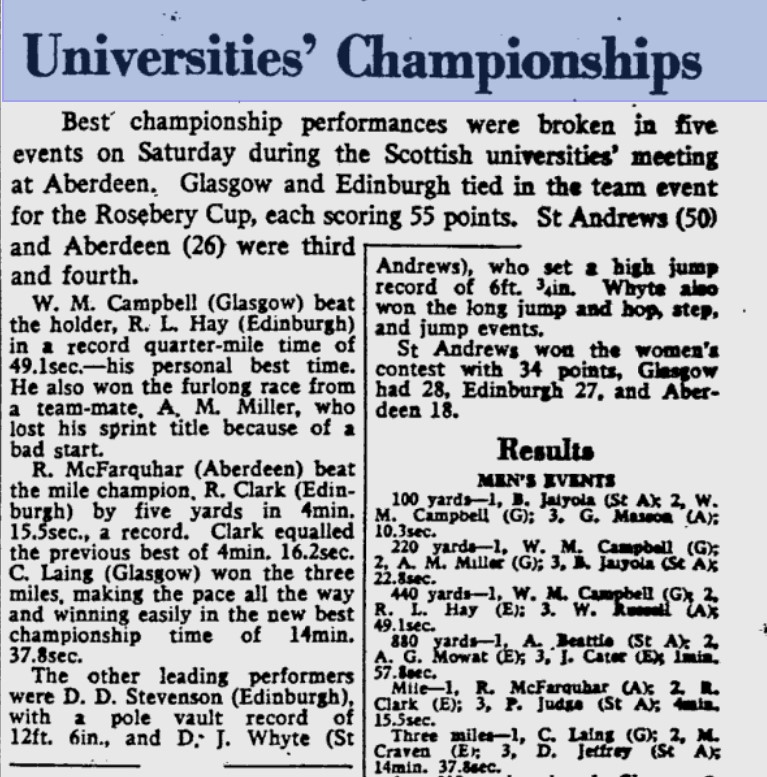

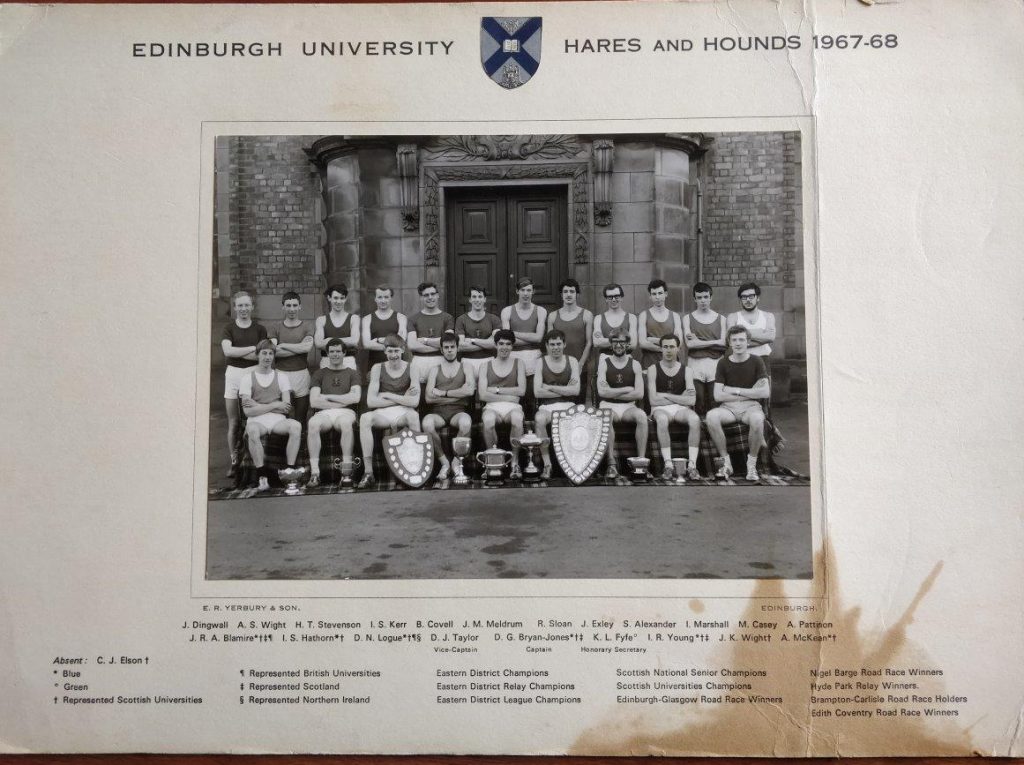

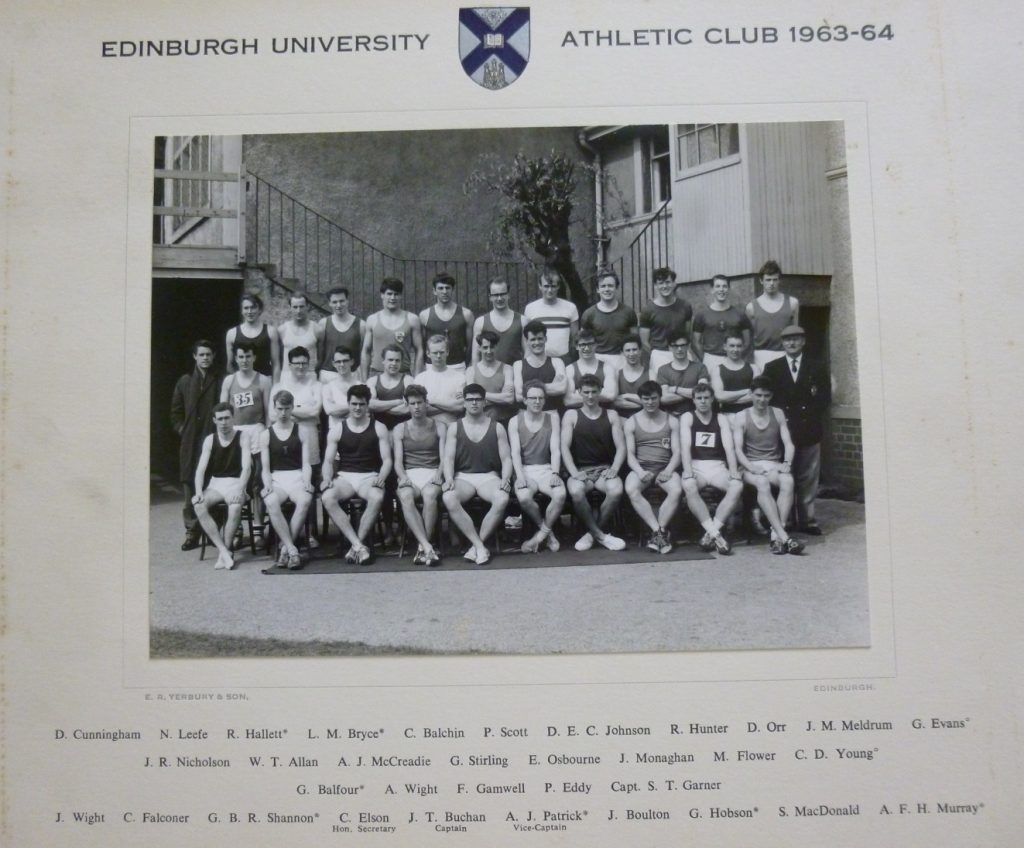

The EUAC team with the honours won by the members noted with the key at the foot.

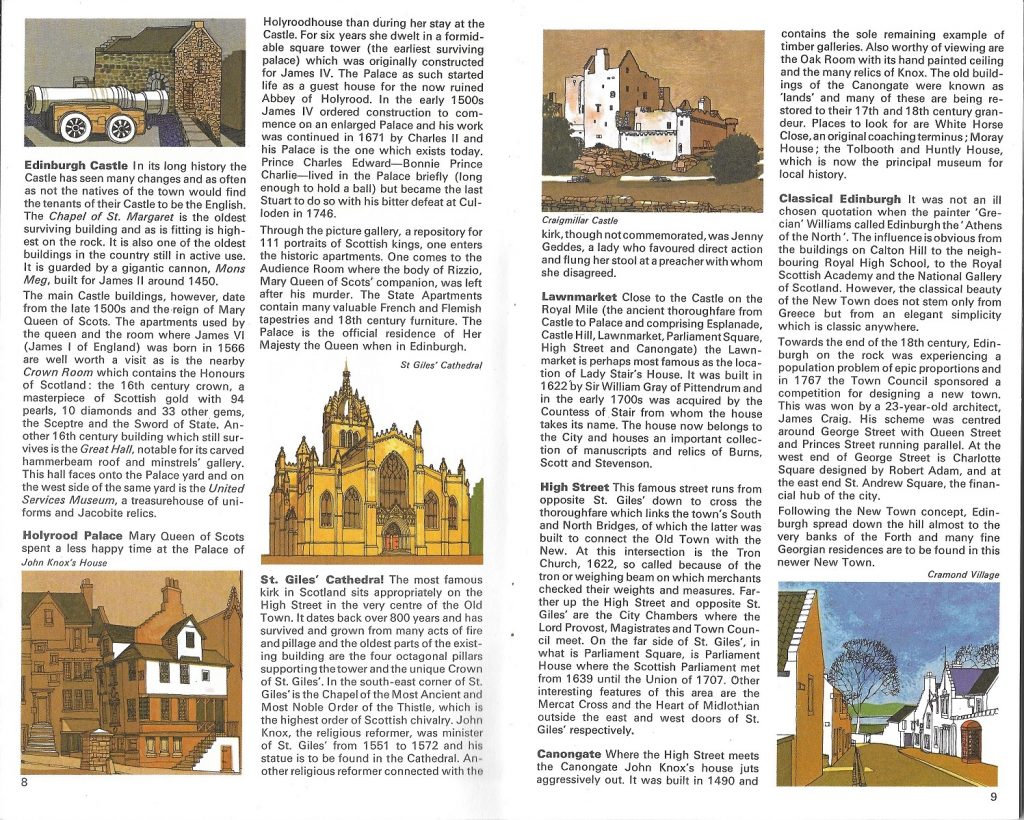

In Edinburgh, the situation was similar . Alistair Blamire was a member of the superb cross-country and track team in the 1960’s and has written a ‘must-read’ account of the period in his book ‘The Green Machine’. He says:

“In our day each sport put forward a list of people each year for consideration (for ‘blues’ and ‘greens’, which were ‘half blues’). A sub-committee of the Edinburgh University Athletic Club, which represented all sports and is now called the Edinburgh University Sports Union, then interviewed a representative (e.g. Captain or Secretary) from each sport, and a decision was taken on each nominee. I was on the committee in 1966-67 and I recall that we didn’t leave the room when our own sport came up, which was a bit ‘Non-U’ I suppose.”

When our team were doing really well the whole first team, and on one occasion a second team member too, were awarded blues. People bought blazers and ties depending on inclination (I had a tie). Quite a few runners had ambitions beyond the ‘blue’ so didn’t consider it a particular honour. I suppose Cambridge and Oxford ‘Blues’ carried more kudos.”

Just as the Glasgow University Athletic Club became the Glasgow University Sports Association, the Edinburgh University Athletic Club became the Edinburgh University Sports Union.

Ian Young who was also at Edinburgh in the 1960’s adds to the story when he says: “Edinburgh Blues were awarded for all round excellence rather than a single outstanding performance. Commitment to the team was paramount. I was particularly aggrieved in my first year when I was awarded a half blue, or ‘Green’ by the EUH&H despite having represented Scotland (ICCU Champs, Ostend, 1965), Scottish Universities, etc in my fresher year, but I was not awarded a Blue because I had not shown enough commitment to team events during that season, so it was not individual excellence which counted, it was a high level of performance throughout the season.”

The comment about continuous performance throughout the season is backed up by the comment “Awarded to those who have performed at a consistently high level for their club” on the University website in 2020. He goes on to speak of the actual award and what was involved:

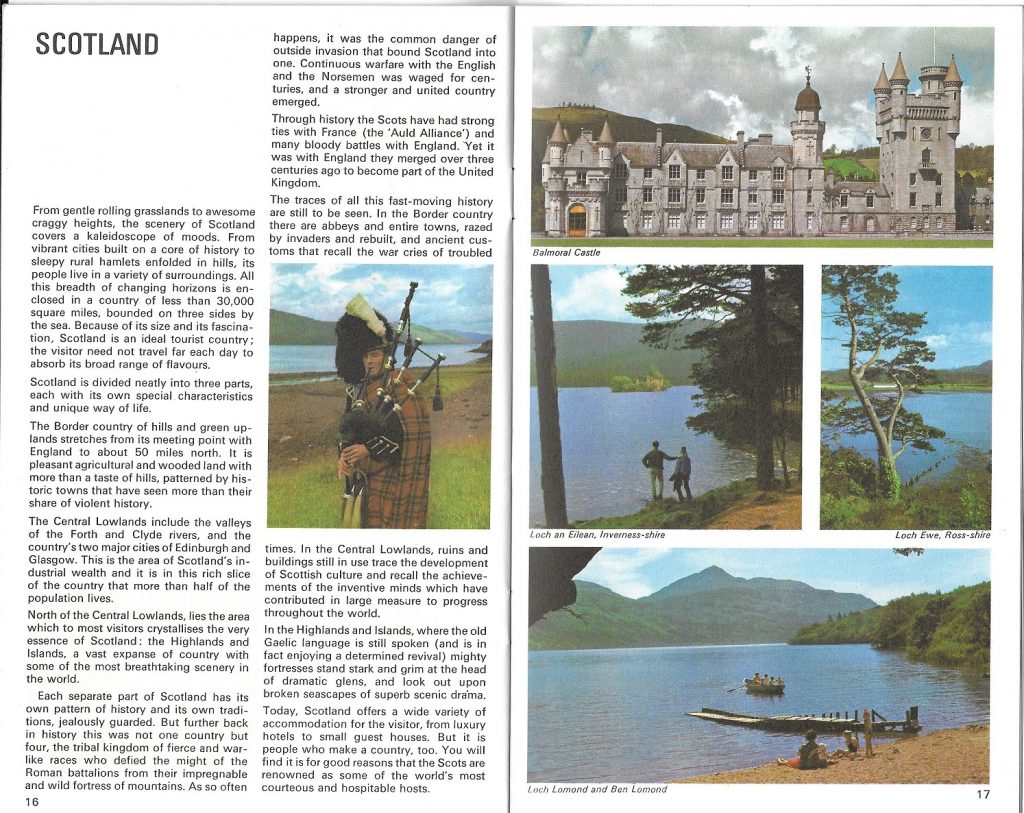

“In my case I had 6 Blues awarded during my 5 year university career, I think 4 from EUH&H and 2 from EUAC for track performance. In no case did I apply for or promote myself for the award. I believe the names were put forward to the EU Sports Union by the respective club captains and if accepted, the recipient got a note of the award which he or she could then take to the official University Outfitters to get the appropriate blues clothing. This consisted of the Blues blazer, tie and ‘Wrap’ which was a heavy scarf of blazer-type material which would have the initials of the recipient, sports section and award dates embroidered in white on the blue material. The blazer was an expensive piece of kit with the university crest, the sports section initials and the award dates all embroidered with real silver wire thread on the breast pocket. Again, subsequent dates could be added. The blues tie was blue silk with a diagonal silver stripe and no wording, so was the most commonly visible sign of that status.” There must have been at least a perception of a significant award when we look at the trappings: Ian’s description of the blazer and of the ‘Wrap’ are of items of real significance.

Ian Young’s Blues blazer with the crest and the wrap round the shoulders with crest on the left (both blues emvroidered)

and his initials woven into it on the right.

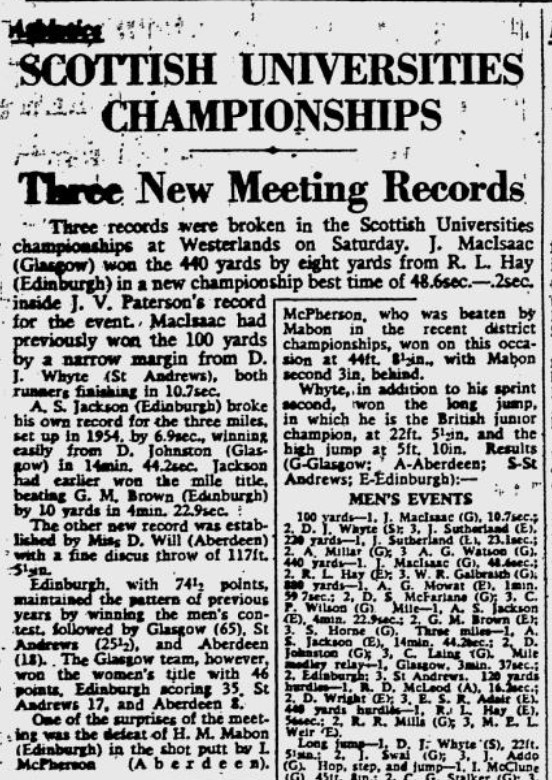

The two photographs of the University teams are notable for what they highlight. Ian tells us that “There was also the additional kudos in the end of season team photograph where individual names were followed by a list of symbols which denoted whether you were a blue or a green, Scottish internationalist, Scottish University representative, SCCU representative, etc and there was always great interest to see who had the most symbols!”

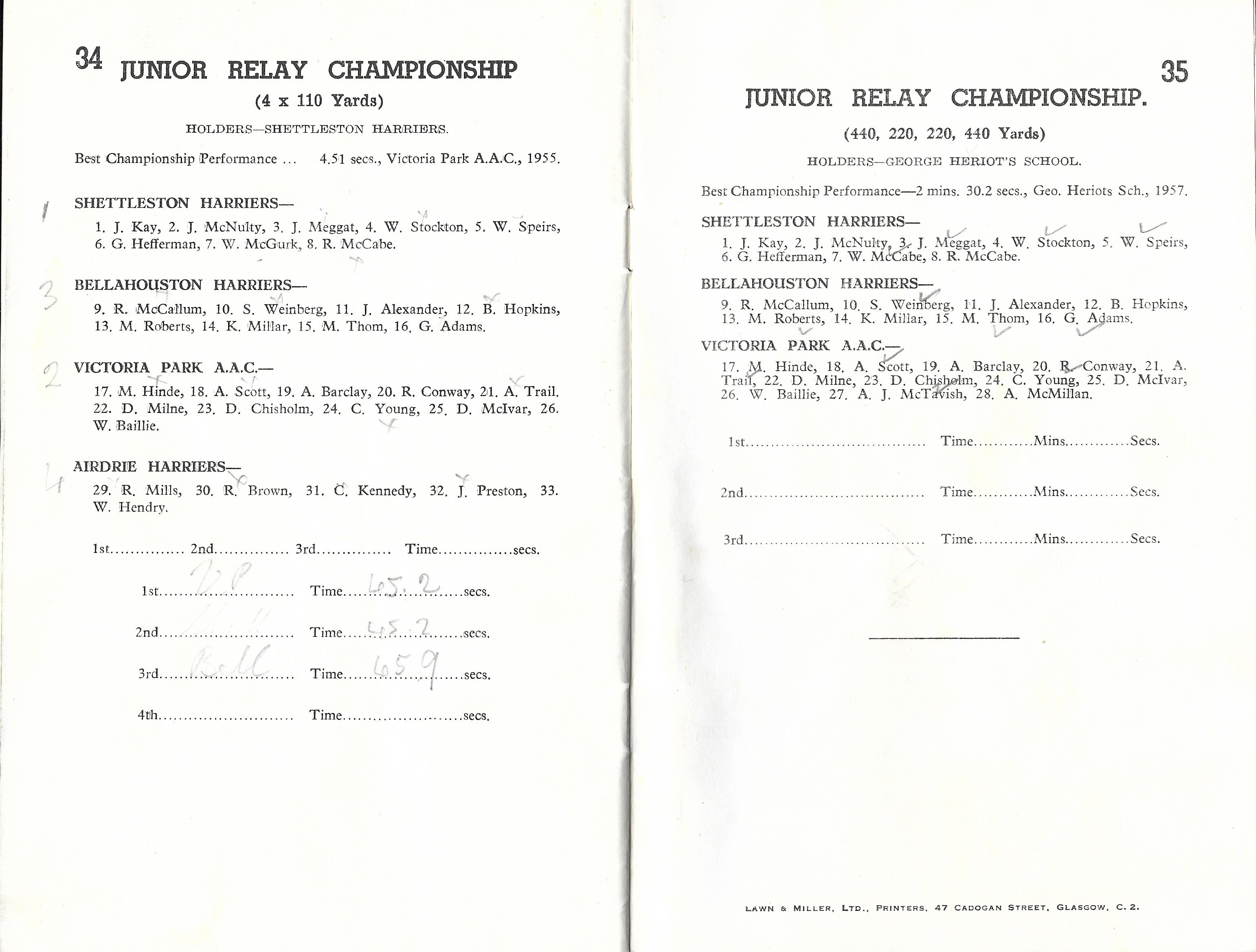

Another aspect of the Edinburgh scene was that there was a club called the Spartans, an elite social sports club which only recipients of Blues were entitled to join. This also had its own club tie and was a platform for Blues recipients across all the university sports clubs to meet as a common social grouping.

Note the starred athletes.

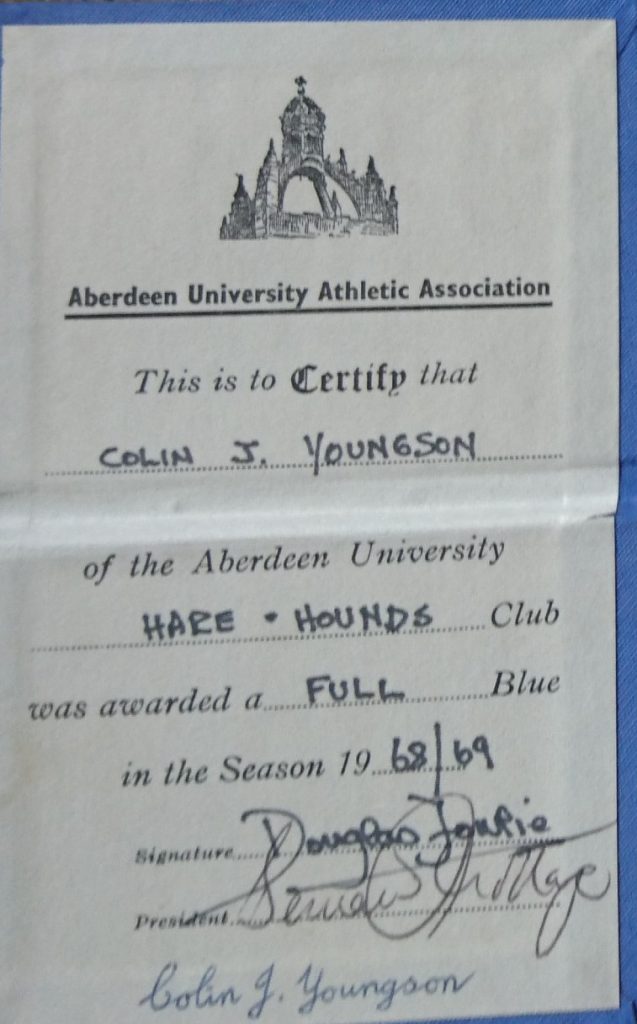

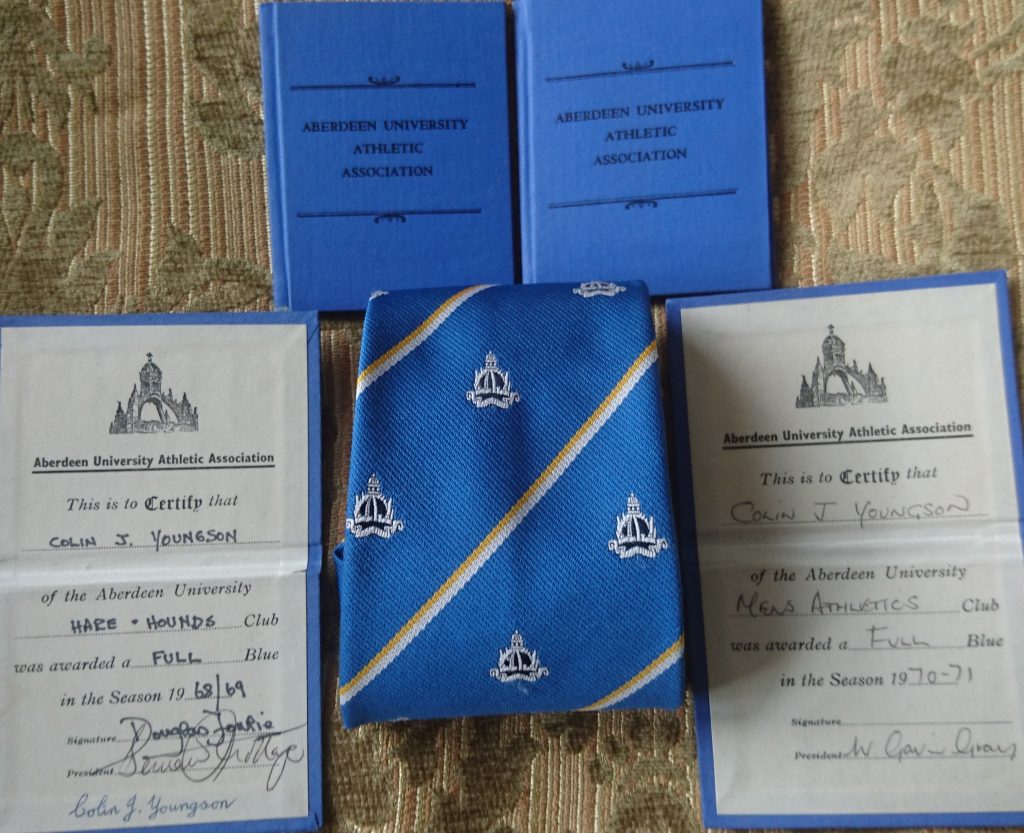

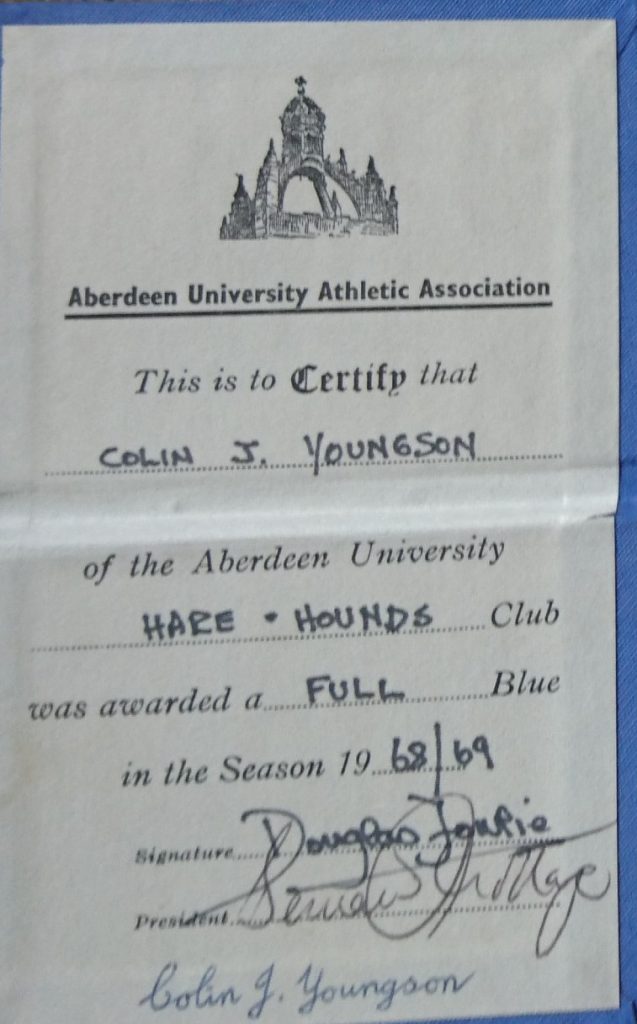

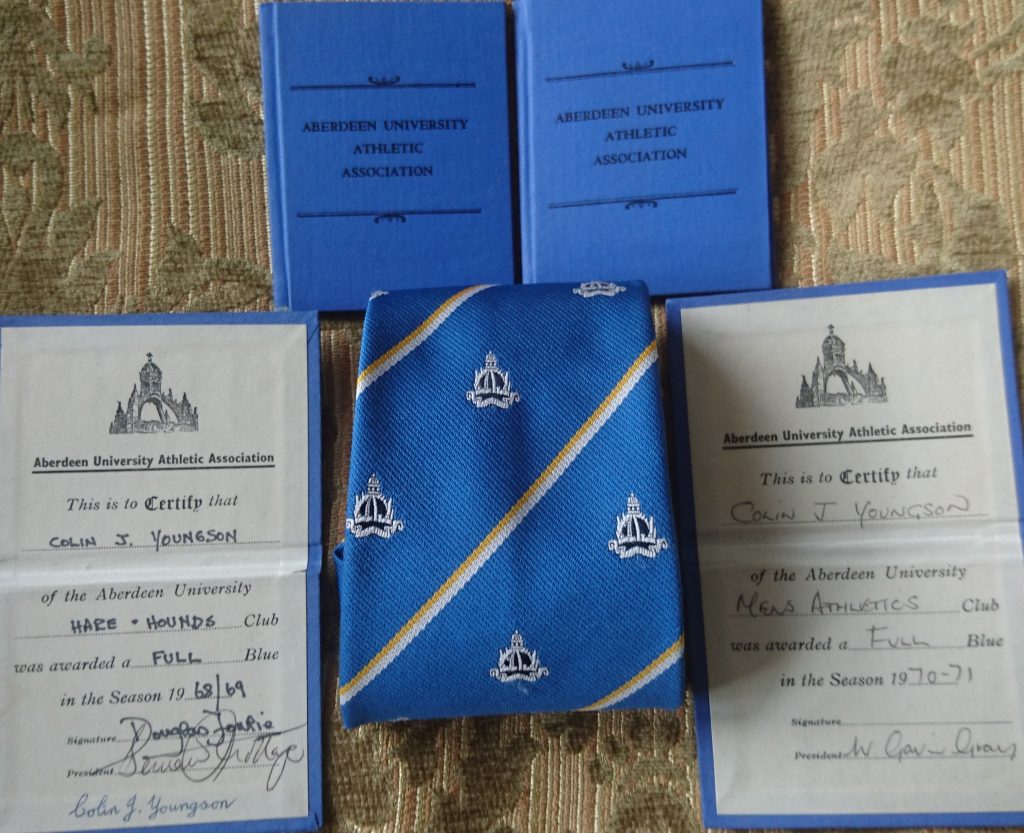

From Aberdeen we have Colin Youngson’s ‘Blues’ card, and some other memorabilia, shown below. Note that the tie is also there.

There was other paraphernalia associated with the award – Colin’s Aberdeen collection is below.

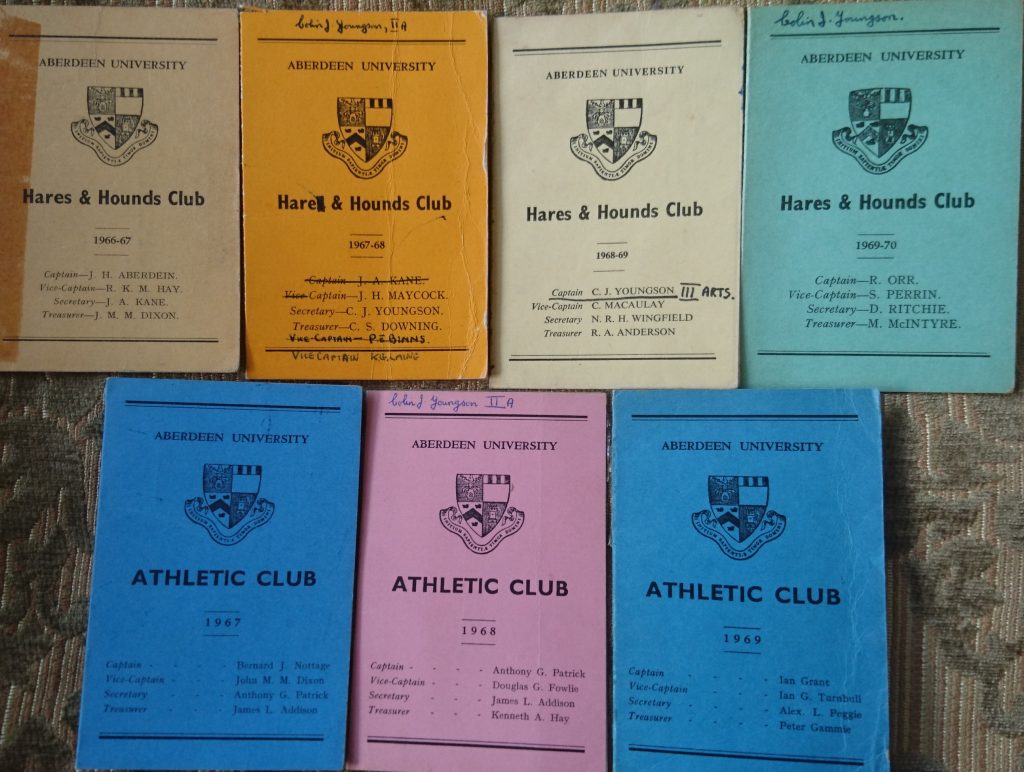

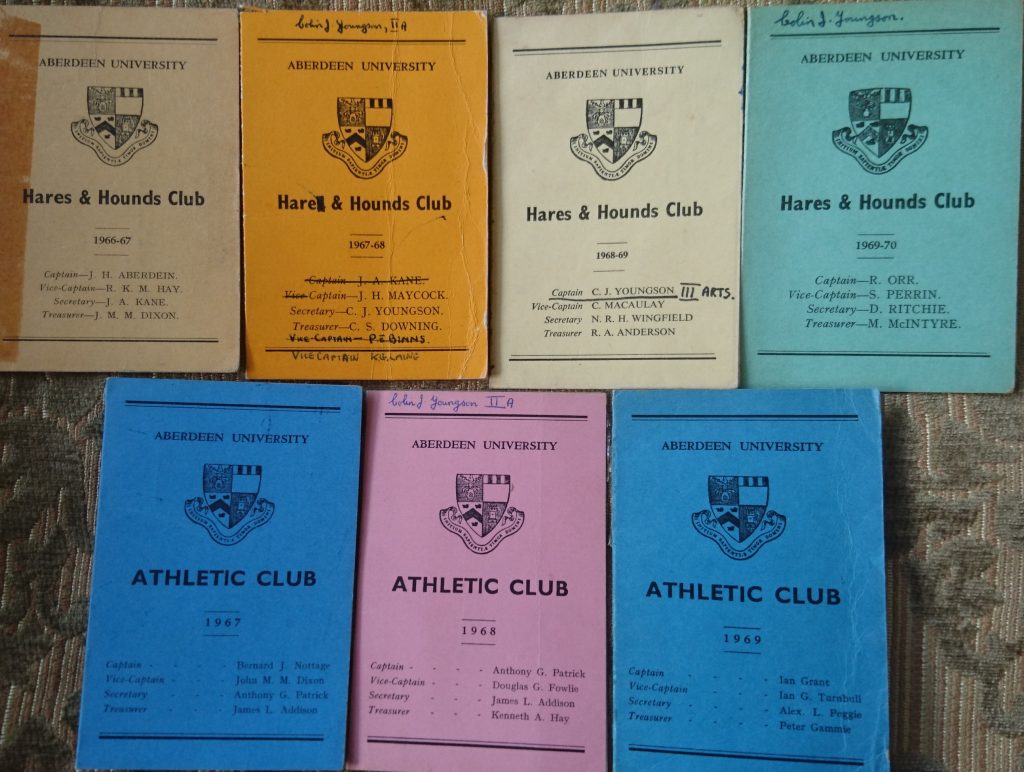

He also has his athletic club cards, a different colour each year to make it easier to see who’s up to date with the sub!

The card contained many things including the year’s fixture list

When we asked Colin about the Aberdeen University procedures, he said

“Aberdeen University based Cross-Country Blues on average positions against other universities in each fixture. For example if there was an AU v GU v EU match and I finished third overall, with two Edinburgh runners in front, my Blues score would be 3 + 1. If it was a 7 university fixture then AU v GU, AU v Strath, AU v HW etc would have to be worked out individually. To be even considered for a full blue, your Cross-Country race average for the whole season had to be under 3. Then performances in BUSF Cross-Country and the Scottish National might be considered by the AU Sports Committee, plus representing Scottish Unis against the SCCU or English Universities in BUSF. Decision (for a nomination for any sport) might be no award, half blue or full blue. Once a full blue, always a full blue- it could not be awarded twice.

For track athletics (and road running), Scottish National Standards were also taken into consideration. For example, in my last year at AU, trying to obtain a Full Blue for Athletics, I made up a nomination form featuring a) race average positions in track fixtures (I usually ran both 1500m and 5000m). Attaining National standards for Steeplechase, 10,000m, 10 Miles Track (plus a bronze medal in this race) and Marathon. Running 1500m for Scottish Universities v Irish and Belgian ones. Two decent races in the BUSF track champs in Birmingham. The AU Sports Committee’s decision was final – no appeals!

By my era (1966-71), hardly anyone bought an ostentatious and somewhat dated blues blazer. Most bought a tie and a scarf (powder blue!) which could be embroidered with white letters signifying Sport and date awarded – I lost mine somehow, but still wear the tie very occasionally, for example at Donald Ritchie’s funeral, since my old friend and rival often wore his.”

We now know that, unlike Edinburgh or Glasgow, Aberdeen had known rules for nomination for the awards with some scope for particularly good performances or meritorious selections to be taken into account. Like Glasgow, there was only one Blue for an athlete’s entire career. We also asked him about the ‘personal application’ aspect of the award and his response to both of these queries was as follows: “There were no repeat blues in the same branch of a sport. The sports person could go from half blue to full. I could only self nominate by my fifth and final year; otherwise the club would nominate or not nominate you.”

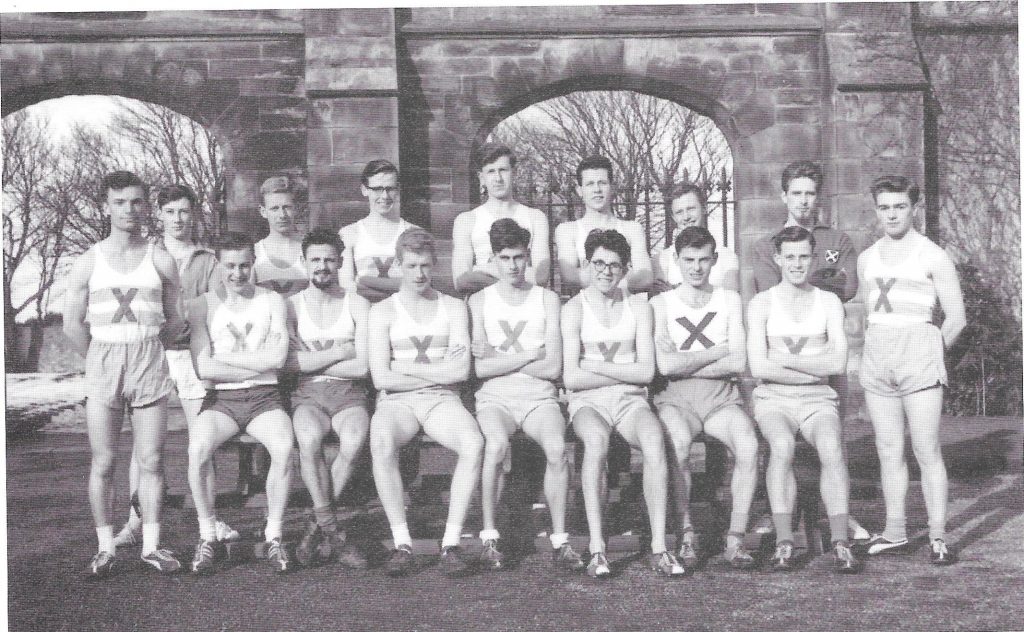

Colin is in the middle of the front row of the Aberdeen University team in the photograph below.

The St Andrews University website simply says about the Blue that: Full Blues are awarded to athletes with senior international representation. and Half blues are awarded to athletes who have displayed exceptional sporting achievement that is not at the level of a Full Blue. This is a bit different again but there have been many athletes from the University of senior international standard – Don Macgregor being the outstanding one. The route to a Blue was similar in all Universities and with the award of a Blue at St Andrews you were entitled to purchase a tie, a scarf and a blazer. The photos below illustrate all of these for 1956-7 as awarded to Ian Docherty. He was in the St Andrews team that won the National Junior and also had a Track and Field Blue. (He is also known for beating Ron Hill in a 3 mile race on the grass track in 15.05. ) For those who received the award, there was a dinner where the Blues were awarded and where you could wear the gear. Ian is pictured below wearing the appropriate clothing.

Scarf and tie

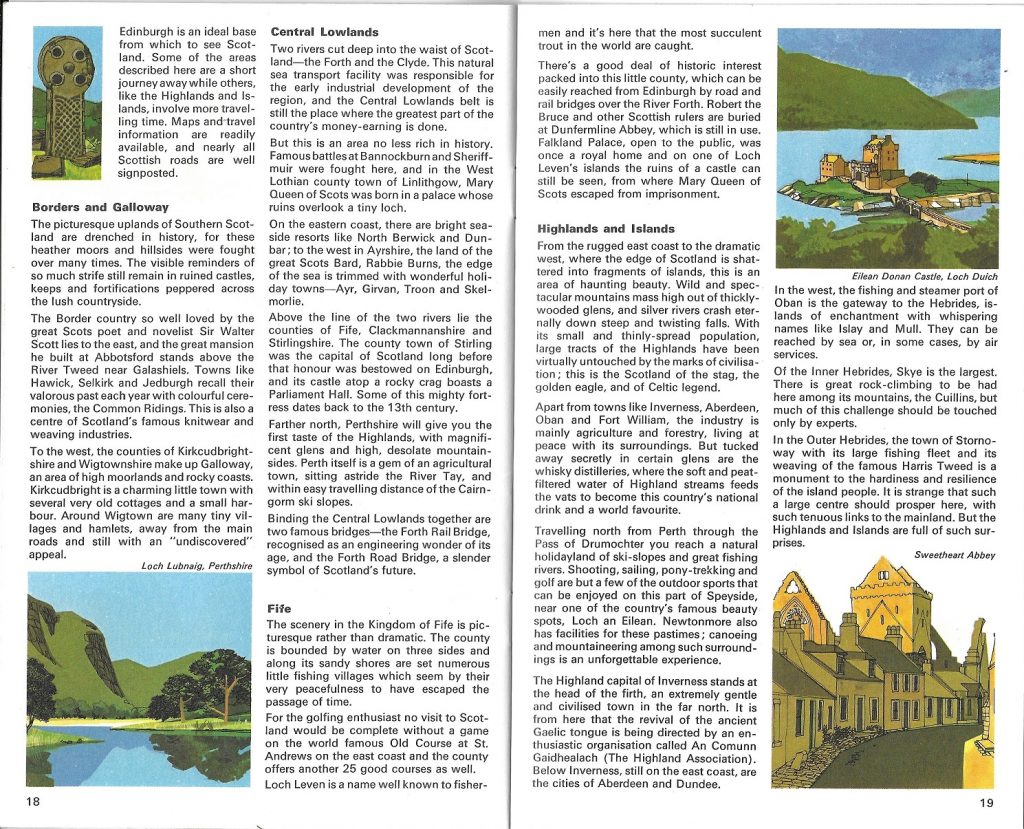

Given the standard however there will not be too many in any one year. The Photograph below is of the St Andrews Cross-Country Team of 1959.

*

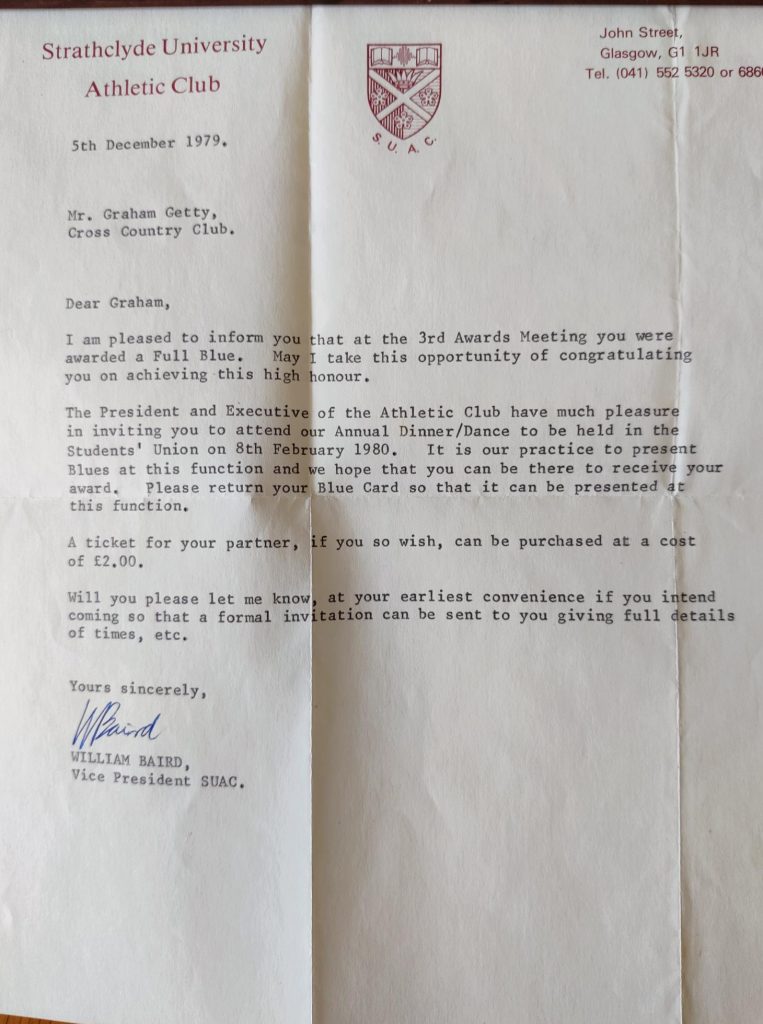

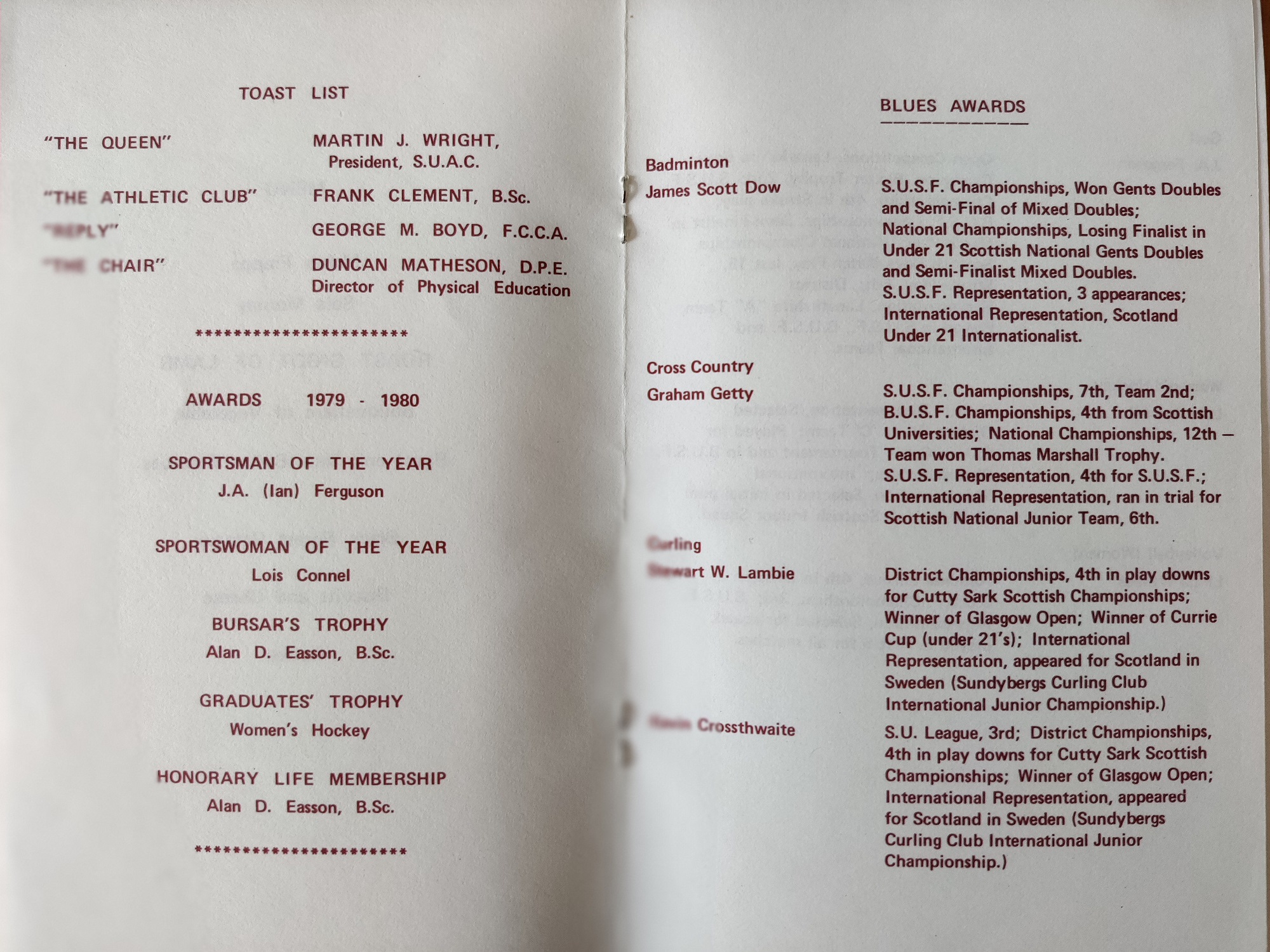

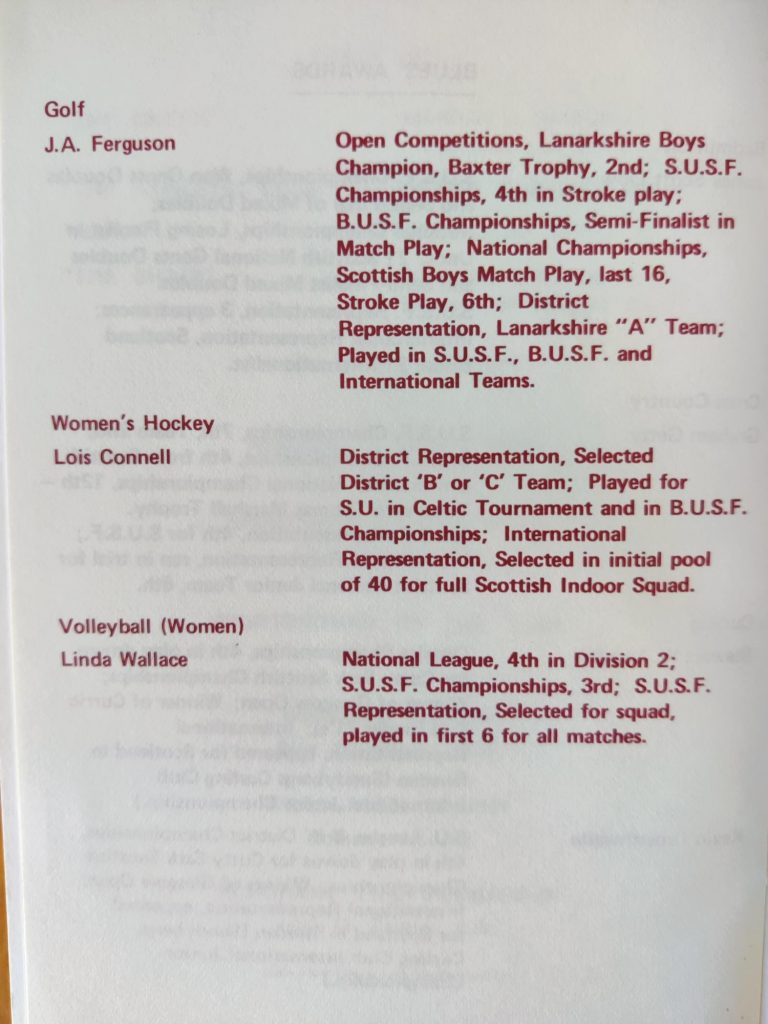

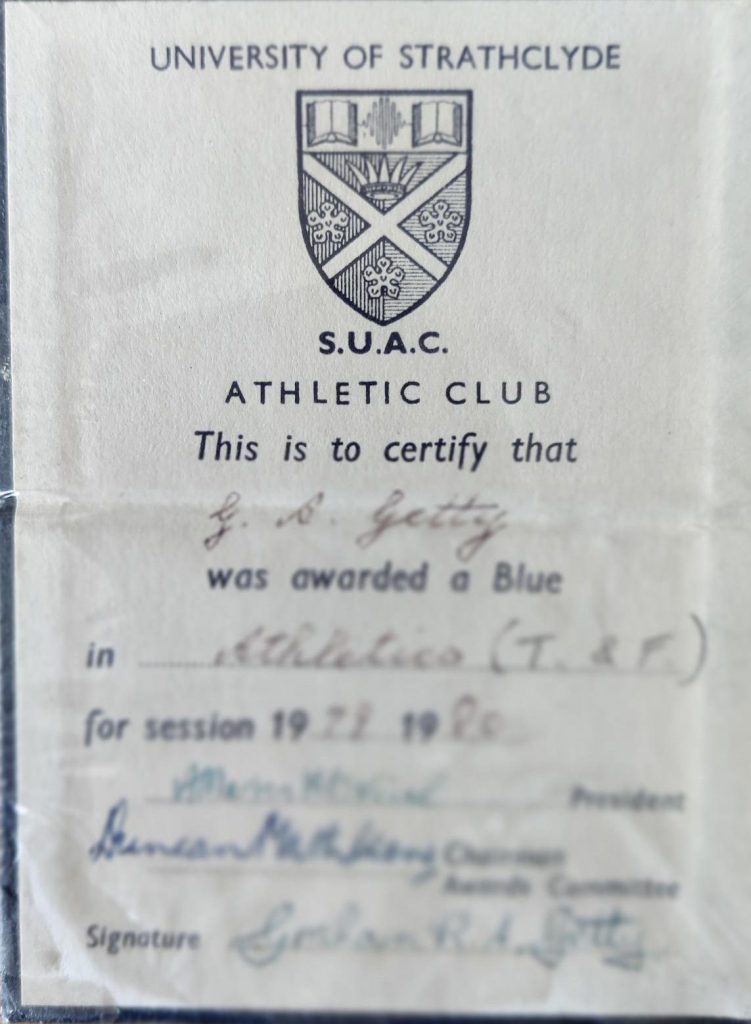

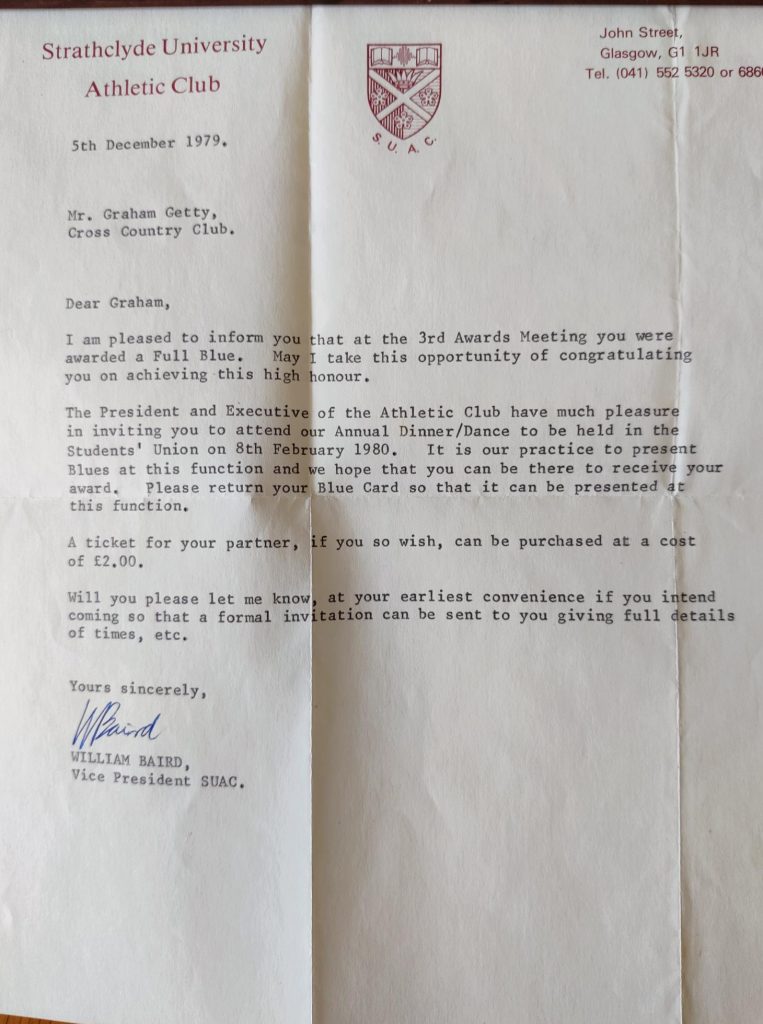

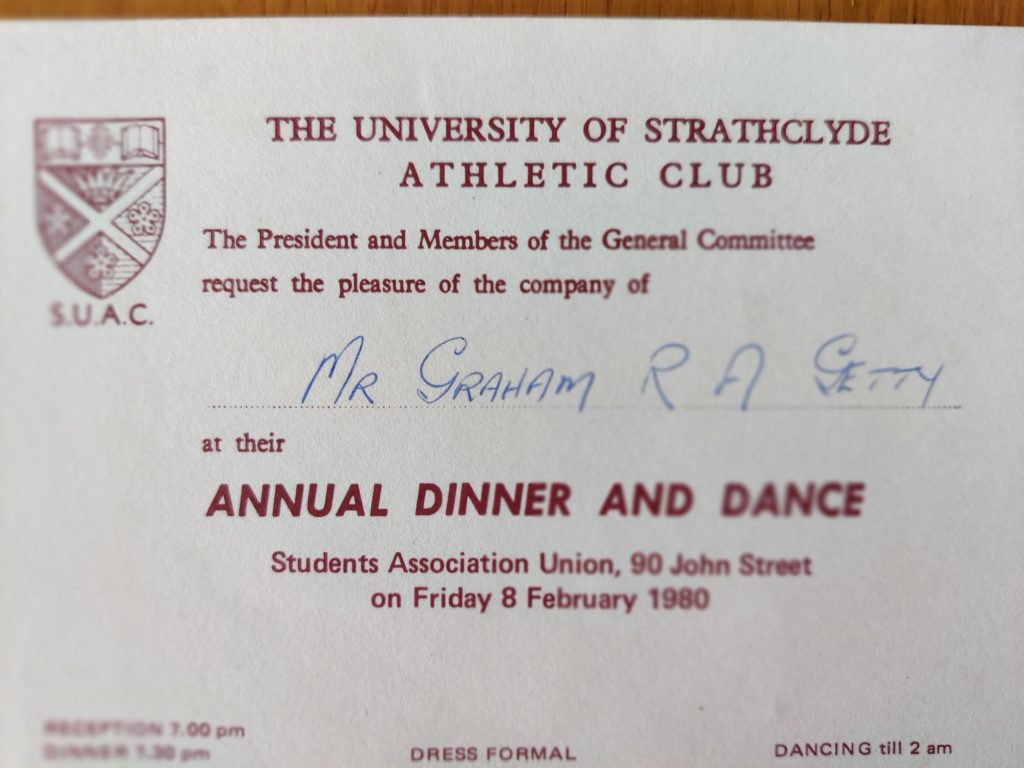

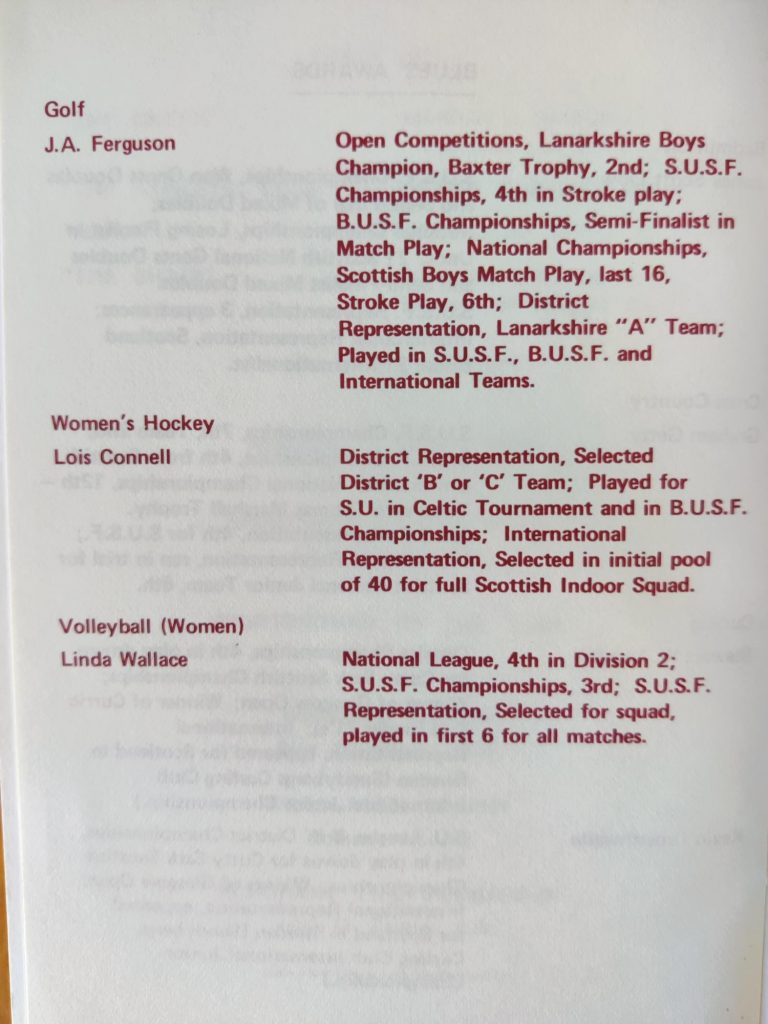

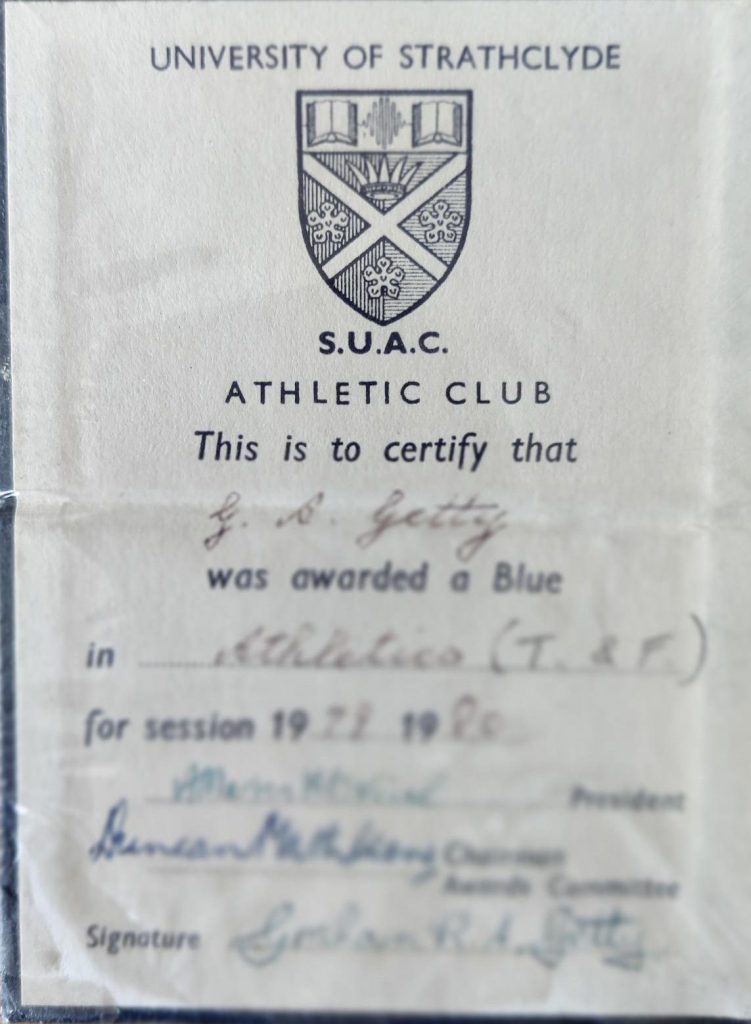

Strathclyde University in Glasgow also has its own Blues system and Graham Getty who has full Blues for Track as well as for Cross-Country in 1979. 1980 and 1981 has sent us some interesting material from his personal archive. A picture of the scarf first.

He tells us “On one side you see the SU badge and the years I was awarded Blues. From memory, I had to purchase the scarf from Rowans in Glasgow and then when I was awarded the 2nd Blue in the following year, I had to take the scarf back to Rowans so that the 2nd year could be sewn onto it). Scarf is made of a thick wool with a blue braid round the edges. On the other end of the scarf , you see my initials (G.R.A.G).”

The scarf is similar in style to the St Andrews and Edinburgh versions and it is interesting to see that sport people at the university could have more than one Blue. The procedure is also of interest. The first intimation that he had been successfully nominated for the award came in a formal letter from the University Athletic Club. The award would be presented at the Annual Dinner/Dance. The one below is for cross-country running.

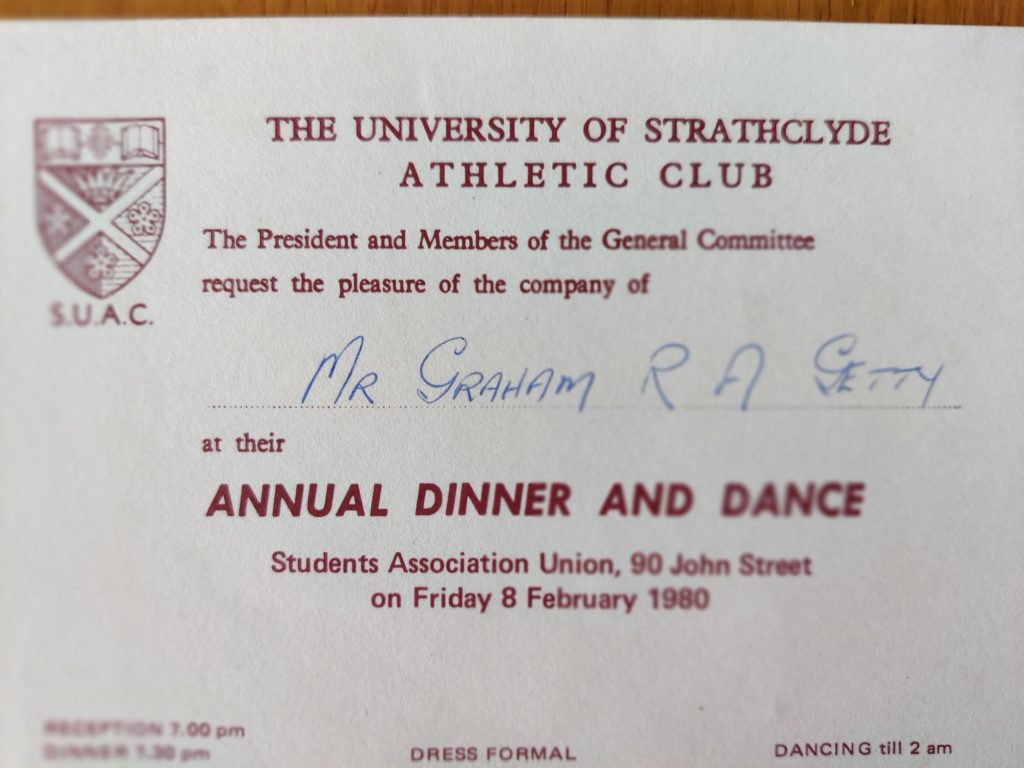

The athlete replied saying that he would be at the function in question and received the formal invitation.

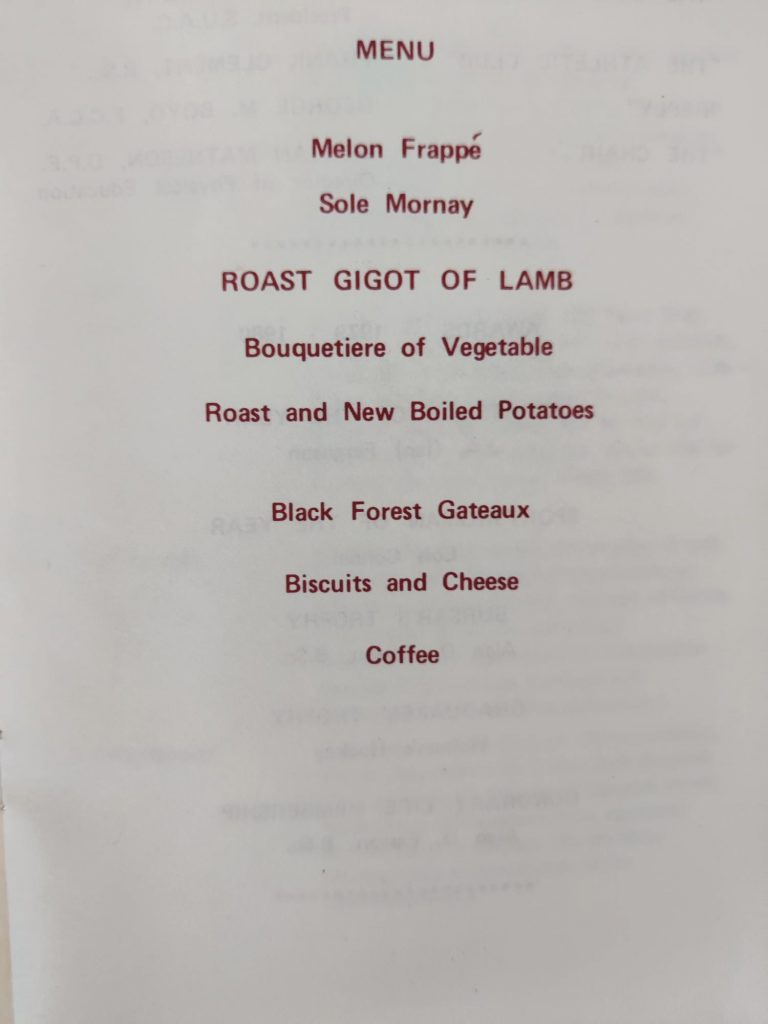

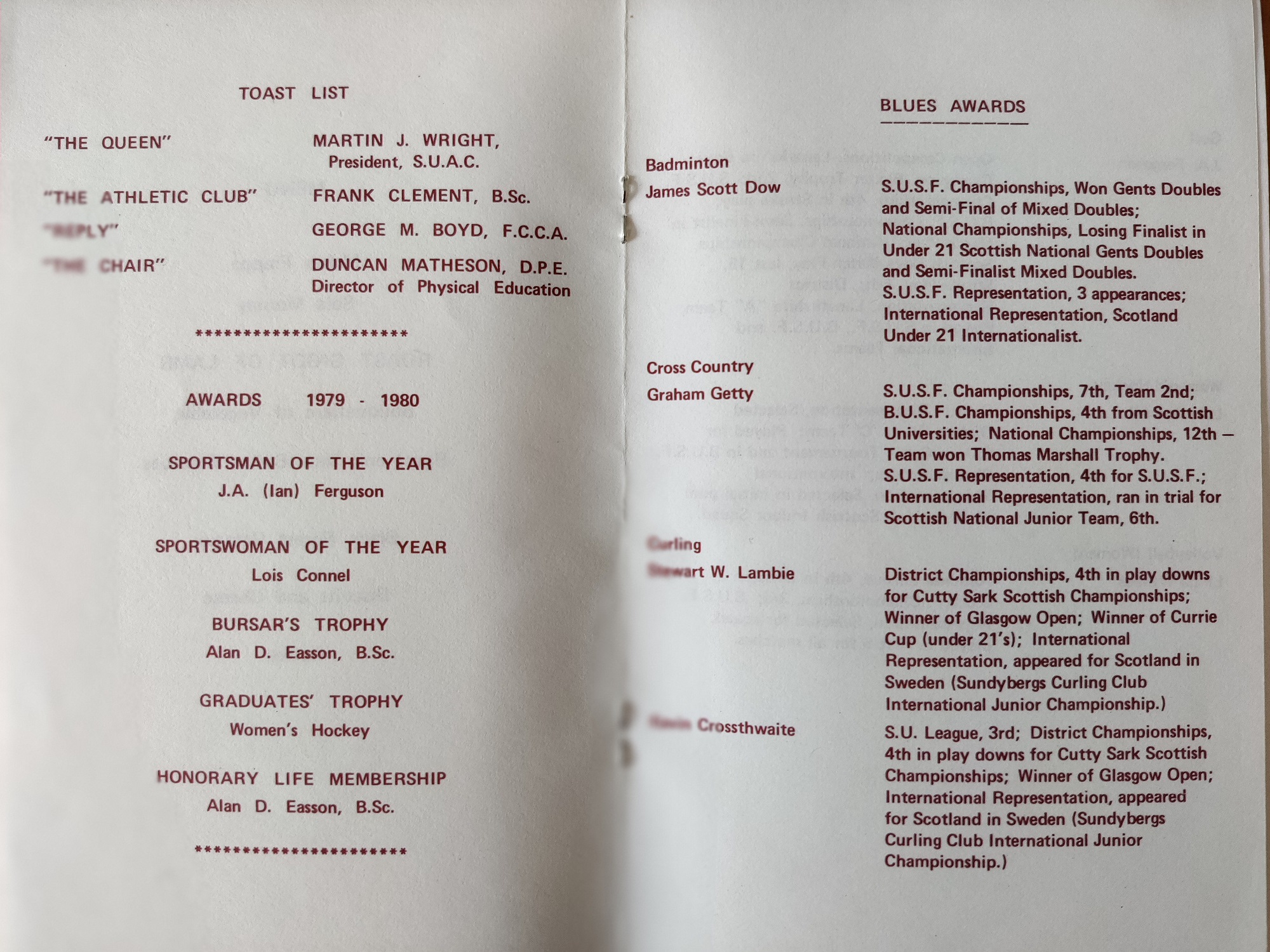

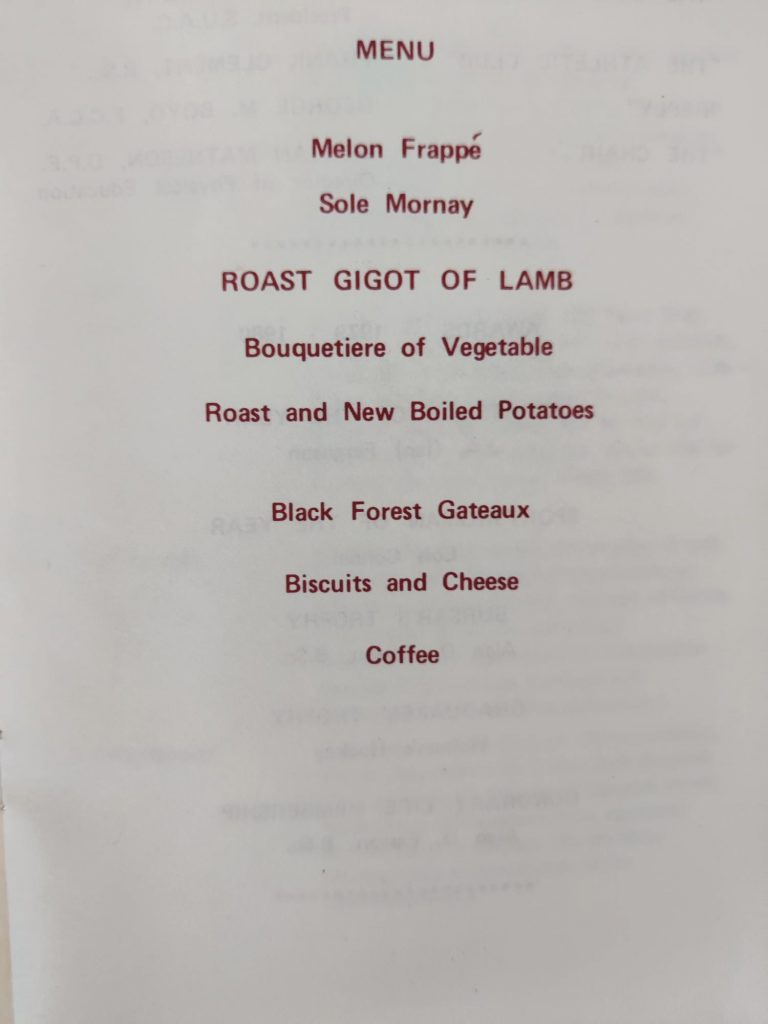

The function would take place on the due date and the menu contained details of the performances which had earned the reward.

There you have it – the full citation for Graham Getty. And that still was not all. There was the presentation and he has a copy of the official photograph of the presentation being made by Mrs Frank Clement.

There was a Blues certificate which, apart from being a mini-treasure in its own right, allowed the holder to buy the official scarf and tie plus access to other benefits that fell to a Full Blue of Strathclyde University.

There are more of Graham’s Blues documentation at the link.

Despite the casual dress code of the 21st century, it is perhaps surprising that so many former Blues still have at least the Blues tie. There are also quite a few with the certificate or authorisation card.

There are however issues associated with the awarding process and its, often apparently unfair, results. Sandy Sutherland tells the following tale.

“Regarding the actual Blues award itself I assume we all copied it from Oxbridge where it was initially awarded to those who had actually competed in the annual Oxford v Cambridge match in what ever sport and not all sports were considered worthy. We had a great example of this in basketball when one member, now nearly 90 and a distinguished student of the stars – he was i/c the Royal Observatory at Hurstmonceaux n Sussex I believe – – went to Cambridge and actually captained them to victory over Oxford round about 1953-55 he told me! He was only awarded a HALF Blue as the Blues committee at Cambridge did not consider Basketball a sport worthy of a FULL Blue. Why? Because not all the players on the bench at one time were on the court!! Only the rowers in the BOAT are awarded full BLUES! And to this day – and much to his irritation he has never received his FULL Blue.”

As a graduate of Glasgow who did not run for the University, I knew many of their runners, met them in the Union and at races, there were some issues that present themselves. One of those was the question of how the Blues Committee compared the relative merits of those recommended. I asked Douglas McDonald about this and his comment was that “In the early to mid 90s I was invited back onto the Blues committee as an ex-president external member. Many of the same problems mentioned above were evident. Over the course of two years I encouraged the committee to invite clubs to submit objective standards for what they thought would be an appropriate level to award a blue, arguing that this would mean that the award would not be about personalities and would have consistency beyond the life span of rapidly changing club committees. It would mean that the blues committee would have to invest more time considering the initial proposals but that the subsequent awards could be done with very much less fuss. (obviously the committee would be open to any club that wished to adjust their objective standards at a point in the future). I believe that work started on this but I don’t know if it was ever achieved “. In the course of writing this, I have followed up his point and it is doubtful if his recommendation has been followed through. It would seem to me to be very difficult to compare the various activities that St Andrews was awarding their Blues for in 2019. eg how do you compare the relative merits of Dance and football? Is a Senior International appearance for lacrosse equally valid to one for rugby? Is a 10th place in the national cross-country less worthy than a GB representation at Frisbee?

Blues in the 21st Century

This may be totally irrelevant in the 21st century however when it may be that the Blue has lost a lot of its significance. When I took up the sport in 1957 and was talking to another runner about Bobby Calderwood of Victoria Park I was told that he was the first runner not to run for his university but to go on representing his club. That was a time when the Inter-Varsities was a major meeting and the University clubs were well represented at the SAAA Championships and in international teams. Bobby’s decision had been an eye-opener for many. Record holders and champions like David Gracie were representing their Universities (in his case, Glasgow) and not their clubs (Larkhall YMCA). International teams had University athletes turning out in numbers – Douglas Edmunds, Adrian Jackson and many more wore the dark blue.

But by the 1980’s the situation was a lot more mixed. The situation developed until in the 1990’s top quality athletes like Alistair Douglas, Victoria Park, were running for their clubs for almost the entire year but turning out for the University in inter-university events. Alistair Johnstone who was in a similar frame of mind, ie studying at Strathclyde University but running mainly for his club, only racing for Strathclyde in the Scot Unis and BUSF championships said when asked: “I wasn’t eligible for a Blue unfortunately because I maintained VPAAC as my First Claim club and therefore competed against Strathclyde in Open competition. However I thoroughly enjoyed training with and competing for them in confined university races and helped them a lot – 3rd team place in Hyde Park Relays 1969 , 3rd individual Scot Univs. c c champs. 1969 , 16th. in BUSF c c champs 1969 ( and counted along with Edinburgh University’s lads in winning Scot. Univ.’s team to beat UAU’s team) – also I was usually first or second to John Myatt in various inter university. c c events.” The fellow feeling was there but having come up through the ranks with Under 15’s, Under 17’s and Under 20’s with a club, having many friends at the club, it was the allegiance that was strongest for the runners mentioned.

This led to the obvious questions, “What is the current situation regarding the award of Blues at Scottish Universities? Does the modern student in the 21st century value the award as much as their predecessors did?” Given the the four ‘ancients’ still make the awards, a look at some University websites revealed that many of them do and that they are part of a structured programme of sport. For instance, the University of the Highlands and Islands says

What are the Sporting Blues?

- Colours – To receive a Colour, athletes, where applicable, need to serve and play for their club and to be regular 1st team members, representing the team in at least 65% of the eligible matches, recording at least one victory.

- Half Blues – Awarded to athletes for playing well above the average standard for a University 1st team (where applicable) or represent the University as an individual in national level competition.

- Full Blues – Awarded to athletes of outstanding ability judged by standards applicable to students’ different sports.

- Sports Person of the Year – This is an award for truly exceptional athletes, the panel will decide annually whether to award it, with the decision following the same criteria as that for a Full Blue

- Honorary Blue- Honorary Blue – awarded to athletes that have won medals at World Championships, World Cups, Commonwealth Games, Olympic Games or equivalent relevant to their sport. The award may also be made to a person connected with UHI with an outstanding contribution to University, Scottish, British or world sport.

This is very similar to the other systems noted above but is slightly wider in the formal recognition of an Honorary Blue.

One of the first ‘new’ universities to join the established four universities in the early 1960’s was Dundee University and their website in 2020 says:

“The Blues and Colours Awards celebrate the finest in student sport at the University of Dundee, across the country, and recognising achievements by students for their competitive success or club commitments as a volunteer. From our athletes competing nationally on the world sporting stage representing Scotland or regionally representing the university, to those who have gone above and beyond in their chosen sport giving that extra time to advance the development of their club.”

It is also possible to read about Blues and their awards at several other universities such as Strathclyde, Stirling and Heriot-Watt but the most recent additions to the 19 degree awarding institutions in the country do not as yet have a sports structure which supports these awards despite having several courses dealing with sports or sport related topics. The situation seems to be then that most universities award Blues to their outstanding sportsmen and women. Most also follow the traditional method of individual sports making a nomination to a central blues and awards committee for approval. The criteria are institution specific, and the criteria for the award are set at that level.

There are some differences though.

The range of sports is much wider, over 60 sports are recognised for Blues awards across the country and this makes the evaluation of nominations more difficult. As an example, we can perhaps look at the 2020 Blues awarded by St Andrews University. The totals were 8 full blues, 38 half blues with 16 sports represented and 22 sports awarding Colours. These receiving the awards include Boats, Cheerleading, Cricket, Dance, Football, Netball, Pool, Sailing, Shinty, Tennis, Trampoline, Triathlon, Ultimate and Waterpolo. I am reliably informed that Ultimate (originally known as Ultimate Frisbee) is a non-contact team sport played with a flying disc. I am further informed that St Andrews has a highly organised coaching system for the sport with serious training done throughout the week.

The Universities, then, continue to award Blues as before in the 21st century albeit for more sports. Blues winners are now entitled to their certificate, usually a medal and the right to buy a tie. The days of Blazer and scarf/wrap are largely things of the past. One thing that hasn’t changed however is the Awards Ceremonies. The award entitles the winner to attend the Ball or Dinner, depending on the institution which is a real social highspot. The awards themselves have a great deal of cachet and the sports clubs that have winners gain some prestige by doing so. The Blues live on.