Kirkcaldy YMCA began in 1886 in the Swan Memorial Halls in Kirk Wynd. It started off mainly as a bible study group for young men before moving into other areas of young people’s life, including physical activities, tuition and even a public baths.

Kirkcaldy was always a focus for running and Colin Shields in his official history of the SCCU tells us that there was an East District Championship in 1899 which was won by J Harcus of Kirkcaldy Harriers, so there must have been some such activity before 1900. Graham McDonald points out that there are three other clubs from the area named in the East District League Minutes – Kirkcaldy Boys Club joined the League in 1928, Kirkcaldy Old Boys in 1931 and Eastbank AC also in 1931. None of them lasted for long and Kirkcaldy YMCA emerged as the local club. According to the local Press the YMCA Harrier Club started up in 1909. The following announcement appeared at the foot of a column of the Dundee Evening Telegraph of Wednesday, 1st September, 1909. It read

“KIRKCALDY YMCA START A HARRIERS CLUB

At a largely attended meeting held in the Swan Memorial Hall last night it was decided to start a Harriers club to be known as the YMCA Club. The club has secured the promise of several well-known sprinters to join and runs are to be arranged at a later date. The following office-bearers were elected:- Captain Mr JR Christie; Vice-Captain Mr J Seath; secretary Mr J Ferguson; committee Messrs J Gibson, D Gray, and JS Marshall. Monday and Friday were selected as running nights.”

Monday and Friday were not usual Harriers training nights and they were later altered to Tuesday and Thursday, with the club training from Valley Gardens in Kirkcaldy.

The club’s founding fathers knew what they wanted in a harrier club and, in addition to the two nights a week training, they set about organising events that would get them noticed. Just over a month after that first meeting, this appeared on Friday 29th October, 1909, in the Dundee Courier: “KIRKCALDY YMCA HARRIERS ARE TO HAVE A MARATHON. Kirkcaldy YMCA Harriers have arranged to have a marathon race, open to all amateurs in Fife, on New Years Day. The club have been successful in securing the promise of a handsome silver cup. The start of the route for the race will be at the club rooms in the Swan Memorial Hall. The runners will then go right along the High Street and Links Street and out into the country round by the back of the Kinghorn Golf Course and the Loch. The homeward journey will be through Burntisland and Kinghorn and finish at the clubrooms. It is anticipated that the Provost Munro Ferguson, MP, will act as one of the officials at the start of the race.”

There was a report in the Scotsman of 3rd January, 1910, which read: “A Marathon Race was organised on Saturday by Kirkcaldy YMCA Harriers. The route was from Kirkcaldy to Burntisland and back, a distance of about thirteen miles. Nineteen competitors took part. Prize winners:- 1. J Gilchrist, Matkinch; 2. WA Ransay, St Andrews University; 3. G Robertson, Dysart Harriers. Club winners:- G Lawson and D Ramsay. Time 1 hour 4 minutes.”

The race was obviously a success – 19 runners, a fast time and all on 1st January. So much so that a year later, on Monday, 17th October, 1910, in the Glasgow based Scottish Referee: “A few members of Kirkcaldy YMCA had a splendid run of six miles on Saturday. This club is only in its infancy but its members are doing ther utmost to boom cross-country running in the ‘Lang Toon’ where a few years back it had a good hold, and we hope to see it regain its popularity again this season.”

In addition to the two week nights, they soon began to hold Saturday runs, Press notes appeared like this one, in its entirety, on 16th December, 1910, Scottish Referee: “Tomorrow’s Fixtures: Kirkcaldy YMCA Harriers … 3:15 Short and to the point – members would be looking for it.

The ‘marathon’ of the previous year had been successful and they had another run at it. On Monday 19th December, 1910, the Scottish Referee reported: “Entries for the Kirkcaldy YMCA Harriers ten mile race to be held on Jan 2nd close on Dec 26th. The event is to be decided under SAAA laws.”

And further down the same page – “Kirkcaldy Harriers hold a ten mile run on Saturday in view of the club’s open ten miles race.”

The race was duly held and reported on by the Scotsman of 3rd January, 1911. “The second annual Marathon race run under the auspices of the Kirkcaldy YMCA, for which the principal prize is the Fife Free Press Challenge Cup, took place at noon yesterday. The weather conditions were ideal. The route was by way of Auchtertool and covered some pretty hilly country. Although the distance set was stated to be ten miles, only about nine miles were covered, as “through a misunderstanding” the runners omitted to include two laps of Beveridge Park. Sixteen competitors took part, including Alex McPhee, junior, Clydesdale Harriers, a Scottish Junior Champion. The race was a very close one, only four seconds covering the first three runners. The prize winners were:- 1. Alex McPhee, Clydesdale Harriers, 55 min 24 sec; 2. H Hughes, West of Scotland; 3. GH Ramsay Edinburgh Southern Harriers; 4. J Hastie, Stirlingshire Central; 5. WA Ramsay, Edinburgh Southern; 6. J Stewart, Dundee Thistle Harriers; 7. J Gilchrist, West of Scotland (last year’s Winner); 8. G Lawson, Kirkcaldy YMCA.

Just as they were getting into their stride in Scottish athletics properly, along came the 1914-18 war and activities were put on hold for the duration.

They started up again after the hostilities and were back holding club races, championships. inter-club runs and getting involved in open races quite quickly. Like many another club they discovered the importance of having patrons and the following item appeared in the Fife Free Press and Kirkcaldy Guardian on Monday, May 26th, 1923:

“KIRKCALDY YMCA HARRIERS.

The above mentioned club is now in strict training for the Hexathlon Competition of the YMCA when practically every event has to be carrier through for maximum points. In answer to a letter from Mr J Cameron, secretary of the club, asking Sir Robert Hutchison to assist by bec0ming Patron, the under-mentioned is a copy of the reply received:-

House of Commons, 18th February. Dear Sir, I will gladly become a Patron of the Kirkcaldy YMCA Harriers and I am sure you will produce runners who will hold their own with anyone. Believe me, I much appreciate this chance of associating myself with such a club. Yours very truly, R Hutchison.”

It was the 1920’s and the club was doing well with all the activities that go to make up a successful athletics club – regular training (two nights and a Saturday), regular racing, club championships, fund raising activities, local and district competitions as well as national. There were reports in all the local papers and every week there was something about or by the club.

The sport at this time was a bit different to the one practised in the twenty first century and we could take a look at a typical year as seen through the eyes of the local Press. By 1924, the War was well over and the club was starting to perform really well If we take 1924, and look at local Press reports and we get a bit of the flavour of the club.

Saturday 12th January, 1924: Fife Free Press: “Kirkcaldy YMCA Harriers decided the Davie’s Gold Medal Handicap on Saturday when a dozen competitors took part in the four and a half mile run from St Brycedale Church by way of Townsend Place, Dunnikier Estate, Overton Road, and Den Road, finishing at the starting point. The conditions were favourable and a good contest was provided. A Thompson (2 3/4 mins) was the winner, the time taken being 24 mins 5 secs, while A Wright (4 1/2 mins) was placed second, his time being 25 mins 25 secs and D Candlish (4 1/2 mins) was third, his time being 26 mins 35 secs. he record time was broken by J Cameron who accomplished the distance in 23 mins 5 secs, half a minute faster than last year’s winner. The handicapper was R Christie, formerly of Kirkcaldy YMCA now of Edinburgh University Hares and Hounds.”

Monday 8th February, 1924, Dundee Courier: “KIRKCALDY YMCA HARRIERS IN CLOSE FINISH. Champion Beaten. A fine race was witnessed in the Kirkcaldy YMCA Harriers Open Championship on Saturday which was run off on a very trying course. The route was over the Dunnekier Estate and three of the seven miles was water sodden ploughland. J Grant was first home after a great finish, R Christie wh has held the cup for two years, coming in close behind Grant. The winner broke away at the end and was timed at 42 minutes 45 seconds, 15 seconds before Christie. Biggar was third. The trophies were presented at a smoker after the race.

Monday 11th February, 1924 The Scotsman: “The annual cross-country championship of the Eastern District of Scotland was held at Galashiels on Saturday. …. Ten teams and about 120 runners started from the Gala policies and covered an excellent course of about seven miles. ….. The weather broke down just as the race started and there was a driving wind with sleet and rain. … Team result:- 1. Edinburgh Northern 55 pts; 2. Gala Harriers 118; 3. Dundee Thistle 133; 4. Edinburgh Southern 146; 5. Heriot’s Athletic Club 200; 6. Edinburgh Harriers 226; 7. Teviotdale Harriers 276; 8. Kirkcaldy YMCA 328; 9. Edinburgh University Hares & Hounds 339; 10. Falkirk Victoria 345.

Monday 18th February, 1924 Dundee Courier : “The members of Kirkcaldy YMCA Harriers Club had a team race on Saturday from St Brycedale, the course being round the Beveridge Country Park, a distance of two and a half miles. There was a good turnout and, the conditions being admirable, the run was a most enjoyable one. The winning team was R Young, who finished third; J Wood who got in fifth; and A Mills who was eighth to finish, their points totalled 16. A fine finish was witnessed, the individual rizes going to R Bigger who accomplished the distance in 13 minutes 50 seconds, R Cameron who was 15 second later and R Young who was 15 seconds behind the second prize-winner.”

Monday, 1st March, 1924, Dundee Courier: “An inter-club run along with Edinburgh Harriers and Edinburgh Northern Harriers was carried out on Saturday when a distance of six miles was covered, from the club rooms to Forth Avenue North, and afterwards into fields covering a circular route and home by way of Dunnikier. At the end of the run a fine finish was made, which resulted in Peter Gourley, Kirkcaldy Harriers, being first for the slows, and J Gardiner, Edinburgh Harriers, first for the fasts. The slow pack was paced by J Thompson, Kirkcaldy Harriers, and the whip was A Sinclair, Northern Harriers. The fast pack was paced by JRP Smith, Edinburgh Harriers and the whip was J Cameron, Kirkcaldy Harriers. On the whole the run was very satisfactorily carried out. A social evening was spent in the Carlton afterwards.”

Monday, 8th March, 1924, Fife Free Press & Kirkcaldy Guardian: “KIRKCALDY YMCA HARRIERS. The past two weeks have been taken up with practices for the coming ten miles road race on Saturday, March 15th, when the ‘Fife Free Press Cup’ is at stake. It is expected that this will be a very keen race. An ordinary club run takes place today.”

Monday 17th March, 1924, Dundee Courier: KIRKCALDY YMCA HARRIERS. The ten mile marathon race carried out under the auspices of the Kirkcaldy YMCA Harriers for a silver cup and gold badge, was run on Saturday under good conditions. The route was from St Brycedale Church by way of Boglily Road, Glassmount to Kinghorn, returning by the main road. A splendid race was witnessed, the result being:- 1 S Hunter; 2 P Gourlay; 3 J Lees.”

There was further coverage of this race in the Fife Free Press on Saturday, 22nd March, 1924, which added: “… The actual time for the winner was 1 hour 10 mins 55 seconds. One of the favourites got second place. He had a handicap of seven and a half minutes and his time was 1 hour 7 minutes 25 seconds. G Calder, who is the best timed man for the distance covered the route in 1 hour 5 mins and 10 secs. R Biggar, the champion of the club, was second for time, which was 1 hour 6 mins 30 secs. Calder had 3 minutes of handicap and Biggar was scratch. Cameron, last year’s holder, did not compete through accident, and so the ‘Fife Free Press Trophy’ changes hands.”

Saturday, 29th March, 1924: “On Saturday last a practice run was carried out. Today the Novice Championship takes place commencing from the top of Kirk Wynd for a distance of about four miles.”

Monday, 5th April, 1924, Fife Free Press & Kirkcaldy Guardian: “The novice championship of the Kirkcaldy YMCA Harriers club was decided on Saturday when splendid weather conditions were experienced. The starting point was St Brycedale UF Church, and the route was one of four miles. The results were as follows:- 1 J Wood, 28 min 05 sec; 2 D Candlish 30 min 07 sec; 3 A Wright 32 min 07sec. An ordinary race was run in conjunction with the above. R Biggar covering the distance in 27 mins.”

Saturday, 10th May, 1924, Fife Free Press: “The club members are in training at present for the YMCA National Championships contest which is to be carried out between July and August at Stark’s Park. A rally is to take place at the YMCA next Wednesday evening.”

Friday, 19 September, 1924. Dundee Courier: KIRKCALDY YMCA ELECT OFFICE-BEARERS. At the annual general meeting of Kirkcaldy YMCA Harriers Club, the resignation of club president (Mr DC Blewes) was intimated, and he was specially thanked for his valuable services. Some forty members were present at the meeting, and the office-bearers for the ensuing year were elected as follows:- President Mr Geo. Sandilands; Vice Presidents Mr T Christie, Mr R Rough and Mr R Barrie; hon. secy. Mr J Cameron; hon treasurer Mr George Calder; auditors Mr JM Thom and Mr J Brodie; captain R Biggar; vice-captain J Braid. The opening run will be on Saturday 27th September.

Monday, 13th Oct, 1924. Dundee Courier: “The members of Kirkcaldy YMCA Harriers club competed in a cross-country race over a course of about three and a half miles on Saturday for a prize presented annually by Mr James Bogie. The weather was fine but the going was somewhat heavy. The fastest time was that by Mr R Biggar (scr) who covered the distance in 17 minutes 30 seconds. The results were:- 1 Mr P Philp 17 min (handicap 2 min 30 sec); 2 JS Cameron 17 min 30 sec (2 min 30 sec); 3 R Biggar 17 min 30 sec (scr); 4 J Walker 17 min 50 sec (2 min 30 sec).”

Friday, 28th November 1924, Dundee Courier: “Kirkcaldy YMCA Harriers have selected the following team to compete in the McKenzie Trophy relay race which is to take place in Edinburgh on 6th December:- R Biggar, P Philp, J Cameron, P Gourlay. Reserves G Calder and J Smart.

Monday, 13th December, 1924, the Fife Free Press: KIRKCALDY YMCA. A record entry turned out for the MacKenzie Trophy Relay Race carried out in Edinburgh last Saturday. The teams were composed as follows:- one each from Edinburgh University Hares & Hounds, two each from Edinburgh Harriers, Edinburgh Northern Harriers, Edinburgh Southern Harriers and Falkirk Victoria Harriers and one each from Kirkcaldy YMCA Harriers, Heriot CC, Gala Harriers, Berwick & District Harriers, Stirlingshire CC and Linlithgow Harriers. The course was one of two and a half miles, and was covered once by each member of the respective teams on relay, and the finish was 500 yards of stubble to this place. Edinburgh Southern Harriers were proved winners. Kirkcaldy Harriers landed ninth of the 18 teams with a side of the following menbers:- R Biggar, P Braid, P Gourlay and J Cameron. On the whole they did very well, showing an increase of points from last time. For Lirkcaldy Biggar had the best time and P Gourlay second best. Today a five mile handicap takes place starting from the North School at 2:45 pm. The route will be round Chapel Village, finishing via Hendry Road. A large entry is expected.”

Monday, 22nd December, 1924, Dundee Courier: THISTLE CLUB RUNNERS IN FINE FORM. The first of the big inter-club runs which Dundee Thistle Harriers have arranged took place on Saturday, when Dundee Thistle, Dundee Hawkhill and Kirkcaldy YMCA met in a race over the severe cross-country course usually used by the Thistle harriers for their club championship. The race proved an easy win for T Whitton, Thistle Harriers, who finished 500 yards in front of his Thistle clubmate, A Whyte, in the excellent time of 43 minutes 52 seconds for the seven and a half miles. G Calder, Kirkcaldy, was third, with P Taylor Thistle in close attendance. In the team race, the home club had another easy win, eight of their men being in the first twelve to finish. Results:- 1. T Whitton (Thistle H); 2. A Whyte (Thistle H); 3. G Calder (Kirkcaldy); 4. P Taylor (Thistle H). Teams:- 1. Dundee Thistle Harriers; 2. Kirkcaldy YMCA; 3. Dundee Hawkhill Harriers.”

*

In 1924, then, the club was clearly in good fettle and at the end of the year, on 12th October – right at the start of the winter season, they joined the Edinburgh & District League (founded in 1924 by four Edinburgh clubs) which was the forerunner of the very successful East District League. This league consisted of races at various venues over the course of the cross-country season, and Kirkcaldy YMCA hosted the second E&D League Cross-Country race of the 1925/26 season. This may have been the first ever Cross-Country race in Fife ( although it is possible that St Andrews University had paper trail events before that). They were a strong team in the League and in 1927 former Edinburgh Harrier and now Kirkcaldy member George Sandilands donated a Silver Shield to the E&D League to be presented to the winning Club in the League for the season. This trophy is still being presented at the East District League up to the present time.

1925 started with a visit from Dundee Thistle Harriers which was well attended and was a good year for the club which tied with Gala Harriers for first place in the East District Championships. This was the first big team victory for the club even although it was shared with another club. The report in the Dundee Courier read as follows: “The Eastern District oif Scotland Cross-Country Championships run in Dundee on Saturday, was tied for by Gala Harriers and Kirkcaldy YMCA. This has never before occurred in this race, and will doubtless give rise to some controversy regarding the allocation of championship medals. A crowd of about 2000 turned out to witness the start which took place in a downpour of rain. Lord Provost High dropped the flag which sent the 130 runners up the Ancrum Road en route for the 7 1/2 miles of country which constituted the course. In the first fifty yards it was noticeable that the Dundee Thistle man, T Whitton, who for two years has run second, had snatched a lead of two yards from his nearest rivals. This lead he gradually increased and was never passed.

When the crowd, which at the finish had increased to about 3000, caught sight of Whitton entering the last quarter mile with no other runner in sight, the cheer that broke forth gave every evidence of the popularity of the Dundonian’s win. He had run his race in what we have learned to call the ‘Nurmi way’ – that is he had run with no thought of the other runners in the race but had made his own pace – every runner knows how difficult it is to do that even for a mile – for the whole course and finished a good 400 yards in front of R Biggar of Kirkcaldy YMCA.

Biggar passed R Paterson, the Edinburgh Southern flier, in the last mile and had a lead of about 100 yards on Paterson at the finish. JW Henderson, Gala Harriers, was fourth. Results:- 1. T Whitton, Dundee Thistle; 2. R Biggar, Kirkcaldy YMCA; 3. R Paterson, Edinburgh Southern. Teams:- 1 and 2 equal Gala Harriers, and Kirkcaldy YMCA 112 points each; 3. Edinburgh Northern 128 points.”

In 1928 D. Ross was the first Fifer to win a league race at Musselburgh and they made a strong bid for the team title in 1929/30 being just pipped by Edinburgh Southern Harriers.

The club had not run a team, or indeed any individual, in the National championships throughout the 1920’s. They seemed to prefer a home run on the day of the race. eg at the end of the 1928-29 season they had a New Members v Ex-Members race over 7 miles. The result was a win for W Gibb (New Member) in 42:20 from J Grant (ex-club champion) There was also a 5 miles sealed handicap for a special prize presented by President George Sandilands the following Saturday. It would have been interesting to see what the club could have done in the National.

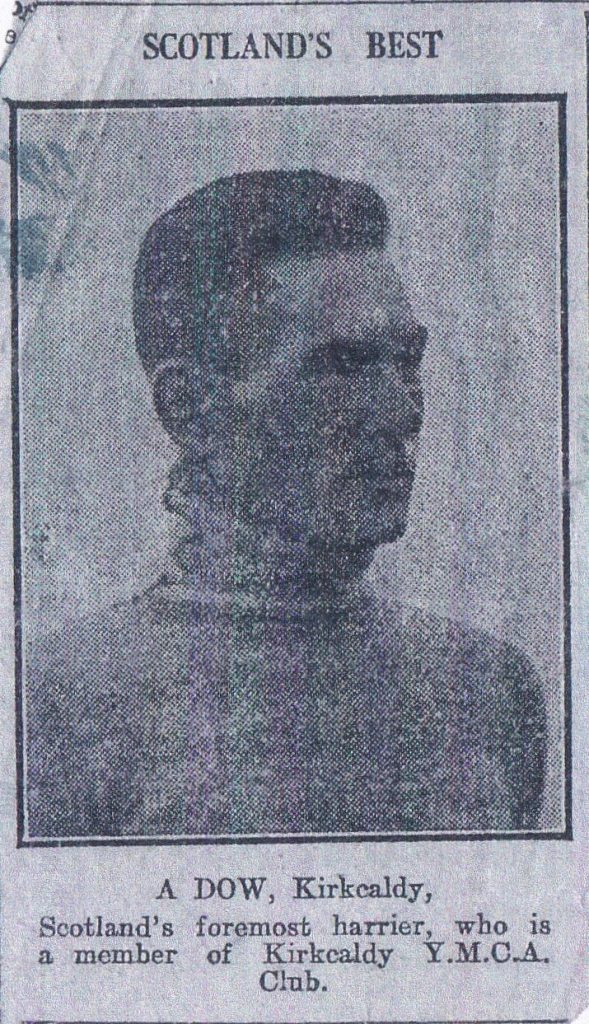

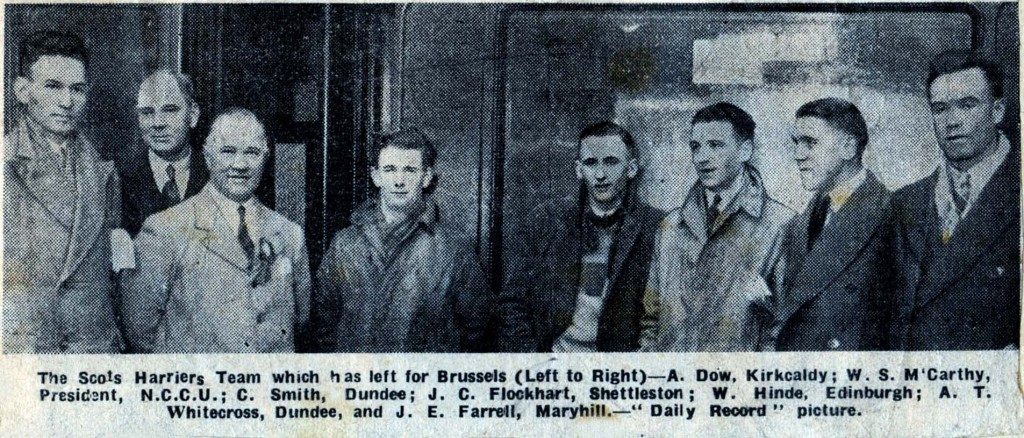

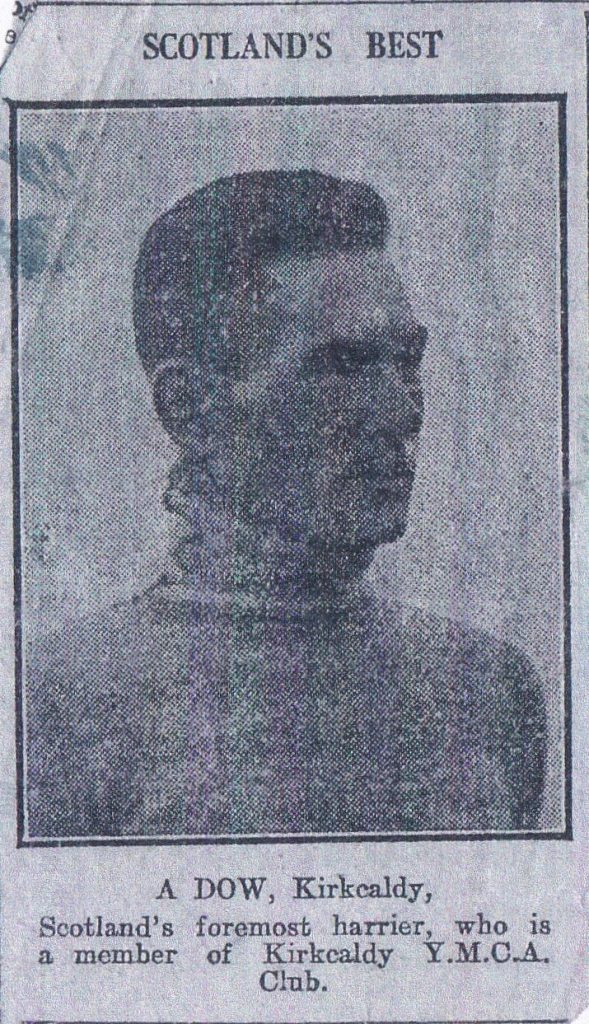

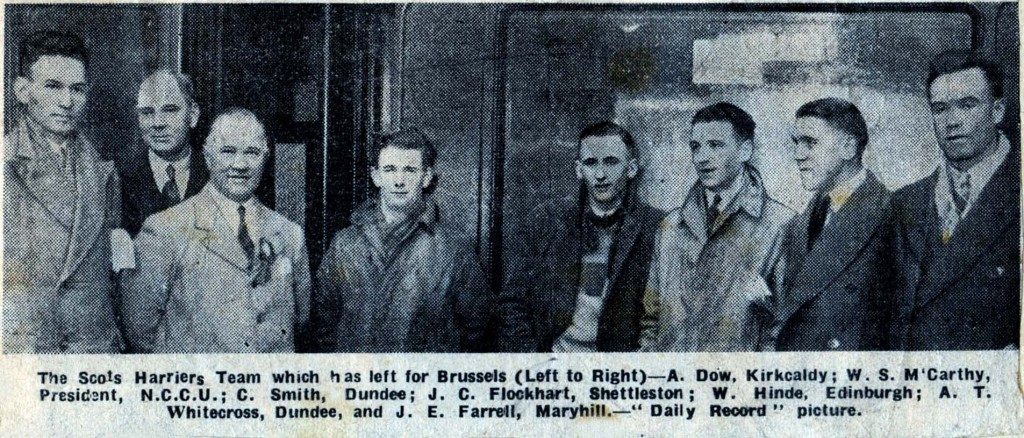

In the East District Cross-Country Championships in the 1930’s the club started well but fell away slightly as far as results were concerned – in 1930 they were second team, in 1931 they were fourth, in 1932 they were seventh and they were not in the first four despite Dow winning the race. An interesting feature of Kirkcaldy athletics at this time is the number of clubs emanating from the area. The final Edinburgh and District League of 1935 had no fewer than four such teams – Kirkcaldy YMCA was third, Kirkcaldy Eastbank was fourth, Kirkcaldy Old Boys Club was fifth and Kirkcaldy Boys Club was eighth. The top Eastbank man was Dewar who finished second to Dow in the 1934 East District Championship. There are also Press reports of a Kirkcaldy and District League – three meetings all apparently early in the winter. In the 1934-35 winter they started with the East District Relays at Musselburgh and the team consisted of Dow, Duncan Wishart and Pryde. They were again second club in the East District League in the ’34/’35 season when Alec Dow, see below, who is probably their most famous athlete, won the first race and they were second in the final, in addition to taking the 1934 East District championship title at Musselburgh. He went on to represent Scotland in five XC Internationals in the 1930s and was always in the first 3 scorers for Scotland.

The 1930’s was a a period when the YMCA movement was particularly strong in Scotland and there were many harrier clubs contesting their championships – Aberdeen, Cambuslang, Dundee, Glasgow, Hamilton, Irvine, Johnstone, Kirkcaldy, Kilmarnock, Larkhall, Motherwell, Paisley, Stevenston were the main ones. Among them all, Kirkcaldy more than held its own. Results in the championships in the decade up to the start of the war in 1939 were as follows.

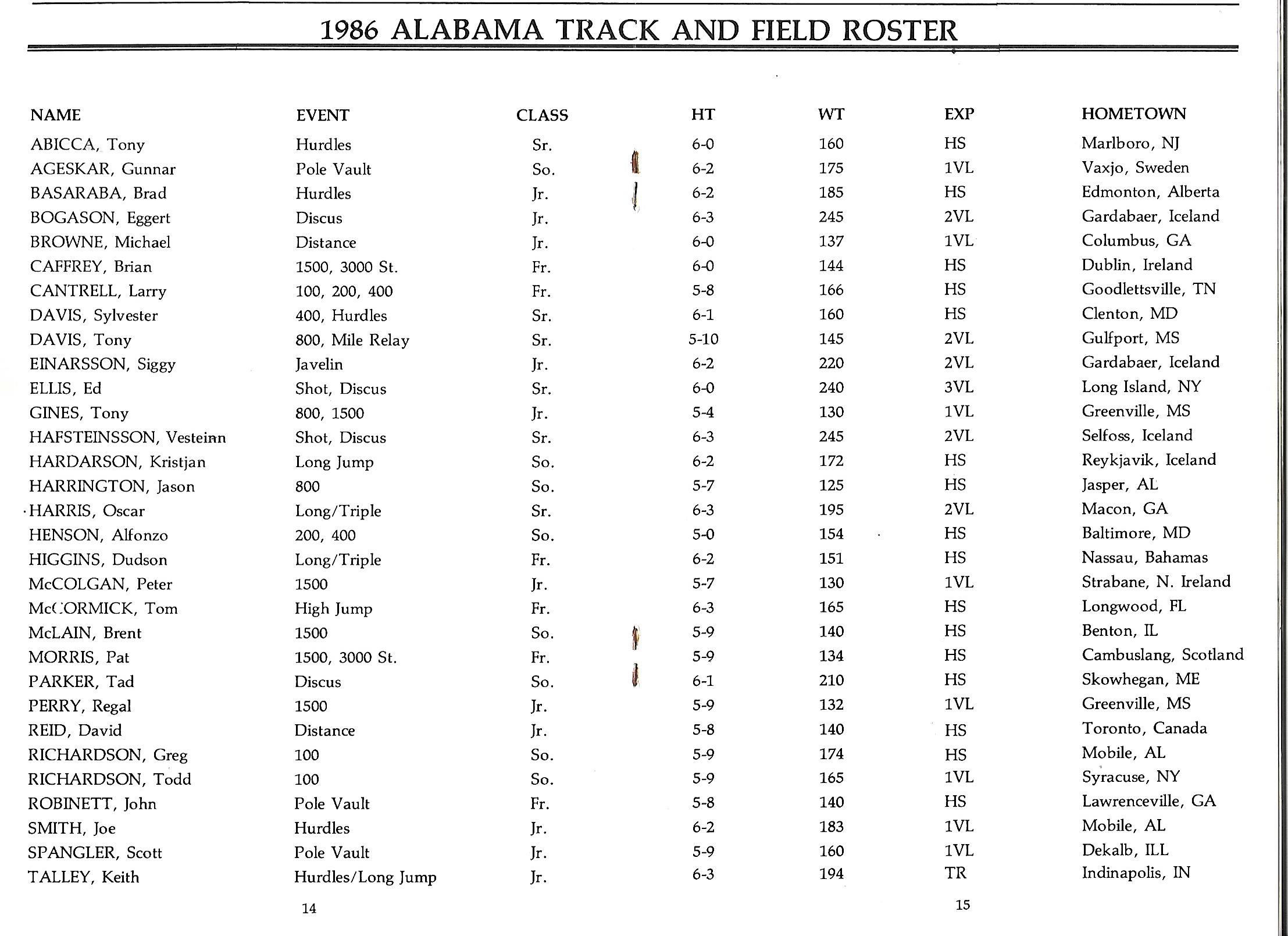

| Year |

Place |

Runners |

|---|

| 1930 |

Second |

3 D Ross/4 W Gibb/6 J Reid/16J Adie |

| 1931 |

First |

2 J Reid/6 J Adie/8 T Dewar/13 W Duncan |

| 1932 |

Fourth |

4 S Torrance/11 W Gibb/26 W McGeorge/31 A Wishart |

| 1933 |

First equal |

1 A Dow/3 A Torrance/13 W Gibb/21 J Young |

| 1934 |

Second |

1 D Pryde/2 A Wishart/14 D Stokes/20 J Peacock |

| 1935 |

Sixth |

1 A Dow/ |

| 1936 |

|

| 1937 |

Third |

10 W Riddell/14 W McGregor/18 H Nairn/20 J Peacock |

| 1938 |

Second |

7 J Peacock/9 W McGregor/11 W Dow/13 W Riddell |

Alex Dow was undoubtedly the top athlete from the club in the 1930’s . You can, and should, read the detailed profile of this outstanding athlete at this link . There is just too much to include in this account. Although he never won the National Cross-Country senior title, his best position was second in 1938, he was good enough in an era of top class endurance athletes to represent Scotland no fewer than five times in the international fixture being third in 1936 when he led the team home. Known as a cross country man, he was also a more than capable track runner and won the SAAA 10 Miles track championship in 1934. He ran in the international in 1934 (12th), 1935 (10th), 1936 (3rd), 1937 (17th) and 1938 (27th) and was a scoring runner every time. Dow was still running for the club and acting on the Committee after the war was over and is one of the many Scots whose career was completely disrupted by the War.

The message is that the club had done well during the 1930’s at both YMCA and District Championships, in both Kirkcaldy and Edinburgh & District Leagues as well as in inter-club fixtures.

The fact that YMCA clubs were more than just athletic clubs has been mentioned elsewhere on this website and the difference manifested itself in various ways. The different activities were seen by the movement and the local committees (though maybe not by some of the members of the clubs or activities competing under the banner) as a means to an end. The following advertising column appeared on Saturday 14th May, 1938, in the Fife Free Press:

“A publicity campaign is being launched with a view to attracting members, and already several attractive posters are being displayed both inside and outside the Institute. For the first time in many years Kirkcaldy YMCA is to be represented at the Scottish YMCA Golf Championship, the Eastern Section of which will be played off at Balwearie within the next few weeks. Definite date and time will be annunced shortly. The local entrants are:- Mr AA Christie, Mr WK Anderson and Mr GR Brodie.

The Harriers club continues to meet on Tuesday and Thursday evenings, at Beveridge Park, and will continue to do so during the summer. Young men desiring to join this association activity are invited to call and see the general secretary at Kirk Wynd, or to communicate with the secretary of the Harriers Club, Mr A Wishart. The finance and general committee will meet on Monday evening, when plans for the winter programme will be discussed and several other important decisions will be taken.

The YMCA Library is being re-organised, and several new and attractive volumes will be added in the religious, fiction and general interest categories. The general secretary etends an invitation to young men who are interested in any of the threefold aspects of YMCA work, to call and have a talk with him any evening in his office at the Institute, Kirk Wynd.

“The Young Men’s Christian Association,” says Mr Basil Matthews, the noted author and Christian scholar, ” ought to be the striking force of the Christian revolution.” The YMCA has almost two million members in 57 countries. Join in and swell the ranks of this mighty movement.”

It was quite a range of activities – golf, running, library and an Institute where many other interests could be pursued. The club had been very active in the 20’s and 30’s but this activity was brought to a temporary standstill when the 1939-45 war broke out. For a look back at this period through the eyes of the runners, read this article, published by the ‘Fife Leader’ .

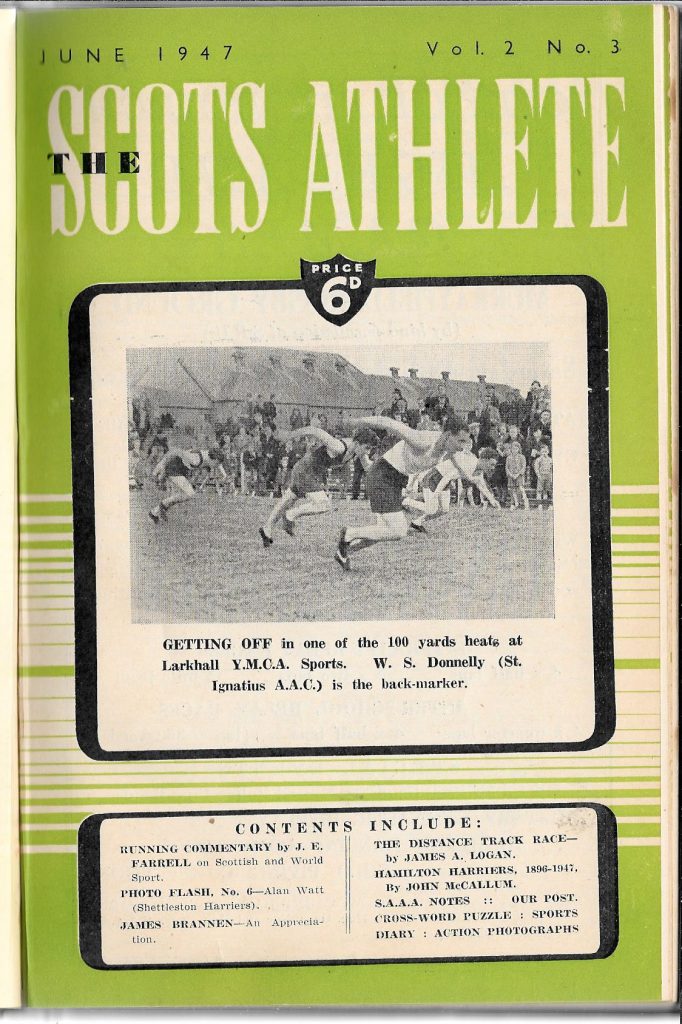

Athletics had been put on a war-time footing for the duration and so it was possible to start up more quickly than had been possible after the first war when the sport had stopped completely. The East District League started up again in 1946 and Kirkcaldy YMCA was one of the teams to host a fixture: beaten by Dundee Thistle in the first match, in the second match at Kirkcaldy, they won thanks to a great team effort from Preston (3), Clark (4), Duncan (7) and Peacock (8) who were all in the first eight, with support from Bell 18th and Dow (19th). The presence of Dow would inspire them all. They competed frequently in this period and at the start of the 1947-48 cross-country season they turned out in several relays – Emmet Farrell in the ‘Scots Athlete’ magazine of December 1947 took a look at the relay season beginning with the YMCA Relays: “Motherwell, reinforced by the inclusion of Olympic mile possible Jas. Fleming, not long back from overseas, had a sound win over Kirkcaldy YMCA who included the well-known ex-ten mile champion and internationalist Alex Dow.” The East District Relays were held at the Edinburgh University King’s Buildings trail on 6th December 1947, and the Kirkcaldy squad “finished 3rd thanks to a splendid run by the diminutive J Preston.” The team was W Grieve (17:45), A Dow (18:34), J Ritchie (18:10) and J Preston (17:23) Preston had the fifth fastest time of the day and Grieve had 13th quickest. The East District Junior Championship was held at Galashiels on th February 1948 and the team of six was second behind Edinburgh Southern Harriers. The runners were J Preston 6th, J Ritchie 10th, G Rennie 13th, WE Duncan 14th, W Grieve 15th, J Peacock 20th. Team totals were 1. ESH 63 points; 2nd KYMCA 78 pts; 3. Edinburgh University 79 points.

There had been no team from Kirkcaldy in the first (1946-47) national cross country championships after the war, but in the second championships, held on 6th March 1948 at Ayr Racecourse the Youths team won their championship. Runners on the day were W Grieve (3rd), J Duncan (15th), A Motion (17th), J Beaton (19th) giving a team total of 53 points against St Modan’s 88. Eighteen teams teams ran in the race. There was good back up for the team from A Millar and J Dewar who finished 45th and 88th. For two of the runners it was their second team medal of the season – earlier in the year the team had been second in the East District Championships behind Edinburgh Southern Harriers with the counters being J Preston (6th), J Ritchie (10th), G Rennie (13th), WE Duncan (14th), W Grieve (15th) and J Peacock (20th) and they also had men placed 21st, 52nd and 56th. The club undoubtedly had the runners.

Between the District and National championships, the race that had the headlines locally was the Scottish YMCA Championships in February 1948 when W Grieve won the Junior Championship. I quote from the Fifeshire Advertiser of Saturday 28th February, 1948:

“W Grieve of Kirkcaldy ran the greatest race of his career when he won the Scottish YMCA Championships in Edinburgh on Saturday last when he led the Junior team to victory. The two championships, Junior and Senior, were run from Dr Guthrie’s School. The juniors, covering a course of three miles, were sent on their journey 15 minutes before the seniors who covered the course in two laps. When the juniors came into view, W Grieve was leading by about four yards but, with more stamina than his challenger ran out an easy winner. His team mates followed closely behind, six men finishing in the first sixteen. Team placings:- 1 W Grieve; 3 J Duncan; 7 J Renton. Total 11 pts. 2. Johnstone YMCA 26 pts; 3. Motherwell YMCA 36 pts. In the senior event, the club was represented by a complete new team, as Kirkcady won this event last year and were not eligible to compete with the same team this year. Motherwell YMCA with men of the calibre of Alex Fleming, G Wood and Willie Sommerville counting 1, 2, and 3, gave little hope of any other club lowering Motherwell’s colours. However, the Kirkcaldy club did remarkably well to finish third. Result:- 1. Motherwell 24 pts; 2. Glasgow YMCA 41 pts; 3. Kirkcaldy YMCA 44 pts. Team:- 5th G Rennie, 6th P Husband, 16th J Bell, 17th G Millar. ”

They were however very active in the Edinburgh and District League with fairly strong teams turning out over the winter. Into winter 1948-49 and in the Kingsway Relay on 16th October the team was 8th of the 23 competing. They were also of course still competing in the League and the race report reads “Results:- 1. Edinburgh University 46 points; 2. Edinburgh Southern 87 pts; 3. Rosyth Caledonian 96 pts; 4. Kirkcaldy YMCA 117 pts. P Husband Kirkcaldy YMCA finished 5th, J Preston 7th, W Dunn 14th, which was good packing but the tail was weak which accounted for the club’s position and it is anticipated that an improvement will be shown in the next race. Today the club will run over the McKenzie relay trophy course of two and a half miles.” (Report from the Fife Free Press of 6th November, 1948)

The second East District League Match took place at Kirkcaldy on 4th December, ’48, with a team of W Duncan, D Beveridge, P Husband and J Preston and when the times were looked at, Preston was 7th fastest and Beveridge was 8th. The East District Junior Championships were held on 5th January 1950 and the YM were second team with a total of ten runners running. The scoring team was Husband 4th, Grieve 6th, W Duncan 12th, Gordon 18th, Rennie 19th and Beveridge 25th. The back-up runners were Ritchie, Peacock, McCallum and Fraser.

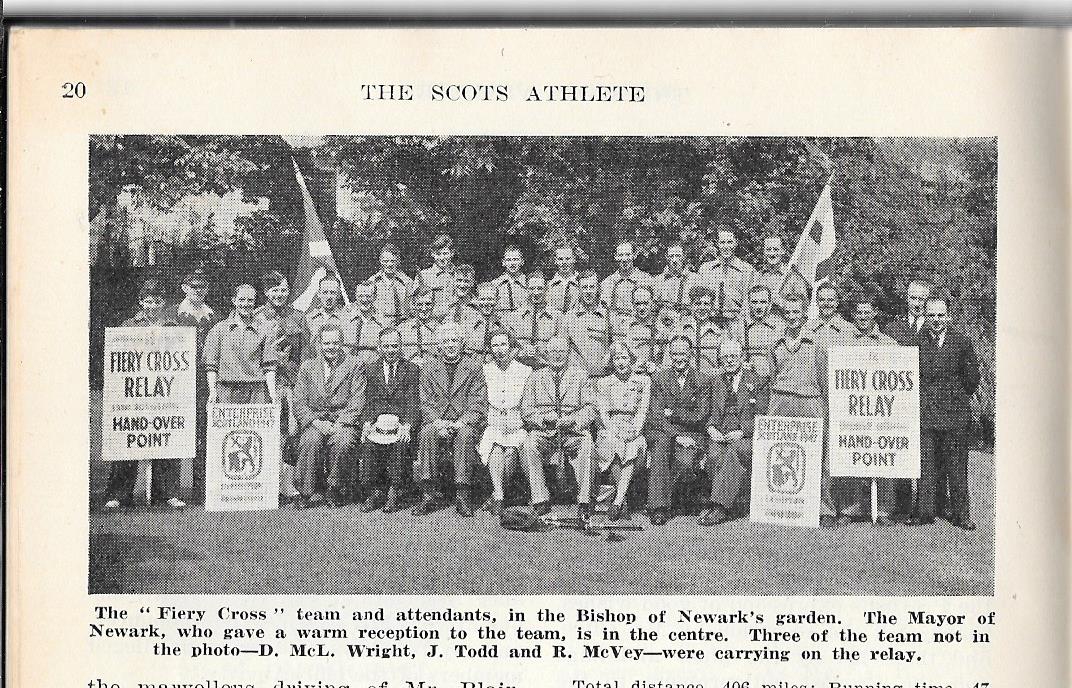

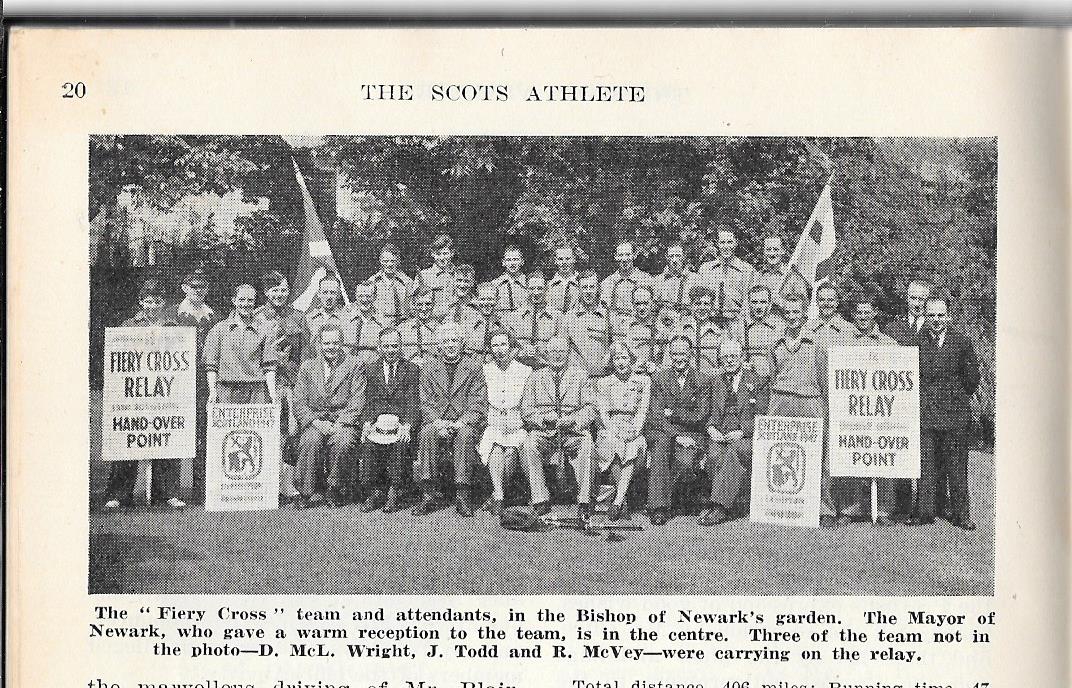

Valuable publicity was gained for the club from the participation of A Thomson in the Fiery Cross Relay from Edinburgh to London prior to the 1948 Olympic Games. A group of Scottish runners led by Dunky Wright and Donald Macnab Robertson carried their crosses for various distances with each runner finishing his stint by handing the cross to the Mayor of the city where he ended his stint. In Thomson’s case he performed the handover in a stadum filled with 6000 spectators to be received by the Mayor of Doncaster and ran, in total, 21 1/2 miles.. You will note that the men are holding their crosses upside down so that they look like wee swords. At the start of the first stage, the torches heldd the right way up would not light,so they were turned upside down – and the lit first time and the photographs of the start have the runners leaving the Esplanade at the Castle bearing aloft what look like swords.

Thomson was not the only useful road runner in the club at the time: WE Duncan was third in the Perth to Dundee Race on 26th August 1950 when it was run in rain with thuder and flashes of lightning while the race was going on for the men to endure. His time was 2:10:25 – exactly 60 seconds behind second placed Arbuckle of Monkland. Then there was J Bell who ran in the Round the City marathon run in Edinburgh as part of the Highland Games on 2nd February, 1950. He finished 10th in 3:10:51.

The club was 6th in the East District Relays in November 1949 (Beveridge, Gordon, W Duncan, Husband). On 21st November 1949, the club felt strong enough to enter a team in their first ever Edinburgh to Glasgow eight stage relay where they finished 13th of the 22 clubs participating. Their runners, in order, were D Beveridge, J Peacock, WE Duncan, RC Hewson, G Millar, P Husband, A Harrower and G Gordon. On 18th December they travelled to Rosyth for an inter-club with the Caledonia club. They followed this up with a team of Preston, Husband, Beveridge, Grieve, Rennie and Duncan in the Dundee Thistle Jubilee Relay over 4 miles: it was an unusual format with two runners running each lap. The note in the Free Press finished by saying that the train to Dundee would leave at 11:35 am – a wee reminder to us all that getting to the races took a bit of organisation even in 1949. On 4th February 1950 the club team was third in the East District championships with Rennie 6th, Duncan 13th, Gordon 22nd, Husband 32nd, Beveridge 33rd, and Peacock 35th being the main men, with support from Gray, Harrower, Millar, Taylor and Hewson. They certainly had strength in depth and competition for places. Towards the end of 1950, the club was fifth in the Kingsway Relay, 5th team in the first League Race (with both Duncans running: J Duncan on the third stage and W Duncan fourth) and on 4th November they were 12th in the District Relay and the Edinburgh to Glasgow came on the third Saturday. The club race for the Hon President’s Prize was on 6th January and was won by AB Thomson from WE Duncan and G Mortimer.

In the Eastern District Championships on 3rd February, the club was among the prizewinners again when the Senior team finished third behind Edinburgh University and Edinburgh Southern. Their men were W Duncan 10th, G Mortimer 12th, J Duncan 13th, P Husband 16th, A Beveridge 32nd and G Bell 40th. However when it came to the National Championship on 3rd March, the only runners from the club was A Rennie in 41st place in the junior with no other senior, junior or youth running. The winter season was not yet at an end: the club race over ten miles was held on the last Saturday in March and was won by G Mortimer in 63 min – the report commented that ‘he won very readily and is definitely a winning prospect’. Three of the more established club men were running later in the week in the YMCA International Championship in Manchester. P Husband, W Duncan and G Rennie were the men in question.

This was a sign of the times though – several other well established clubs did not turn out their best teams, or in fact turn out any teams consistently in District or national championships. Clubs such as the two main teams in Greenock, for instance, did not regularly turn out in National championships despite having some outstanding talent to draw on, and they were not alone in this. For Kirkcaldy, the journey may have been a key factor – were they to go by train it would have meant at least one change of train in each direction. Nevertheless, Kirkcaldy, for all their apparent strength in the 1940’s and early 50’s did not turn out any teams in the 1949 national and only one runner (W Grieve in the Junior race) in 1950. Nevertheless, it was into the 1950’s with some optimism as far as the distance men were concerned. Teams were out in almost every race, there were often ten men in a race where only six were to score, and they had entries many of the road races organised by the Scottish Marathon Club which, formed in 1944, pre-dated the English Road Runners Club.

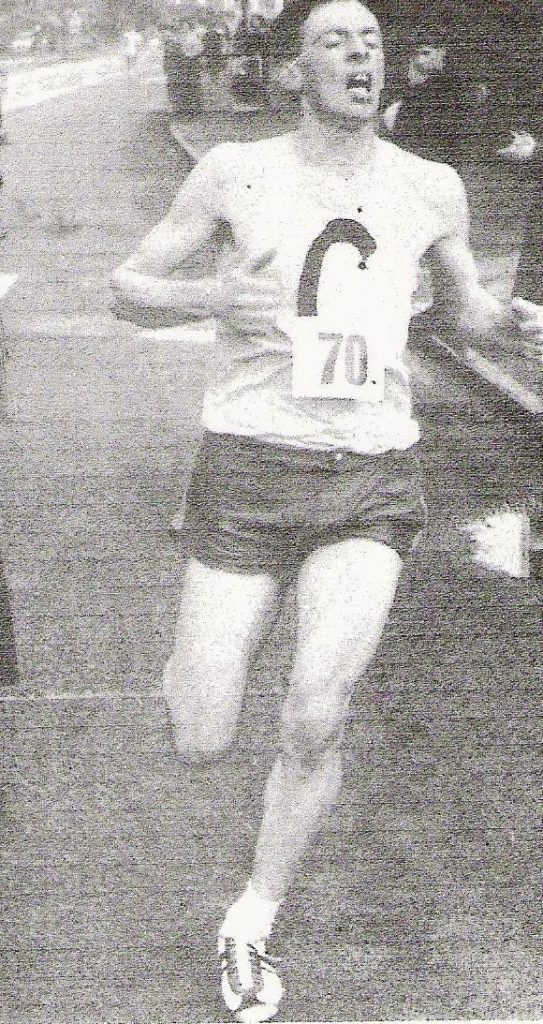

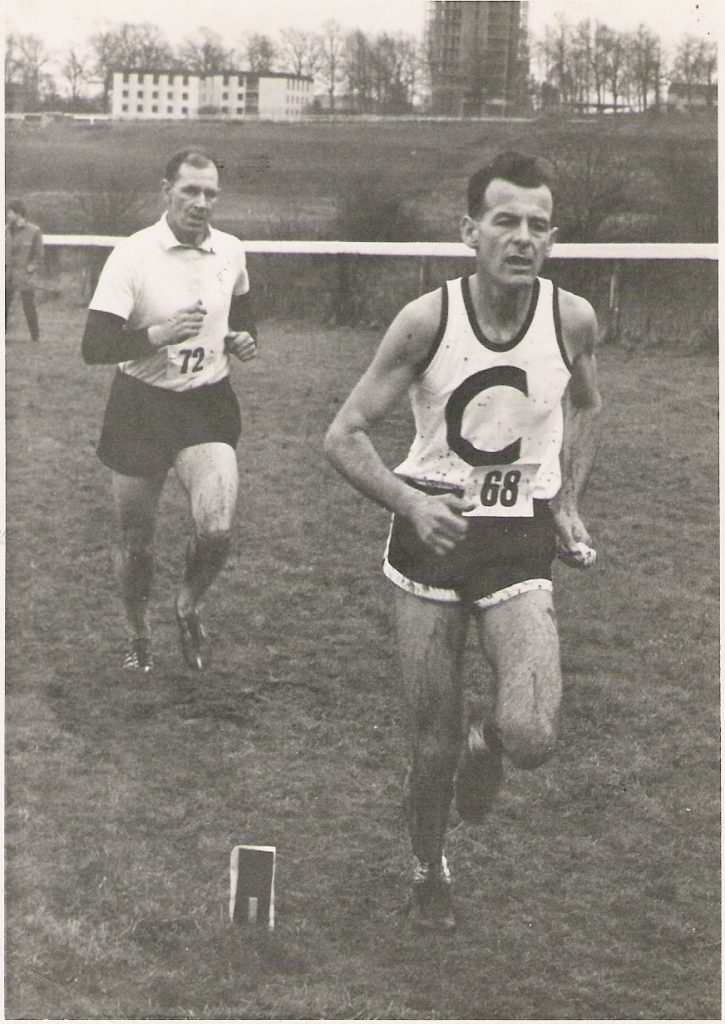

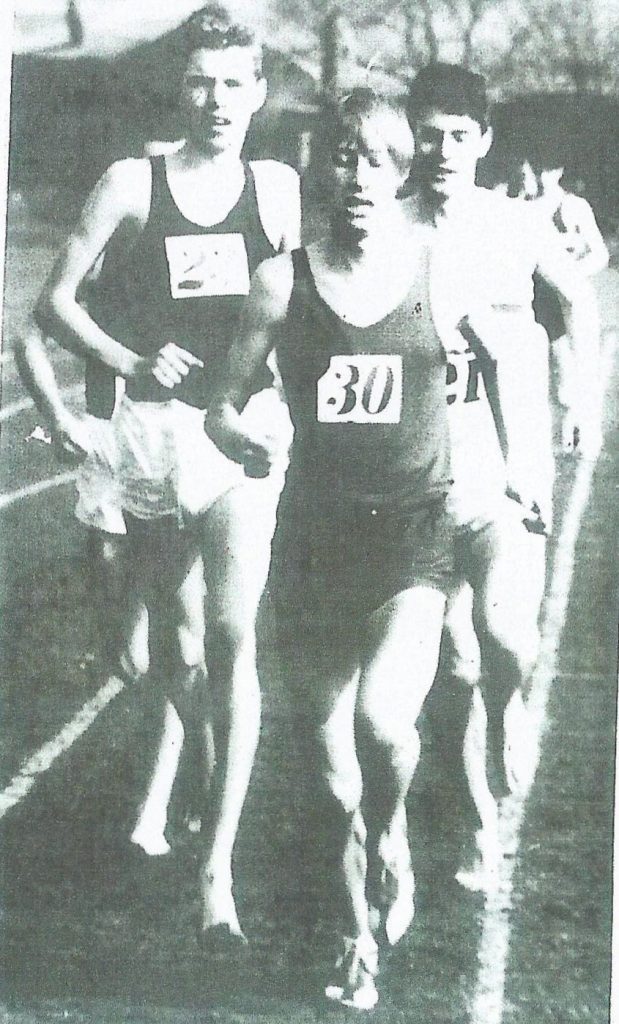

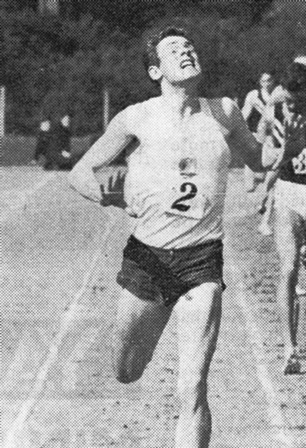

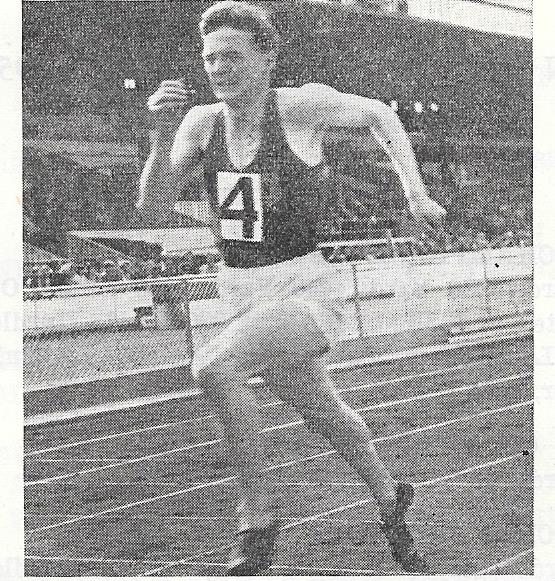

Gerry Mortimer (24)

KIRKCALDY YMCA IN THE 1950’s

Any club that is successful needs a good committee and the indications are that for the first half of the decade the club had a good group of administrators looking after their affairs. At the meeting in February 1950, the following were elected as the main office-bearers: Hon. President Mr A Wishart; President J Peacock; Hon. Vice Presidents A Thomson, D Ross, A Dow, D Baldie, H Stoddart and Dr Wishart; Vice-President W Duncan; Captain P Husband; Vice-captain D Beveridge; hon secretary RC Hewson; Assistant secretary G Duncan; hon treasurer R Kirk; General Committee G Mortimer, T Burns, G Dewar, A Gibson and G Gordon; ….. Trainer T Burns.

Competitively the 1950’s started well for the club with good solid performances over the country, on the road and on the track. A brief look at the local track meetings is enlightening. Inter-clubs were, a feature of a time when there were not too many competitions for the athletes and on 29th May, 1950, Kirkcaldy hosted Watsonians from Edinburgh. It was a restricted programme but the top placings for the home club were as follows:

100 yards: 2nd J Dewar; 440 yards: 3rd R Curtis; 880 yards: 2nd G Mortimer; Mile: 1st G Mortimer, 3rd P Husband; High Jump: 1st J Hughes; Long Jump: 1st J Hughes; Hop, step and jump: 1st J Hughes, 2nd J Beveridge; Shot: 3rd A Gibson; Mile Medley Relay: 1st Kirkcaldy YMCA. They had covered every event and only lost to Watsonians by five points (27 to 32).

They also took part in local open meetings such as the one organised by the Scottish Industrial Sports Association at Stark’s Park in late June where J Dewar won the 100, 220 and 440 yards as well as being second in the high jump. Ian Chrystal won the 880 yards and was third in the Mile; P Husband mirrored that when he won the Mile but was third in the 880 and finished up by winning the obstacle race.

They also turned out in strength at the Dundee North End Sports on 8th July where all the other clubs from the North East were competing in what were mainly handicap events. Principal Kirkcaldy performances were J Dewar’s triple victories in the 100, 220 and 440 yards; WE Duncan winning the 12 mile Road Race Handicap with J Peacock third; and D Beveridge winning the 2 miles Open Handicap from a mark of 190 yards.

The club was clearly in fine form with good athletes across the board. One of the main events for them of course was the YMCA national championships. These were held in the middle of May every year and Kirkcaldy runners were successful at distances from 100 yards to two miles. The best performers over the period were W Ewing (who won the Youths 100 yards in both 1954 and 1955, Junior 100 and 220 in 1957 and the senior 100 and 220 yards in 1958), G Mortimer (who won the 2 Miles in 1953 and 1954) and there were Junior sprint doubles in 1955 (J Dewar) and 1956 (RR Mullen).

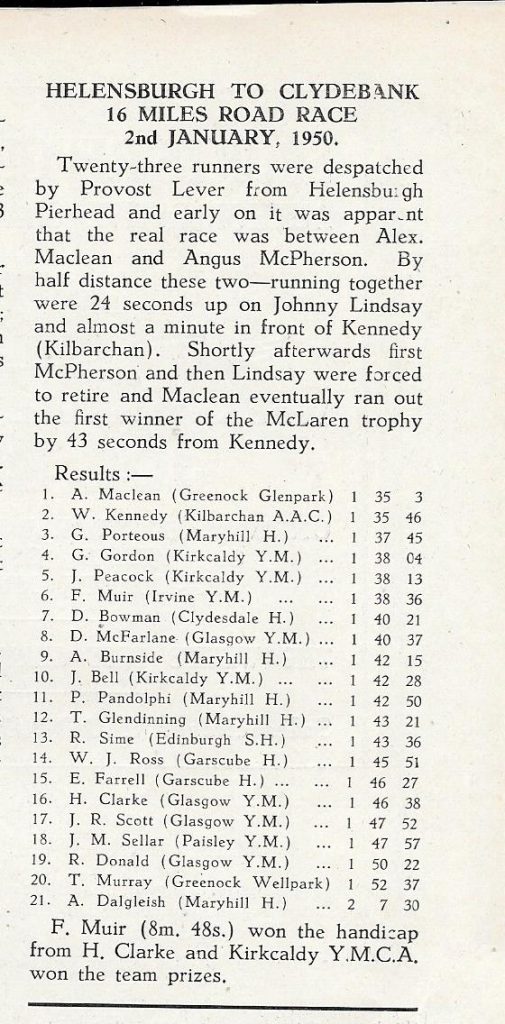

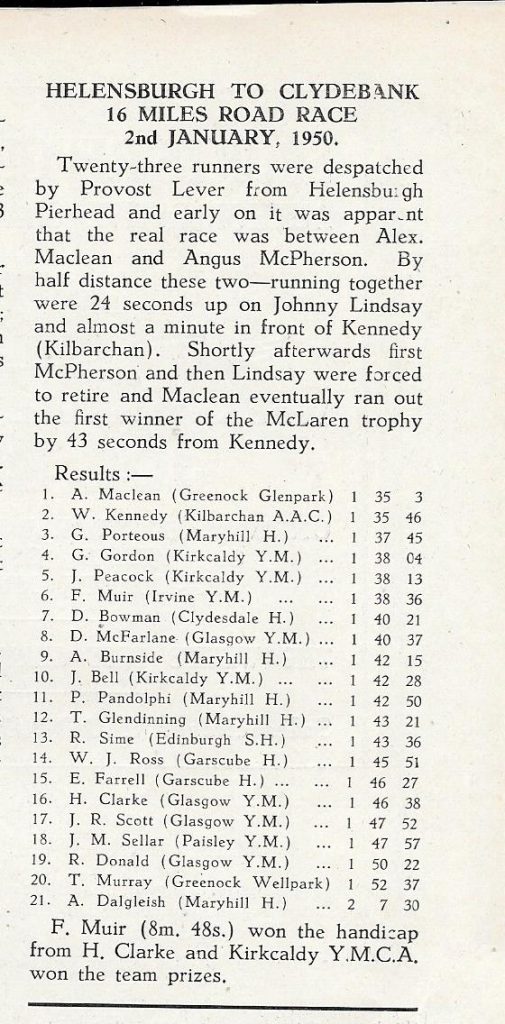

Arguably the best team performance by the club, in 1950 at least, was the victory in the first ever 16 miles Helensburgh to Clydebank Road race on 7th January 1950. The report in the Courier read: “On January 2nd in the inaugural Clydebank to Helensburgh 16 mile road race sponsored by the Dunbartonshire AAA, Kirkcaldy YMCA won the team race by two points from the famous Maryhill Harriers. The team’s points were made up as follows:- 2nd G Gordon, 3rd J Peacock, 6th J Bell. In the individual race the team were placed as follows:- 4th G Gordon, 5th J Peacock, 8th J Bell. The club’s congratulations must go to these runners on this fine feat and also to J Chrystal for his fine running on December 31st in the Edinburgh Eastern Harriers Open Christmas Handicap in which, out of a field of 59, Ian was placed 3rd. On Saturday January 7th, the club will hold its Hon President’s Prize, decided on a handicap basis on a 5 mile road course through Chapel. Following this, the club will travel to Edinburgh on January 14th for the second League match.”

The win in the Helensburgh to Clydebank (the paper had the direction wrong!) was indeed significant with a victory over the celebrated Maryhill after the long journey from Kirkcaldy before the event. The difference between the team placings and the actual placings is because the practice was to exclude individual entries from the team places.

The apparent discrepancy in places is because, under the rules operating at the time, runners not in a team were excluded from the calculations for the team awards.

The club seemed to have developed a taste for the longer distances and J Bell ran the SAAA Marathon in 1951 (23rd June) and finished third to win a senior man’s championship medal with his time of 2:50:38. On 25th August came another team win in a long road race when they won the team race in the Perth to Dundee event. J Bell was eighth in 2:13:49, WE Duncan was 11th in 2:18:05, P Husband was 13th in 2:22:17 and J Peacock was 15th in 2:26:04. The result was a victory with 32 points to the Glasgow YMCA’s 42 points.

Start of Perth to Dundee Race in 1951

Two months later and Husband came down a few distances to run the last leg in the Scottish YMCA Relay championships: the team of Mortimer, Beveridge, Corroon and Husband was third with Mortimer being third fastest runner on the day. That was in

January and they started the winter on 1950-51 with an excellent 5th place from 20 teams competing in the Dundee Kingsway Relay where they had two teams competing. They were a very good road running squad.

How about over the country in 1950? Starting on 17th February, 1950, with the Scottish YMCA Championships, the report in the Fife Free Press said: “This year, for the first time since 1931, the Scottish YMCA National Cross Country Championships will be held in Kirkcaldy. In these championships Kirkcaldy YMCA Harriers have a fine record, having won twice in three years and being runners-up on the other occasion. These performances may be regarded as particularly meritorious in view of the fact that every time a YMCA Harriers club wins, it must find fresh runners for the ensuing year. Kirkcaldy Harriers have this year an undoubted chance despite the fact that they were the winning team last year at Motherwell, when the counting four of the winning team were:- G Rennie, P Husband, W Grieve and D Beveridge. With the exception of W Grieve, these runners are competing this year in the individual. The first nine in the individual represent Scotland in the international YMCA Cross-Country Race at Manchester in April, and Kirkcaldy hope to have several members in the team as they did last year.”

Several of the club did represent Scotland in the YMCA International at Manchester in April. With WE Duncan of the club acting as team captain, the first Scottish finisher was P Husband who was one of the counting six. WE Duncan and G Rennie were unlucky in suffering ‘stitches’ during the race and ran below form. Nevertheless it was a credit for the club to have so many in action. Remember that the Scottish championships had such as Aberdeen YMCA, Bellshill, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Irvine, Johnstone, Kirkcaldy, Larkhall, Motherwell, Paisley and others competing. It was not an easy vest to get.

The disappointing thing however is that they were not competing at national level despite having the talent and numbers to do so. In the national at Hamilton on 4th March only one man was representing the club, and that was W Grieve who was seventh in the Junior race – one place ahead of John Stevenson of Wellpark who was a very good runner indeed, and one place behind the leading Victoria Park AAC man. The story had been the same in the East District championships on 4th February when Grieve had been their only representative.

Over the winter season 1950-51 they did well. The club record of running in the East District Relays was a better one – for the first half of the decade at least.

| Year |

Team Position |

Runners |

|---|

| 1950/51 |

12th |

Hewson/ W Duncan/ Davies/ Mortimer |

| 1951/52 |

17th |

Mortimer/Mitchell/Thomson/Hewson |

| 1952/53 |

12th |

Husband/W Duncan/Kay/Mortimer |

| 1953/54 |

16th |

Husband/Renton/Kay/Mortimer |

| 1954/55 |

No Team |

– |

They turned out eight men in November 1950’s E-G relay, then finished third team in the East District championships on 3rd February (W Duncan, G Mortimer, J Duncan, P Husband, A Beveridge and G Bell). But not a man in the SCCU Championships exactly one month later.

They were still running well on the track in the early 1950’s. For example on 9th June 1951, there was an item in the Fife Free Press which ran: “Kirkcaldy YMCA Harriers did very well at the Open Sports Meeting held by Edinburgh Milton Wrestling Club at New Meadowbank on Saturday. Members gained prizes at distances ranging from the 100 yards sprint to the 12 miles road race. In the 100 yards J Dewar put in a strong finish to finsih third. A spectacular success was gained by G Mortimer in the Open Mile. Running from the second backmark of 75 yards, he gradually caught his field and finished very strongly to win by 10 yards in the fast time of 4 min 21 sec. Another first prize was gained by P Husband in the 12 mile road race where he finished first beating that well-known road runner A Arbuckle, Monkland Harriers, by 50 yards. A very encouraging sign for a runner who is attempting road running for the first time.”

The Scottish YMCA Championships were held in 1953 on 16th May, and it was a good day for Kircaldy YM in the Two Miles where G Mortimer won the Two miles in 9:47 and the club won the team race with 12 points. Mortimer also won the Two Miles in the following year, 22nd May, when his time was 9 minutes 77 seconds and he was one of only two club runners to win – the other being E Ewing in the Youths 100 yards.

While working hard at home and in the local area, they did not have a single individual entered for the major Scottish cross-country championship in 1950, 51. 52, 53, 54, 55, or 56. In 1957 there were 2 Youths (P Husband and W Smith). Things started to look up in 1958 when there was a single senior (CW Foley), but a whole Youths team which just missed out on the awards by being fourth team. This consisted of J Cooper 19th, A Milton 39, J Edmunds 68 and was led home by J Linaker in second place. The following year Linaker ran in the colours of Pitreavie AAC in the same race. He also won the Junior Mile in the Scottish YMCA Track Championships later in 1958. It is an interesting sign of the times to see how his running for the YMCA came about.

At the time when Pitreavie AAC was formed, there were separate associations for Track and Cross-Country. For some reason Pitreavie AAC registered with SAAA but not SCCU. So although John (with Claude Foley and Alan Milton) was First Claim with Pitreavie it was only for track events, so he ran cross-country for Kirkcaldy YMCA H until Pitreavie registered with the SCCU in 1958. He was not alone in this – another similar case that comes to mind was that of George Jackson who ran for St Modans AAC as well as Forth Valley. However, the YMCA track championships were serious affairs with nine or ten clubs competing and international runners like Bert McKay and Andy Brown of Motherwell YMCA turned out in them. Top competitor of them all, though, had to be DK Gracie of Larkhall YM who was Scottish and British internationalist and record breaker over the 440 hurdles and who regularly – even at the top of his form – won two sprints at these championships.

On the road the major team event for any club had to be the Edinburgh to Glasgow 8 stage relay and after their first venture into the race in 1949, they ran in it in 1950 (15th), 1951 (20th), 1952 (16th) and 1953 (20th). These were very good solid runs against all of the best clubs in the country and they finished ahead of some good opposition.

Apart from the poor turnout in the national – by no means peculiar to Kirkcaldy YMCA at this point – the club performances fell away in the second half of the 1950’s Note their performances in the East District Championships:

| Year |

Position |

Team |

|---|

| 1954/55 |

No Team |

– |

| 1955/56 |

No Team |

– |

| 1956/57 |

No Team |

P Husband 26/W Smith 58 |

| 57/58 |

Not in first three |

| 58/59 |

Not in first three |

| 59/60 |

incomplete team |

P Husband 59/J Cooper 61/J Edmonds 69/W Waddell 71/J McKenzie 79 |

| 60/61 |

incomplete team |

Cooper 39/Edmonds 70/Rennie 76 |

Also in the late 50’s, Andy Brown, junior, won the Scottish YMCA cross-country championship in February, 1954, and only one Kirkcaldy man made the team for the international, P Husband who had led the team home in 1950. It was a time when the organisation was leaving the YMCA building in Kirk Wynd and moving to the new premises in Valley Gardens with a period of suspended animation between the closing of one building and the opening of the other – except for the Harriers who had a season’s commitments to fulfil.

On the track, the new ‘stadium’ opened in Dundee on 5th June, 1954, with lots of star names – eg Joe McGhee, RAF and Shettleston won the 13 miles road race, Donnie McDonald of Garscune Harriers, Pat Devine of the Q club and many others turned out- but there were some from the Kirkcaldy YMCA present. In the men’s open 100 yards, A Gibson won his heat and was second in the final, in the 220 yards open handicap J Dewar won his heat but was unplaced in the final, W Ewing was third in the Youths 440 yards, and the Relay team won from Dundee AAC. It was not a bad start to the season. Then at the North End Sports on 19th July, there were some good performances by the club – J Dewar won the 100 yards for senior men and W Ewing was third in the Youths 220 yards, and that was it. In contrast to the 1950 meeting, there was a big group of athletes from Aberdeen and another from Perth and, in addition, the Hawkhill team was particularly strong at the time. The reality was that at this point, the club which was not as strong as it had been at the start of the decade. eg the last appearance in the Edinburgh to Glasgow was in 1954. Gerry Mortimer resigned from the club and was runnning for Edinburgh Eastern Harriers at the start of winter 1956/57 in the Kingsway Relay in Dundee. He had moved house to Edinburgh and went on to have a good career as a runner there. He even had a special trophy made for him after he finished second in the East District Three Miles (50, 51 and 52). Interestingly his son, Ken, was also a runner, both loved the Edinburgh to Glasgow relay and between them they ran every stage in the race with a combined best time of about 3 hours 48 min – remarkable.

Individually the marathon men were doing quite well. In 1952, the preview for the race in the Fife Free Press for 2nd August read:

“The Scottish Marathon Championship over a course of 26 miles 385 yards from Perth to Dundee has attracted a good entry this year, and once more contestants have come forward from Kirkcaldy YMCA Harriers. This year three entries have been made in the names of J Bell, P Husband, and J Peacock. The first named will find no difficulty in running prominently in this race as the veteran has finished fourth on several occasions. P Husband and J Peacock are novices at this longest of all races, but have run well in former years in races approaching the marathon race in distance. In this respect of entries for the marathon championship Kirkcaldy YMCA Harriers may claim to be unique as there will be very few clubs in Scotland putting forward two entries far less three.”

At the finish, J Bell was tenth in the event in 2:59:28 with J Peacock thirteenth in 3:07:27, and in 1953 Bell was again tenth, this time in 2:58:11, and Peacock was again thirteenth in 3:03:18. But the club as a whole was not running or racing as well over the shorter distances as it had been and it was the 1960’s before the upturn started to take place.

Into the 1960’s

Cross-country first. In contrast to most of the 1950’s the club turned out several very good cross-country teams throughout the 1960’s – particularly in the Youths (Under 17) and Boys (Under 15) age groups. Following on from the Youths and Boys team results at the national in 1958 and 1959 the cross-country teams did very well. These are noted in the table below. First team in any category is the U17’s, second team is the U15’s. (ie Y 1st/B 1st)

| Year |

East League |

East District |

National |

Comments |

|---|

| 1960-61 |

1st/1st |

1st/3rd |

-/1st |

Good work by both teams with Under 17's having three firsts |

| 1961-62 |

1st/1st |

2nd/1st |

3rd/3rd |

3 team first places of a possible 6 |

| 1962-63 |

1st/- |

1st/- |

1st/- |

League/District/National wins for the U17's |

| 1963-64 |

-/- |

3rd/3rd |

3rd/- |

– |

| 1967-68 |

-/1st |

1st/- |

-/3rd |

| 1968-69 |

1st/- |

|

| 1969-70 |

1st/- |

2nd/- |

|

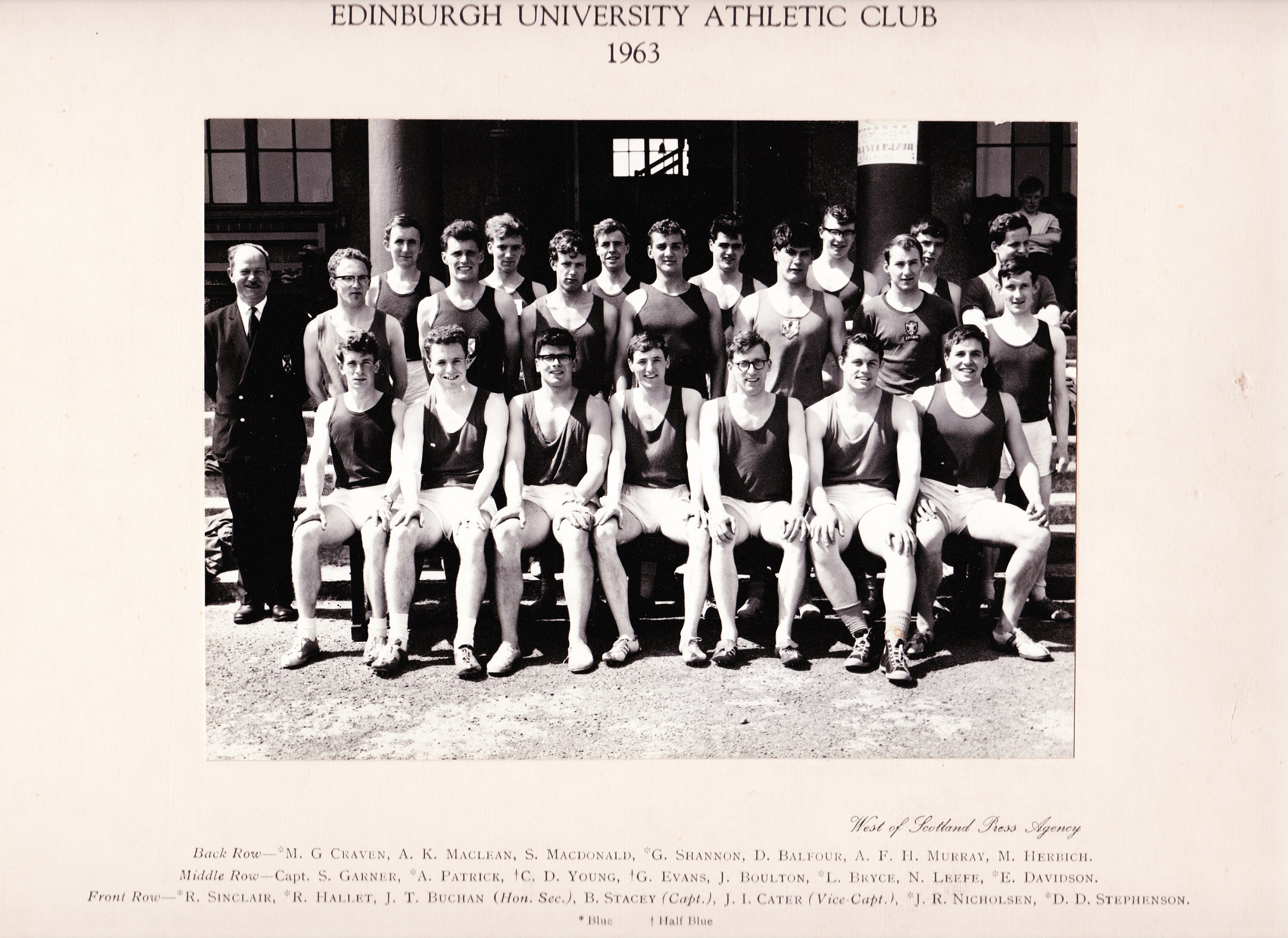

There is a copy of the programme for the National Cross-Country Championships of 1963 where you can see the relative strengths of the various age groups at the time to be seen at;

http://salroadrunningandcrosscountrymedalists.co.uk/Archive/Cross%20Country/National%20XC/Programmes/1960s/National%201962-3.pdf

The count is 14 Boys, 14 Youths, 5 Juniors and 1 Senior. You will also note that the club uniform had changed from the one worn by Gerry Mortimer in the picture above to white with gold band.

On the track, the club had men forward in the District Championships, they had inter-club fixtures and of course the club championships continued to exercise the club members. Good as the cross-country men were, the track men did not live up to these standards – or not in numbers. Success was limited too in the YMCA Championships, M Lockhart won the Youths 1 Mile in 1960, WR Fleming won the senior mile in 1961, and again in 1962; D Linton won the Junior 100 and 220 yards double (10.8 and 24.6) and D Whitehill won the Youths shot putt in 1964. It was a time in YM athletics when the Motherwell team was crushing all before it in the senior distance events – in 1964, Ian McCafferty had a superb double and in 1966 Bert Mackay (880 yards), Alex Brown (Mile), and Ian McCafferty (Three Miles) teamed up with Andy Brown to win the Mile medley relay while A Robertson won both sprints. For Kirkcaldy, there were three wins in the Junior age group – D Henry won the Mile, A McCulloch won the long jump and the club won the relay and in the Boys age group, D Wann won the 100 yards. One of the club’s younger athletes was credited with a 100 yards time of 10.1 when Junior (ie Under 20) Ian Donaldson of Kirkcaldy HS and Kirkcaldy YMCA ran it in Anstruther in June.

In the 1967 championships, held at Grangemouth the Motherwell juggernaut was back in action with the Brown brothers, McCafferty and McKay leading a good senior team but the Kirkcaldy men were more noticeable than in previous years. D Neilson was second in both 100 and 220 yards, J Hutt was second in the long jump and the Kirkcaldy senior men’s team won the medley relay. They also won the Youths 4 x 200 yards relay and A Robertson won the 100 yards in 10.6. A third relay success came in the Boys age group when they won the 4 x 110 yards relay as well as A Mitchell winning the long jump. There was also a club points plaque competition for all age groups and Kirkcaldy won the trophies for the Youths (ie U17) and Boys (U15) age groups. It had been a really good day for the club with the range of success spreading over all age groups and across all events. These events show a developing club but there was not the same degree of success at the East District championships which were a step up. However in May 1968 the Boys from Kirkcaldy showed the seniors the way: S Robertson won the Youths 100 and 220 yards events in 10,2 and 23.4 seconds – remarkably good times for an Under 17 athlete – and G Ferguson won the shot putt with a 41′ 2″ putt. There was no follow up in terms of titles won at District level after that year but the club was represented at the East Championships.

In addition to the YMCA and East District Championships, there were numerous inter-club fixtures with other clubs such as Pitreavie AAC, Larbert YM, Forth Valley AC and Tillicoultry as well as some of the Edinburgh clubs. There were also several appearances in the Scottish ranking lists. Ian Donaldson was credited with a ‘doubtful’ 100 yards time of 10.1 when a Junior (ie Under 20) in Anstruther in June, 1966, and was ranked fifth in the 200 yards hurdles for his time of 24.6 run at the same meeting – he was also third in the Scottish Schools hurdles event iwth a time of 24.6. In 1968, Alex W Robertson was ranked number two Youth in the country with his best 100 yards time of 10.2, and for the same event won the East District Championship (10.2), the Scottish Schools (10.8) and the SAAA (10.6); he was also second in the 220 yards list with 22.9, run at Grangemouth on 22nd June and he won the East, (23.4) the Schools (23.4) and the SAAA championships.22.9). The Scottish athletics handbook of 1969 called the latter “his victorious sweep of the titles”, and the only Youth to have run faster was David Jenkins. In the same year, R Sharp was eleventh in the 880 yards lists with a best of 2:03.3 run at the SSAA championship. Robertson was also seventh in the 110 hurdles event with 14.8. It was a good year for the Kirkcaldy Under 17’s – G Ferguson was ninth in the shot putt with 41′ 2″ and Peter Blyth was third in the Javelin rankings with 156′ 7″ – he had also been third in the SSAA with 147′ 8″. Up among the Juniors, all Robertson’s marks saw him listed but added to them, David Smart was sixth in the 880 yards with 1:57.9 – he had also been second in the Schools championship in 1:59.4. Metric distances were starting to appear and Robertson was also credited with an 11.5 second 100m at Grangemouth on 21st September which placed him eighth among the Scottish senior sprinters. In 1969 Robertson was a Junior and was ranked 11th for 100m (11.5) – he was third in the schools with 11.8), seventh for 200m with 22.9 sec (second in East District with the same time) and second in the 110m hurdles with 15.0 sec (having won the East in 15.0 and been second in the SAAA 15.2). Robertson was a product of Buckhaven High School which was producing many very good athletes in the technical events and they even had a highy ranked decathlete in Ronald Thomson. Alex Latto had been ranked the previous year as a pupil at Kirkcaldy High School but in ’69 he was a member of the YMCA and topped the Youths shot putt with 46′ 10 1/2″, also winning the Schools (14’28) and the SAAA (13.95).

The new East District League had ist frist meeting in Dundee in April. 1968 and the new clubs added to those competing were Kirkcaldy YMCA, Forth Valley, Dundee Hawkhill, City of Perth and Tayside AAC. In the first match Kirkcaldy was third with 103 points behind Aberdeen and City of Perth. The league included girls events too. The club was clearly looking forward.

The club was undoubtedly doing well and recruiting from all the local schools – Kirkcaldy High School, Buckhaven HS, Glenrothes HS were only three of them. With this talent at their disposal in the younger age groups, and particularly the U17 and U20 brackets, their future should have been assured. They were winning cross-country titles in winter, on the track they had some outstanding young athletes across the board from sprints to middle distance and in ths throws and jumps.

But the club seemed to disappear in 1970. Having searched in vain through all the newspaper archives to which I had acess, I asked a long standing official, coach and administrator from Fife what had happened to the club. Like me, he could find nothing after December 1970 when Kirkcaldy organised their last East District League race. He thinks it may have been that a key figure in the administration and official roles left then, and adds, “After that Clubs like Glenrothes, Cupar & Fife Southern (Kirkcaldy based) appeared and eventually amalgamated to become Fife AC who have organised the odd East District Cross-Country League in the recent years.”

I asked an experienced competitor and official about how the success for the younger athletes for a whole decade came to pass and also asked whether there was any significant driving personality behind it. His response: “However it happened and why it happened is still a bit of a mystery but it was a loss to the sport. The club had played its part in the sport, contributing at least its share of the work necessary – for instance it was an annual venue for one of the yearly three East District Cross-Country League races, from 1925 till 1954. Other venues were asking to host races, and the next one at Kirkcaldy after ’54 was in November 1963. They supplied officials for local meetings and for championships. One of the best known of these was Jimmy Cooper who was a full time Youth Development officer with them – he was very keen on Cross-Country so might have been a driving force behind them at that time. “

It is however still a bit of a puzzle how a club whose young athletes were doing so well could just cease to exist as Kirkcaldy YMCA Harriers seemed to do.

I’d like to thank Alex Jackson, Graham McDonald and Ken Mortimer for their help in doing the profile.