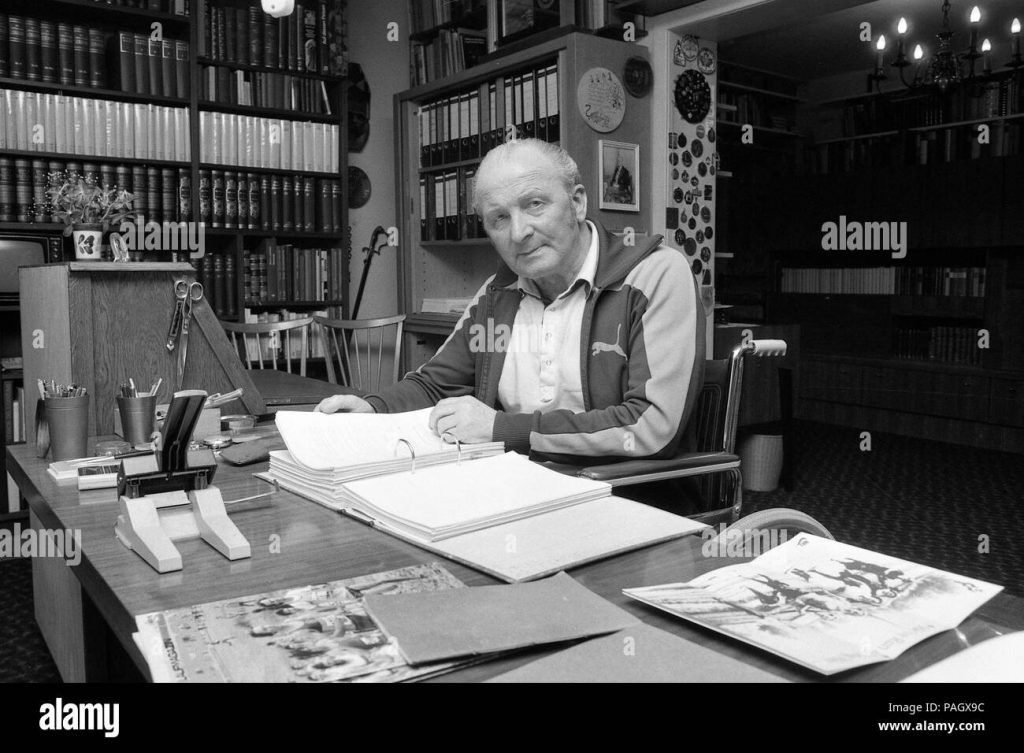

Van Aaken on the right.

Arthur Lydiard was the man who asked his athletes to run 100 miles a week for 10 weeks as part of their periodised training. They all did it His own athletes included such as Peter Snell (800m/1500m), Murray Halberg (1500m/3000m/5000m) Barry Magee (marathon). When his book ‘Run to the Top’ came out in 1962, many seized on the magic 100 mpw (round numbers attract, his runners were successful) and put it into their programme. Scotland was no different to the rest of the world – if it worked in New Zealand, Finland, Mexico and over countries where Lydiard worked and coached, it would work here. Scots could be seen running along the road, over the country and up and down hills in their effort to reach the magic number. The question in 1960s and 70s Scotland was not “Do you run 100 mpw”, but rather, “Do you run them fast or slow?” Many found they could not manage to do that and race effectively but for a very high percentage of endurance men, it was a ‘must have.’

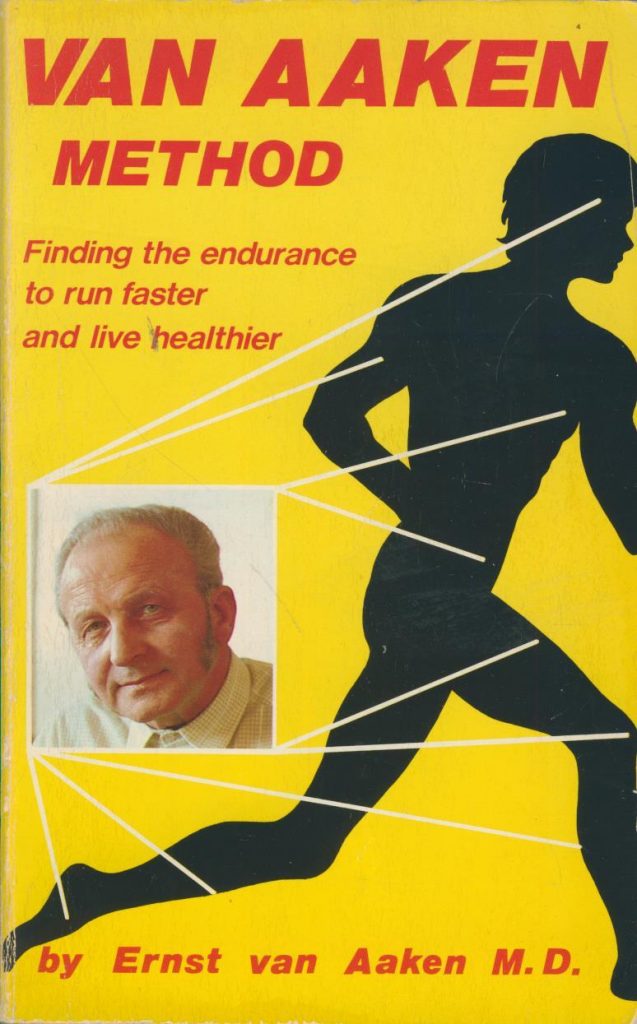

Then along came Germany’s Ernst van Aaken and long slow distance running. LSD was the abbreviation for the training system. Unlike Lydiard, the pace was defined – slow; and also unlike Lydiard the distance was undefined – long as opposed to 100 mpw.

Ernst van Aaken (16 May 1910– 2 April 1984) was a German sports doctor and coach. Over time he was dubbed the Running Doctor and was responsible for the training method called the Waldnieler Dauerlauf (German: “Waldniel endurance run”). Several other coaches claim the honour but, insofar as it can be attributed to any one person, van Aaken is believed to be the founder of the long slow distance method of endurance training.

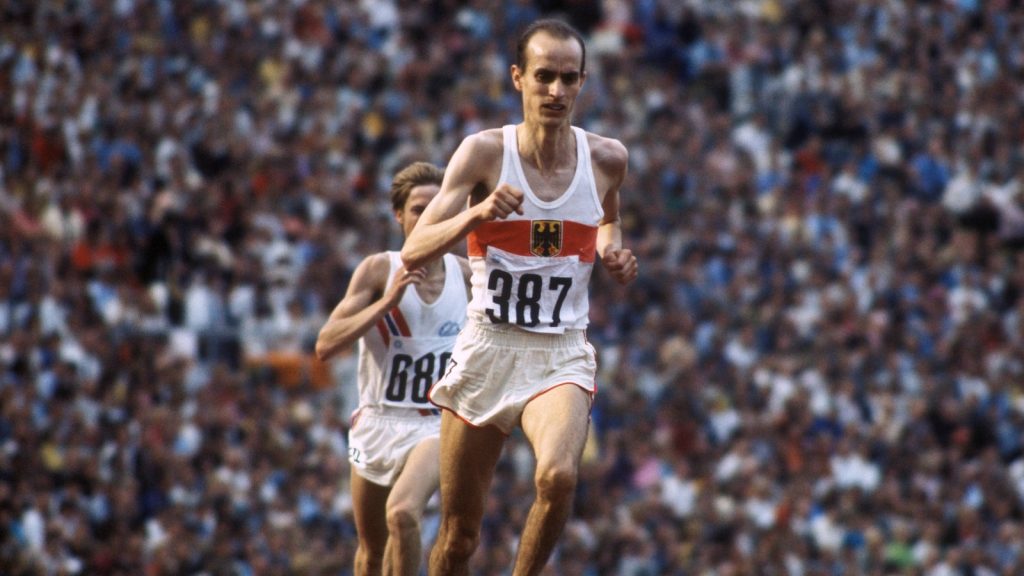

Once he had settled on this way of training, which he called ‘Pure Endurance’ , he was fanatical in his propagation of the method. He advocated it at the expense of interval training which had been the prevailing heresy in the 50’s and early 60’s. One of his athletes, Harald Norpoth won the silver medal for the 5000m in the 1964 Tokyo Olympics.

Norpoth really was a class runner – in the European Championships in 1966,, he won bronze in the 1500m and silver in the 5000m, and set a 2000m world record of 4:57.8 in September 1966. He had a relatively long career with third place in the European Championships 5000m in 1971 finishing only 1.2 seconds behind the winner. Almost skeletal in appearance, he was 6’0″ tall and weighed in at less than 10 stone. He was able to follow a fast pace and also had a feared finishing kick.

The tale is told of a young Ian Stewart being defeated by Harald Norpoth after a really hard battle after which they were both totally drained; Lying on the ground Ian saw a TV cameraman passing and called him across. Looking into the camera he is quoted as saying something like “That was bloody hard Harald and you won this time, but I’m telling you now, you can expect more of the same every time you come up against me!”

Harald was coached by van Aaken and was the most famous of his athletes. Although van Aaken had formed his theories and been practising them himself as well as being a strong advocate for them since 1947, it was the 1960s before they became common currency. The following extract comes from the Science of Running website and can be read in its entirety at

Ernst Van Aaken: The Pure Endurance Method – Science of Running

“His method consisted mostly of slow running, with Norpoth’s training consisting of 90% of his runs at between the heart rates of 120 and 150. Even during his harder tempo run, his heart rate only reached around 180, still well below his max. Van Aaken believed that the key to running was to get oxygen into the body and increase the size of the heart. To accomplish this he recommended running long distances at slow paces, thus lower heart rates (about 130bpm) and to only rarely accumulate any oxygen debt. At the time, this was revolutionary thinking because he directly contradicted the prevailing wisdom: the famous German interval method designed by Woldemar Gerschler that said you run a repetition raising your heart rate to 180 and then recover until it reaches 120, when you start another repetition (and so on).

Van Aaken’s model depends, instead, on long runs with a heart rate of 130 and short bouts at race pace over a small portion of the desired racing distance. An example of the short sessions might be 3x500m at mile pace with plenty of recovery (~ 5 minutes) after an easy run. If you’re training for the 5k, then an example would be 2-3x1000m at 5k pace with several minutes recovery. One example given for a 15 minute 5k runner to do 12x 400 in 72 seconds with a full recovery of 200 meters of walking or 400 meters of slow jogging.

In addition to his “pure endurance” method, Van Aaken had some unique ideas on what would change in the future in training. In his book, he gives an example for a runner who wants to run 3:20 for 1,500 and 12:45 for 5,000m. Dr. Van Aaken believes that the training might include up to 40 kilometers a day spread out over up to 5 runs per day. In addition, he believed the limiting factor in distance running was getting enough oxygen to your cells, thus aerobic development was key.”

What did we take from it? 5 runs a day was one thing which to any working man – and we were all working men or women (for van Aaken was a proponent of distance running for women) – would have found almost impossible.

After reading his book, it was seen that there was much more to him than that. From the same article as that quoted above, we get:

Van Aaken’s views on Speed and Mileage:

In Van Aaken’s book he has a chapter entitled How much? How Fast? to answer these questions. It starts with a generic chart for mileage per day based on event:

• Race—Training done per day

• 400 meters— 6 kilometers

• 800 meters— 10 kilometers

• 1500 meters— 15 kilometers

• 3000 meters— 20 kilometers

• 5000 meters— 25 kilometers

• 10,000 meters— 30 kilometers

• Marathon— 40 kilometers

In addition to the slow mileage and tempo runs, Van Aaken included some pure speed or sprint work. He advised doing sprints of 50 meters. These sprints were to be done as sharpeners only occasionaly. The reason these were done is because they were so short, that no oxygen debt occured. One of Van Aaken’s key principles is to not run in oxygen debt during training as this is not what the body was designed to do.”

He was a coach whose ideas were never seriously adopted by Scottish or British marathon runners. He never laid out his yearplan as other more fashionable coaches did – Lydiard had his periodisation plan neatly laid out and British coaches had their own ideas nicely set out in Athletics Weekly or BAAB coaching booklets – and there was an almost wilful misunderstanding which boiled down to an almost scornful “Who can do 4 hours running a day? “Where can I get in 5 runs a day?” Nor, to the best of my knowledge were these ideas discussed or mentioned at SAAA coaching courses. Here then we set out his rules for running as set out by the man himself (note the comments on weight).

Van Aaken’s key rules for running:

(As found on page 56 of The Van Aaken Method)

• “Run daily, run slowly, with creative walking breaks”

• “Run many miles, many times your racing distance if you are a track runner; up to and often beyond if you are a long distance runner. Do tempo running only at fractions of your racing distance.”

• “Run no faster during tempo runs than you would in a race.”

• “Bring your weight down 10-20% under the so-called norm and live athletically- i.e., don’t smoke, drink little or no alcohol, and eat moderately.”

• “Consider that breathing is more important than eating, and that continuous breathlessness in training exhausts you and destroys your reserves.”

Diet and sleep

A central theme of Van Aaken’s method is that the athlete should have very little fat on his body. The lighter the athlete the better. He took this to the extreme with his athletes stating that the runner should eat very little, about 2,000 calories per day. Which is not very much at all considering the vast amounts of mileage his athletes did. He wasn’t strict on what the athlete ate exactly, as long as he did not eat too much. It was recommended to eat a good amount of high quality protein and to limit your fat intake to less than 40 grams a day. In addition, he believed that a runner should fast for a day occasionally. Van Aaken said that the fasting taught the runner how to run with little fuel supplies and to teach his body how to burn fat.

In addition to his different views on diet, Van Aaken also had controversial views on sleep. He believed that contrary to what most believe, that people sleep too much. He would often limit his own sleep to only a few hours.

The web link above is very interesting to anyone involved in long distance running and who wants to know more about the methods advocated by Van Aaken including six takeaways from his training for today’s athlete.

In 1972 Van Aaken was hit by a car while out running and lost both legs. Confined to a wheelchair, he became also a champion for disabled sport and wheelchair racing. Other countries showed more interest in the man and his ideas and theories than we did and he held countless lectures mainly in the United States and Japan. He also organized running races, especially marathons for women, besides ultra distance running events.

In the 1960s, and maybe more often in the 1970s we did talk about him but maybe not as much as we should have done – although his book ran into several re-prints.