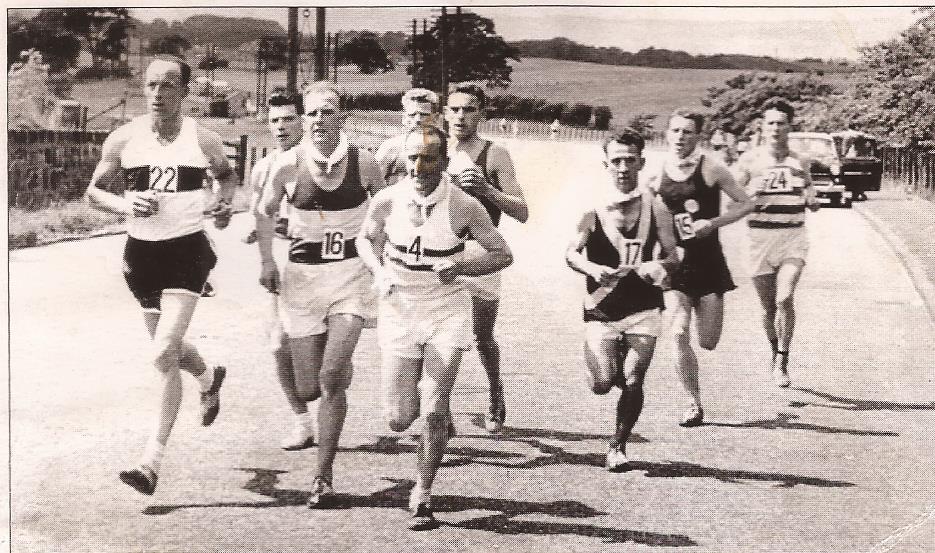

Harry is Number 17 in the Picture taken during the 1957 SAAA Marathon which he won.

(Also in the photo are George King, Emmett Farrell, Andy Fleming, Hugo Fox (head only), Andy Brown and Ronnie Kane.

I first met Harry when I was about to run my first Edinburgh to Glasgow Relay race. I got on to the bus for the third stage and was hardly into my seat when a wee man got in and sat beside me. We didn’t know each other and had never met but he started in right away saying he was delighted to be running the third stage for the first time ever – it meant he’d be able to visit the Forestfield Inn for the first time in ages at the end of the fifth stage! His patter was terrific and his manner infectious: I lost a lot of the nerves and was feeling quite positive and positively cheery when we got off the bus to start warming up. We met frequently after that for almost 50 years and at one point when his son was training with our group at Crown Point, we took turn about buying the tea and fudge doughnuts when the guys were out for their jog after the session.

Harry was one of the most popular men in Scottish endurance running in the 50’s and 60’s and even after he retired he went to all the races to see his son, young Harry, race and was always in among the chat with the runners, with the officials and with the supporters regardless of their age or club affiliation. My first meeting with him was at the start of the 1958 Edinburgh to Glasgow Relay. I got on the bus for the third leg and immediately afterwards Harry plonked himself on the seat next to me and started chatting away. Apparently he had been asking for that stage for ages so that he could run, get dressed and be ready for the Forestfield Inn at the start of the long sixth stage. Everyone remarked on his height because he was so small – he could certainly give Dunky Wright a run for his money in the wee-ness stakes! But given his size and the size of his heart he must have had a huge power : weight ratio.

After the was Clydesdale Harriers organised one of the first annual races for the Under 17 (Youths) age group in the form of the Youth Ballot Team Race with the winner being awarded the Johnny Morgan Trophy. It was a Ballot Team race because not all clubs at that time had many runners in what was at the time the youngest championship age group. It was won by man top class young athletes such as Ian McCafferty, Lachie Stewart and John Lineker. Harry won the race in his first year in the Youths age group and went on to win many races in all age groups thereafter. His first Senior title was in 1954 when he won the Midland District Cross Country title at Woodilee Hospital in Lenzie and then he ran well enough in the National Championship to be selected to run for Scotland in the International fixture in Birmingham. His next international honour on the country was in 1957 after he won the cross country championship at Hamilton Racecourse. The win was reported in Colin Shields’s book “Whatever the Weather” as follows:

“Harry Fenion, nine years after winning the National Youths title, scored a surprise victory in the Senior nine mile race. With no one willing to take the lead there was a close group all together at six miles until Fenion broke clear and opened a gap. Bannon, the holder, dropped back just when he previously proved to be his strongest leaving Fenion to win by sixty yards.” He then ran in the International where he had a bad fall at an obstacle in the first lap meant he could not compete properly. He finished fifty first – twenty seven places further back than in 1954. In 1958 he again made the team and finished forty second – in all three he was a counting runner for the Scottish team. Clyne and Youngson’s version of the same race is this “The sensation of the 1957 National CrossCcountry championship was the victory of Harry Fenion of Bellahouston Harriers. Harry, Youth Champion in 1948 finds himself nine years later the Senior king-pin. Everything went right for him and when at six miles he elected to go away no one could hold him. His pace uphill and downhill was devastating and completely demoralised the field. Small but neatly and compactly built his running on this occasion reminded Emmett Farrell of an old poem remembered from school days:

“Up the airy mountain

Down the rushy glen

We daren’t go a-hunting

For fear of little men.”

His marathon running started in 1956 when in John Emmett Farrell’s words “A strong rival for Joe McGhee had announced his excellent form on the roads. Harry Fenion of Bellahouston with his ‘very easy, choppy stride’ broke the course record for the Clydebank – Helensburgh 16 beating George King by one and a half minutes.” In the SAAA Marathon Championship that year he kept up with Joe McGhee (winning his third consecutive title) as far as twenty three miles before having to withdraw due to ‘blisters and inexperience.’ In 1957 he was known to be keen to add the marathon title to his cross country performance. he again won the Clydebank – Helensburgh 16, narrowly beating Andy Brown of Motherwell. There was some doubt about Joe McGhee and Harry became favourite for the SAAA Marathon Championship. Back to Clyne and Youngson –

“The 1957 race took place on the22nd of June finishing again at Meadowbank and Harry did indeed achieve his ambition and become the only man to win the National Cross Country and SAAA Marathon in a single year. The training Harry did was rigorous. ‘I usually averaged 130 miles a week which included running three times a day, gradually adapting myself to running 5:30 a mile which was race pace. This was done with the help of my friend who came along on his bike. He used to time each mile which was good because I was able to increase the pace and come back again to a steady 5:30 pace. The longest run I ever did was 33 miles. I usually did 20 miles which included fartlek sessions. All this training was done in the morning at 7:00 am before starting work and then again at lunch times and again in the evening. During training sessions I never ever drank any fluids. My diet included at least three steaks a week one of which was eaten about two hours before a race. I usually wore black sand shoes from Woolworths and put a Boots the Chemist’s insole in them. They did not last very long as the roads where I trained were very rough.

The weather for the race was cold, mainly dry, and at times wet – ideal conditions. For the first ten miles I sat in the pack watching everybody. Shortly afterwards I kept asking when the next drink station was making out that I was desperate to take water on board which I wasn’t. This was part of my race tactics. When we approached the watering station the other runners moved across to get a drink expecting me to do the same, but to their surprise I never took any and put in a kick that left the pack. Most of the runners dropped their water to chase after me. I met my coach shortly after the break and said “Next stop Edinburgh!” As I was out on my own I started to run at my own pace and pull further and further away. At 23 miles I took a stitch after stepping down from a particularly high pavement and had to ease down for a bit. It wasn’t until I entered the track that someone told me I had a chance of beating the record. I took one final spurt and just managed to beat it. If I had known earlier I would have taken more off the time.’ Harry’s 2:25:44 broke Joe McGhee’s championship record by six seconds. Hugo Fox was second in 2:28:57 and George King third in 2:37:20. ‘After the race I ate a couple of oranges, had a shower and then went for a three course meal. My time was the fastest in Britain and the second fastest in the world that year’.

Jackie Foster remembers Harry as being under 4’10” in height but making up for this in speed. ‘His wee legs seemed like Mickey Mouse toys where the feet are fixed to a fairly big wheel that spins as the child pushes it away from himself. In one race I was in fourth place about a hundred yards down on Harry and two others (Fox and Kerr) as they approached the large floral roundabout at Maybury. Harry made the break and ran straight across through rose bushes, flowers the lot. The other pair anxious to keep up with him did likewise. The policeman on duty tried to call them back but they were away. he did however make me and the others follow the correct route. I once asked Harry how it felt to run as fast as he did in the hope there was some secret he would reveal. He replied that it was “Sheer hell!” So that was how he managed to do it – pain tolerance.'”