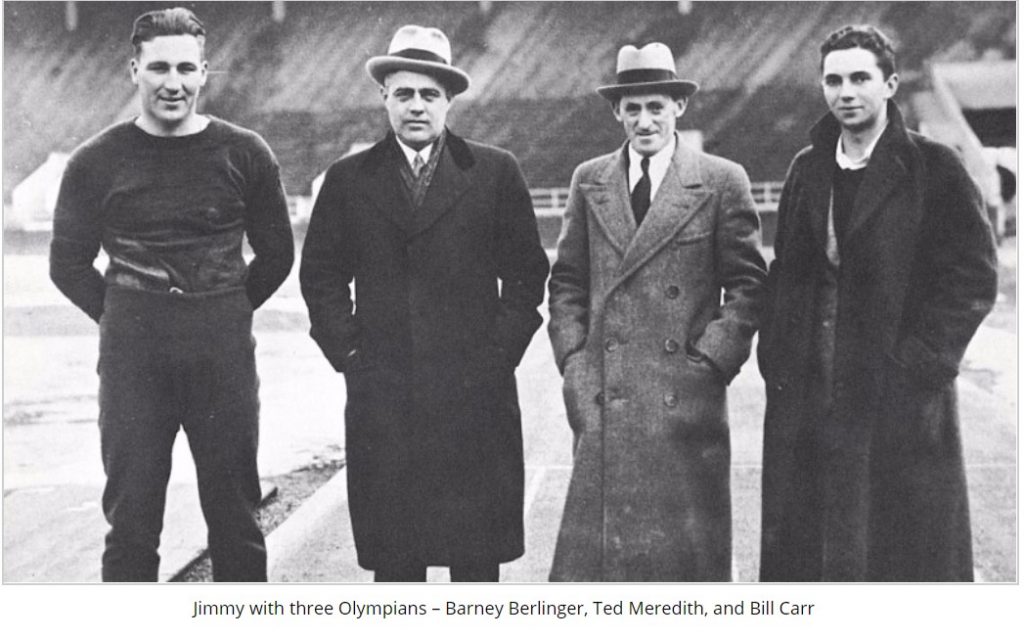

James Curran was an athlete from the Scottish Borders who emigrated from Galashiels in 1910 and only two years later trained the 1912 Olympic 800 metres in Stockholm, Ted Meredith. Meredith not only won but broke the world record in the Stockholm Olympic final. Curran went on to become a legendary coach in the US, training several Olympians over 50 years. Curran is acknowledged as one of the top track and field coaches in US athletics history.

*

Originally Jimmy Curran had been a member of Gala Harriers – indeed he was captain of the club – and ran well in half-mile and mile races. Living in the Borders where there was always a thriving pro scene, he knew he was good enough to make some money as a professional and left the amateur ranks in 1905 to run in the Hawick Common Riding Sports. Like many professionals did, even well into the twentieth century, he ran under a pseudonym – in his case ‘G Gordon’. He did well and at New Year, 1907 running in the half-mile at the Royal Gymnasium Grounds he won from a mark of 15 yards and returned in the three following years. In 1907 he went to America for a short spell but came back to race in Britain again. He also won the Powderhall 300 metres Sprint in 1910 before emigrating permanently to the United States later that year at the age of 30 to become coach at Mercersburg University.

His biggest contribution to Scottish athletics, however, was probably through his work with Wyndham Halswell. William Reid was an athletics journalist under the title of Diogenes at the start of the 20th century, and in “Fifty Years of Athletics” (1933) commented that “A short while ago I got a letter from Jimmy Curran, a Galashiels man, who has for almost a quarter of a century been one of the most distinguished athletic coaches in American school and college athletics. He went on to say that Curran found Halswell and gave an outline of the relationship. As we will note later, Curran was a great letter writer.

Wyndham Halswell

Curran had been in South Africa with the Highland Light Infantry during the Boer War (1899 -1902) where he met Lieutenant Wyndham Halswell. On his return he induced the young lieutenant to start training seriously and is generally recognised as the first man to recognise the outstanding talent. They were a real contrast, an unlikely pairing – the tough, uncompromising professional who had fought through the War, and an officer and a gentleman. There is a lot of good information on the duo, and on Curran’s philosophy generally, in John Bryant’s excellent book ‘The Marathon Makers’ from which the following comments are taken:

Given Curran’s approach to both the practicalities and the theories of human performance, it is little wonder that he wanted to apply his knowledge and experience to the gifted Halswell, but this team of amateur and professional was bound to lead to tensions.

‘It’s no use learning to run like a deer if you let others make you a target, and cut you down with cunning,’ Curran would warn. ‘There is no justice in sport,’ he would growl,’ ‘If you think you will win because you were better, or because you did everything right, or that you will lose because the other man deserves it, then you are a loser. You win by outwitting your opponent with luck, or because of his mistakes. If they give you half a chance to win, then beat ‘em.’

With his experience as a professional, Curran could explore that fine line between out-and-out cheating and being cagey. In some cases, he realised these were part of the game, even a big part – sharpening the buckle of a belt and using it to scuff a cricket ball, or keeping your mouth sht when the referee fails to notice that you have beaten the starter’s gun. ‘These things go on,’ Curran would say, ‘Sometimes if you want to win, and you think you can put one past them, then you’ve got to try.’

Halswell would hear those views and he didn’t always agree with them or the philosophy they carried, but one thing he was sure of was that his visits to the track could teach him much. Curran taught him the secrets of the punchball for speed, of distance work for stride length and dumb bells for strength.

‘Keep your body fresh,’ he would advise, sharing that nineteenth century preoccupation with how the human body might react to being pushed to the extreme.

*

Curran realised that once Halswell got in front in a race he was unbeatable but he still had to learn to fight in a tight corner.

‘Your job is to win, right?’ So concentrate and do what’s necessary now. If you are thinking, I failed in the past, and I’m going to get beaten now, then go home and don’t bother to compete. I’m not saying it’s bad to lose, but it is bad to give up when you’ve still got a chance. ‘

‘Courage,’ Curran would tell him, ‘is a form of stubbornness. It’s a refusal to quit when you want to quit because you are tired or broken. You need it in everyday life and often everyday courage is more important than the great deeds sort of courage.’

We well know how successful Halswell was, and the philosophies expounded by Curran went with him to Mercersburg. It was a comparatively new college, founded in 1893, and one of the coaches before him had been a hard act to follow: Alvin Kraenzlein had won four Olympic golds at the 1900 Olympics and was known as the ‘father of modern hurdling’ and as a pioneer of the straight lead leg in hurdling. But Curran he threw himself into the sport in America straight away and was thrilled by the standard of athlete he encountered. In Olympic year he wrote letters home to several newspapers (The Daily Telegraph was one of the first and the Glasgow Herald was also on his list) about the talent that abounded there. In May, 1912,the following note appeared in the ‘Sports Miscellany’ column of the Glasgow Herald:

“An old Scottish runner in an interesting communication on American athletes to an English paper, supplies the following particulars of the running of John Paul Jones who would seem to be the ‘last word’ in distance racing:

“You have no doubt heard of John Paul Jones of Cornell. He is all he is cracked up to be and a little bit more. I have seen him run only once and that was when he beat Billy Paul a grand little runner who did 4:1 4-5th making all the running himself and who should have gone faster the next year if everything had broken right for him. In the last mile of the four mile relay in Philadelphia last April, Jones was clocked in 4:22 and had a lot in hand. He ran in the mile two weeks later in 4:12 4-5th beating Paul out on the home stretch by five yards on the same track. Then he finished up by winning the Inter-Collegiate mile in 4:15 2-5th. College runners say he could have run 4:12 if pushed. I should like to have seen Tincler at his best against him. I do not say he would have beaten George but he certainly would have given him a great race. I hope he visits England after the Olympiad, then Englishmen will see some of the best distance running they have ever seen – if the climate agrees with him. There are several more who can get inside 4:20; I should say about four or five.”

The old Scots runner was clearly Curran and this appeared in the Glasgow Herald on 10th June that year, just before the Stockholm Olympics, he wrote to the ‘Glasgow Herald’.

“America’s chances at Stockholm look brighter than ever. Some wonderful performances have been recorded in dual meets these last two weeks, though this is the worst Spring I have ever seen for getting a team in shape. Mike Murphy says he has been in the game for 30 years and a worse spring he has never encountered. Look out for records this year when the boys get into condition. America will send over the greatest team this year that has ever been gathered together. It will take 12 feet 6 inches to win a berth in a team of pole vaulters, and about 6 feet 3 inches for the high jumpers. I saw Mercer of Pennsylvania, do 23 feet 6 inches broad jumping last Saturday, and he is not the best long jumper in America by a long shot. If the track at Pennsylvania Relays had been in good condition, I feel that Gutterson of Vermont University would have done close on 25 feet. He did 24 in mud. I should not be surprised to see four men do 24 feet. No wonderful time has been done in the sprints as yet, but that is owing, I think, to the cold weather. In the 440 and 880 some great running will be done. All the 440 men who leave here will do 49 sec and the half-milers will make Melvin Sheppard run his best. My boy Meredith will do 1:54 or better and at least 48 3-5th sec for the quarter. This is for the full distance – 440 and 880 yards – and when you consider the Olympic distances the times will be correspondingly lower. The milers will all do 4 min 20 and Barns of Cornell, who ran the two miles in 9 min 17 sec two weeks ago, will need some watching in the longer distances.”

Sounds almost too good to be true and the Herald commentator was moved to say “All this reads like a romance, and if Curran’s predictions are fulfilled, Britain would seem to have small chance of success in any of the pedestrian events at Stockholm. But much the same tale was told at the time of the last Olympics at London, and it may be remembered that the Union Jack was hoisted at some events over which the Stars and Stripes were expected to wave merrily. And history often has the knack of repeating itself.”

Whether Curran’s optimism was justified or not can be seen from the fact that USA won gold in 100m, 200m, 400m, 800m, hurdles, 4 x 400m, 3000m team race, long jump and pole vault; silver in 100m, 200m, 800m, 1500m, 10000m, sprint hurdles, long jump, high jump, shot, discus and two in the pole vault; bronze in 100m, 400m, 800m, 1500m, hurdles, high jump, long jump, pole vault, shot, discus and hammer.

In particular the success of his 800m runner, ‘ my boy’ Ted Meredith, in winning gold and setting an Olympic record of 1:52.8 must have fired him up even further. Meredith had come to Mercersburg as a good quality runner but Curran sharpened him up considerably. Some of the run-up to the Olympics was described in the Mainline Today:

In April 1912, Meredith was back at the Penn Relays as anchor of the Mercersburg team, which won its event by 50 yards. Two weeks later, he set world interscholastic records in the quarter- and half-mile, covering the latter in 1:55. “Meredith doesn’t seem to know how fast he can run,” Curran said. “But I know he’s the fastest runner the world has ever seen.”

Curran thought the Olympic trials at Harvard University would be a good experience for Meredith. He made the team after winning the first 800-yard heat in 1:53 4/5—the same time run by Mel Sheppard in a subsequent heat. Sheppard, of Deptford County, N.J., had been the top U.S. runner at the 1908 Olympics, where he won four gold medals.

Curran later claimed that, in the trials, he deliberately put Meredith in the 880 rather than the 440—which, with weaker competitors, he could have run “in a walk.”

“I told him to run his own race in the final,” wrote Curran in Recreation magazine, “as he would be sure of the team now, and see if he could beat Sheppard in the sprint, a thing no runner had been capable of doing when Sheppard was fit.”

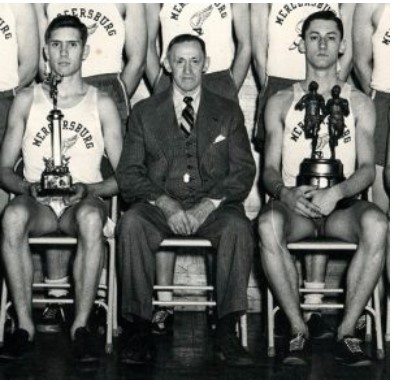

From the time he arrived he started making changes. For instance the Williams Trophy was awarded for a pentathlon competition – 110m hurdles, 400m, 1600m, long jump and shot putt – but Curran changed it so that it was a selection process for his team. There was no doubt that the successful college team was Curran’s team. The USA college athletics scene is a hectic one with athletes competing wherever, whenever the college requires them to and Curran was at the heart of it. The detailed programme for the 80th Annual Eastern States Track and Field Invitational programme says in its introduction:

“It was in 1934 that the Amateur Athletic Union first held an interscholastic meet at the old Madison Square Garden on 50th Street and 8th Avenue. There had been a “national”championship held earlier at the Newark Armory under the auspices of the St. Benedict’s Prep, a charter member of the New Jersey Catholic Track Conference, but it is from the Garden meet that the meet you’re attending today – The Easterns – draws its lineage. The meet remained at the Garden until 1965, when the AAU decided to take its championships on the road for a couple of years. The 1934 meet had just one division, won by Jimmy Curran’s team at Mercersburg Academy, located in remote, rural Central Pennsylvania, about 75 miles southwest of Harrisburg. It was under Curran’s tutelage that several world-class athletes developed at Mercersburg, including 800-meter run world record holder Ted Meredith.”

Note the ‘located in remote, rural Central Pennsylvania’ bit: it is still not uncommon for a coach to lament that there are no good athletes in a particular area, and yet coach Arthur Lydiard produced a squad of world beaters whereever he went from New Zealand, via Europe to Mexico. There are many examples of coaches who continuously produce good class athletes from small areas. Nearer home there are coaches who move around the country and have almost all-star squads in every location. Curran went on in remote Pennsylvania for half a century delivering the goods.

He was to be at Mercersburg for 51 years – ie until he died in 1961 at 81 years of age – and in all that time he coached or developed 13 Olympians including

* Ted Meredith, double Olympic gold (800m, 4 x 400m) in 1912 at Stockholm;

* Bill Carr, double Olympic gold (400m, 4 x 400m) in 1932 at Los Angeles whose career was cut short by a car accident in 1933;

* Charles Moore, double Olympic gold, (400m hurdles, 4 x 400m relay), 1952 Helsinki;

* Alan Woodring, Olympic gold (200) in 1920 at Antwerp.

An article in the Mercersburg yearbook 0n 20th December, 2010, under the heading “Olympic Medals Find A Home At Mercersburg’ quotes Charles Moore and it reads as follows:

“Olympic gold medallist and USA Track & Field Hall of Fame member Charles Moore has donated the gold and silver medals he won at the 1952 Summer Olympic Games to Mercersburg. The medals will be displayed in the school’s renovated Nolde Gymnasium. Moore won the 400m hurdles in the record setting time of 50.8 at the 1952 Summer Games in Helsinki and also ran the third leg of the mile relay for the silver medal winning USA team. He was an NCAA champion in the 220-yard low hurdle and 440 yard dash at Cornell University. He also won four straight AAU titles in 400-meter hurdles from 1949 to 1952. The US Olympic Committee named Moore as one of its 100 Golden Athletes in 1996.

“I owe everything in my Mercersburg career to Jimmy Curran, who simply turned to this kid who had never – ever – run and said, “Here, let me help you.” More says.”

An Article on Allen Woodring on the Family Search website says “For his education Woodring attended several prestigious academic institutions including Peddie Institute in Hightstown, NJ, then at local Bethlehem Park, and finally to Mercersburg Academy, graduating in the class of 1918. At Mercersburgh, under the tutelage of coach Jimmy Curran, he began to develop his championship potential as a sprinter on the track team.

Competing on the high school level, Woodring topped the state list in both the 220 and 100 yard dashes in his junior and senior years. Setting the state record 0f 21 3/5th seconds in the 220 yard dash as a senior in 1918, he was named first-team All-American. Also in his senior year, Woodring was the National inter-scholastic champion in the 70-yard dash. Undefeated as a senior in major inter-scholastic meets in both the 70-yard and 100-yard dashes, he led both national lists for the year, and also led the nation in the 100 during his junior year.”

As for Carr,

“1932 Olympics, USA Track & Field: Bill Carr was the second Mercersburg track athlete to win two gold medals in an Olympics, racing to the top of the podium in one of the most noted 400 meter races in Olympic history and anchoring the triumphant 4 x 400 meter relay team at the 1932 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles, California. … Carr, a member of the US Track Hall of Fame, was never beaten in a one-lap distance.”

The track at the college is still, in the twenty first century, called the Jimmy Curran Track and his name still appears college publications, indicative of the fact that he is still highly regarded there, 50 years after his death. I quote from two fairly recent references to him. On 4th April 2016 – note the year – in an article in the “On Track” series in the college publications, there is an interview with coach Nikki Walker who is the current head coach for both girls and boys outdoor track and field teams.

“Question: But isn’t track also an opening for a kid who really may not have excelled at any other team sport but discovers that he or she can really run? Walker’s response: Yes, and that was the sole philosophy of our storied track coach, Jimmy Curran: if you come out for track, I’ll make you better. CharlieMoore ’47 is a perfect example of a kid who had no background and went on to become an OIlympic gold medallist, and it all started out for him right here at Mercersburg under Jimmy Curran.”

Back a bit, in August 2008, the Track and Field News had a poll to find the five greatest USATF Coaches of all-time and among the nominations was Jimmy Curran. He was right there with Tom Tellez, Bill Bowerman, Jumbo Elliott, Brutus Hamilton, Payton Jordan, Mike Murphy and the top men of all time.

Nor has he been forgotten back in Scotland: Curran was inducted into the Scottish Borders Sporting Hall of Fame in 2008. In addition, the European Coaches Association is considering awarding Curran a place in its own hall of fame in recognition of a lifetime of achievement in track and field coaching. Curran is possibly the Scottish Borders’ greatest ever Olympic coach and it is said that, despite achieving global success, in a career at Mercersburg Academy that lasted 51 years he never forgot his roots.