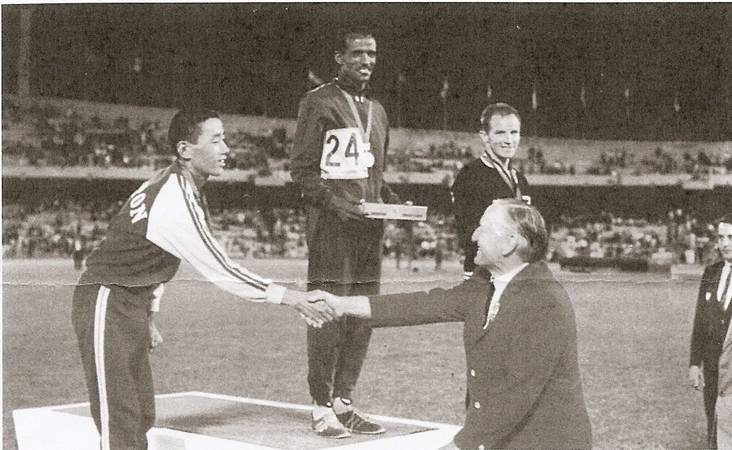

Kenji Kimihara receives his silver while Mamo Wolde and Mike Ryan look on

Mike Ryan was the only sea level athlete to win an endurance medal in the Mexico Olympics in 1968. Distinguished athletes such as Australia’s Derek Clayton and Ron Clarke failed and British runners like Ron Hill and Tim Johnston (who lived at altitude in Mexico for 18 months) performed below expectations. In fact Mike nearly didn’t make the Games at all and Peter Snell didn’t give him much chance before the event either.

I quote from ‘The Marathon Book’ by David Martin and Roger Gynn – “Wolde’s 2:20:26.4 was slower than Bikila’s times in Tokyo and in Rome otherwise it was the fastest marathon gold medal in Olympic Games history. Given the altitude it was a fantastic performance. After about three minutes Kimihara and Ryan entered and they finished 14 seconds apart. Behind them the sight of 54 more finishers entering singly – having just endured a hypoxic hell – was not pretty to watch. Tim Johnston and Akio Usami were within 1.8 seconds apart in placing 8th and 9th but neither could muster a finishing kick. …………………………………….. The final finisher of the day was Tanzania’s John Stephen Akhwari (3:20:46) later identified for special recognition as one who symbolises Olympic ideals. As he hobbled out of the approaching dusk onto the illuminated track his right leg bloodied and bandaged at both the knee and the thigh the estimated 10000 spectators began to clap for him in appreciation. By the time he finished the crowd had gone wild; one would have thought he had won. He did, in his own way. At the Press conference he was asked why he had not quit once he had realised he was in such a sorry state. His reply remains a classic: “My country did not send me here to start the race. They sent me to finish the race.” He went on to finish an excellent fifth place (2:15:05) in the 1970 Edinburgh Commonwealth Games marathon.” It was quite an occasion and a tremendous performance from the boy from Bannockburn.

In what follows, I’ll use the standard procedure and look at the pre-Games period, the Race itself and the post race toll that it took on him.

Mike had been running well but the system in New Zealand at the time divided athletes into A Class athletes and B Class. Mike was in B Class and had to provide his own funding. This could have come from the Waikato Centre (like the Scottish East or West District) or from local people. In fact he got funding from both and he was going to the Olympics. Knowing full well the difficulties that he would face in Mexico City he started training even harder and sought advice where he could get it. And given that Arthur Lydiard was the Mexican National Coach at the time he got advice from him via Barry Magee – third placer in the Rome Olympic Marathon in 1960. He had many meetings with Barry and the advice was first, to get all his speed work done BEFORE going to altitude and to get himself really race hardened BEFORE going to altitude. That really pleased him because it fitted in with what he already had in mind. The training was hard. Sessions like 30 x 400 with a 200 jog went in and went well. The forest trails around Tokoroa were important they were away from the traffic, away from prying eyes, had good underfoot surfaces and were generally an inspiring place to train. He would put on his full NZ gear, jog to the forest and run at maximum effort for as long as he could – usually 45 – 40 minutes. Like all Olympians he was totally focused on the Games. When he heard that Peter Snell had said in an interview that he might do well but it wasn’t very likely, well that inspired him even more.

He travelled to Mexico with the team and among his friends and training partners was Peter Welsh, a steeplechaser who had newly qualified as a doctor. Once there Mike found training difficult. He couldn’t keep up in training runs with the Australians and the English or even with Peter. Things started to get a bit better then on the Wednesday before the race when out on the last long training run before the marathon on the Sunday he stepped on a rock of lava and rolled over on his ankle which immediately swelled up. Peter was very concerned and some local people drove him in to the village – although not as strict as it became after Munich, security was still pretty good but they did let them in with the athlete. The medics in the village put his ankle into freezing cold water and every time he tried to get it out they just pushed it back in again. Then they massaged it. However X Rays showed that nothing was skeletally broken. Later that day he was able to walk slowly round the track for an hour, on the Friday he did an hour’s run and on Saturday 30 minutes. On race day he did a light run in the morning.

He travelled to the Stadium with his coach and they were led into a room which he says reminded him of a scene from the Crimean War – people (runners) lying on camp beds all round the room with coaches talking to them and almost all looking very anxious. His coach was not like that so they just stood and had their first look at the Africans whom they hadn’t seen till that point. They were led out to a fanfare into the Stadium and when the race started he was in the leading group with runners like Clayton, Johnston, Adcocks, Hill, Temu, Gammoudi, Ackay and all the top men. He actually felt good running through Mexico City which reminded him of Fukuoka. The field broke up a bit and he ran steadily until at halfway he heard Ron Clarke shouting for Clayton and he had 100 yards on him. Turning a bend with about six miles to go he saw Johnston, Temu and Roelants ready to drop out and took heart from that. He knew that the Ethiopian was ahead but didn’t know if it was Bikila or Wolde. He was closing on them as they approached the Stadium up a series of steps. He knew that Ackay of Turkey was getting closer and still felt concerned. Then he got stomach cramps for the first time ever – he did all the usual things – bent over, massaged the area and so on – and continued. (Incidentally at that point he could smell the overwhelming odour of tortilla and chilli and when he smells chilli, even today, it brings it all back!). As he turned into the tunnel he heard a roar and didn’t know who or what it was for – Fosbury or Wolde. He felt there was a change in atmospheric pressure on the track itself. He looked back for Ackay but he was nowhere to be seen. So it was attempt to hunt down Kimihara but that was not to be and he finished 100 yards or so down. A wonderful race. When I asked him how he felt at the end he said relieved, exhilarated and a sense of achievement. He had earlier said that he had taken inspiration and solace from all the people who had beaten him and whom he wanted to emulate – people like Lachie Stewart, Fergus Murray, John Lineker, Bert McKay and all the rest – and he mentioned them all again saying that they were there still in his thoughts. It was a superb race by any standards. He also talked at length to Chris Brasher whom he had met many years before at Alltshellach in Glencoe when they were climbing there.

[I’ll quote again from the source referred to above: “Despite being acclimatised to altitude they (Wolde and Gebru) as well as the others discovered that their performances at the similar altitude in Mecico City were considerably slower than their sea level bests prior to the Olympic Games. The variance ranges from 4 to 17 minutes The primary influencing factor contributing to this slowing is tissue hypoxia (lowered oxygen availabilty) due to the decreased environmental oxygen. The air is 23% less dense than at sea level so it contains 23% less oxygen. Marathon racing is essentially an aerobic event which means runners work to maintain the fastest pace possible without accumulating lactic acid from anaerobic metabolism.”]

Mike feels however that it really had an adverse effect for at least eight years afterwards. When he came home he took part in a two man 5000 metres race with Rex Maddaford. Rex won in a time 5 seconds outside Murray Halberg’s national record – no time was taken for Mike. Two men in a race and the time of the second man wasn’t taken! He reckons he was about 5 seconds back but times were never ever an issue for him. However he found that he had great trouble maintaining fitness. He put in a number of races and would find that he got to a stage in training where he would be reduced to a shuffle, eyes back in his head, looked ill to everybody who knew him and went to the doctor who could find nothing wrong with him. There was some stress in the job he was doing in personnel and human resources. He seemed to recover then he ran in the Hamilton Marathon and won by a big margin mid winter. When he got home he felt awful – lethargic and all the usual symptoms but in mid-winter. Went to bed not feeling well, couldn’t sleep, pacing the floor, his hands on his head and generally distressed. This time the doctor gave him a prescription for 10 litres of electrolyte which he took in one day. And he was fine. Even today he feels it coming on at times and his wife and he himself recognise the signs and he starts seriously drinking water and taking electrolytes.

However you will see from the other notes on Mike on the ‘Marathon Stars’ page that even after Mexico he was winning titles and running well despite the problems he was suffering. No one can ever take Mexico away from him however – the day when despite the Doubting Thomases, despite the injuries and race day problems, he became the only man from sea level to win a medal in an endurance event at the Altitude Olympics.