So what was the actual race day like for most competitors? Well you have to remember that for clubs and runners it had been going on for some time already – like the days of Creation, race day for the E-G was not a normal day of 24 hours! For the E-G the DAY was something like 31 x 24 hours that runners, officials and supporters had been waiting for! Selection was part of that – many club committees picked the last man or two on a trial in a straight race such as the Glasgow University 5 or put them all on the first stage of the Allan Scally. Either was a great folly in my view. In such a trial the guys went head to head and I almost lost out one year to a fast finisher who just sat on me and tried to scoosh past at the finish. Others who should have been in teams missed out because of this kind of trial. One of the big things about the relay was that you were often running in the middle of nowhere and had to judge the pace of the stage from start to finish on your own, or you took over 40 or 50 yards up on the opposition and could not get carried away into trying to drop him with a fast early half to the race – you were not running against who you could see but against the entire race including mainly yourself. A proper selection would have been to put the runners all on the later stages of the Scally when it was impossible to do a straight race against your main club opponent. However, we’ll suppose that you succeeded and made the team.

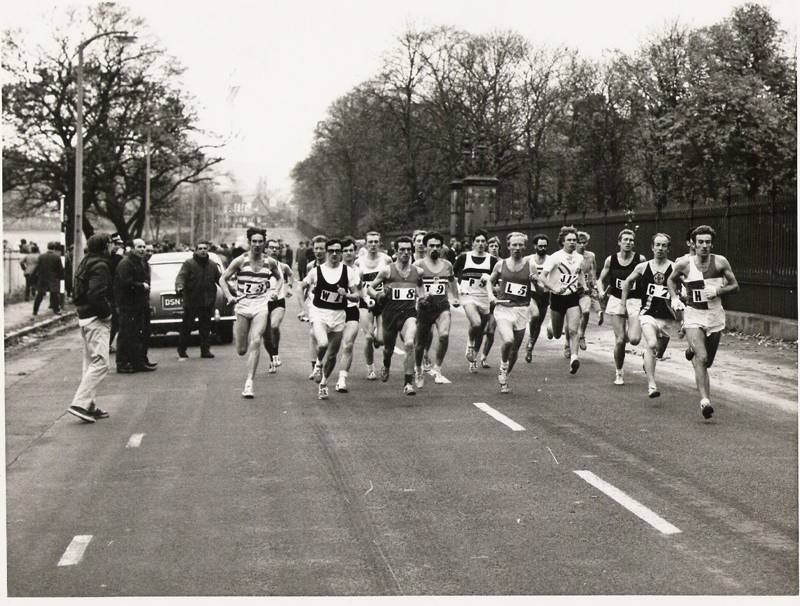

It was up in the morning very early to get to the bus – or latterly your lift – for the journey through to Edinburgh. You felt cold all the way through despite being heavily wrapped. The wrapping was essential because you would be really cold after your leg if you had run it properly and would need several layers on. You might have a flask of soup or coffee or tea plus a couple of sandwiches for sustenance. If you were running third or later you could probably get a tea plus a bacon and egg roll in the cafe just along from the Flora Stevenson School at the start. (That’s another thing – you found out about the geography of central Scotland in terms of toilets available at 5 mile intervals all the way across as well as the occasional tea room. For toilets there had to be one at the start and we used to use those in two swimming pools, at least two pubs and at the start of the fourth stage there was a big cow shed that was always open on race day! It was a VERY educational race!) The atmosphere really started building when you arrived at the starting venue and met guys from other clubs: they all had an “if only…” story. eg if only Jim Anglo had been able to make it up …., if only Jim X hadn’t done in his tendon…. , if only Jim Y’s change of club had come through in time…..(guess the guy’s new club according to your prejudices!) You could hear snippets of conversation like “What shoes are you wearing?”, “Do you think it’s cold enough for a T shirt under the vest?” and so on. Then there was the enigmatic guy who sometimes ran brilliantly and sometimes like unadulterated excrement sitting quietly in the corner -was that a good sign or a bad sign? Was he getting unnecessarily worked up or was he just settling himself for a good run? The the runners were out and warming up – sometimes a runner from the third or fourth leg would do the warm up with his first stage runner. There were supporters everywhere and friends from other clubs who were there asking as usual how you were feeling were today regarded with suspicion: why did they want to know anyway? The runners for the second stage were whisked away early in their bus so that they had time to get warmed up before their start. Atmosphere mounted. The runners were lined up outside the Fettes College Gates, supporters primed their cameras and their lungs, the ceremonial baton was presented to the lead runner of last year’s winning club and the photos taken. A moment of silence and the gun was fired and the runners took off. From the start the trail went a couple of hundred yards in the wrong direction, then a right angle turn to the right, another couple of hundred yards and another right angle turn to the right and straight on to the roundabout before a lind of half left up a longish drag. I usually did nearly a pb 400 yards round that square and still had another 5+ miles to go. Young guys always took that bit too hard – I remember one year coming off the roundabout in about 12th place with young Davie Tees of Springburn in front and Eddie Sinclair shouting at him to steady up a bit but not in those terms! I had him before the second drag. Many young runners – Fraser McPherson of Vicky Park was one and a whole host of University men – were guilty of this. With even minimum experience you knew the opposition and how you were going to run it anyway but sometimes you were thrown what the Americans would call a curve ball. The organisers were guilty now and then of putting in foreign teams and composite teams as a novelty! One year there was a Scandinavian collection and another there was an American group known collectively as the Kangaroos who were composite teams, then there was the Irish Achilles team with the Hannon brothers running; there were teams representing the North of Scotland and one year there was a team of eight good men and true whose clubs would not make the race but they were united to make a composite team. They complicated things a good deal at times but since Scottish athletics is basically predictable in terms of race outcomes they provided a welcome challenge. That typifies the E-G feeling: delight that you were running, dread that you might not be up to the challenge, and a superb feeling of exhilaration if you knew that you had run well and not let anybody down. The E-G was no place for bottle merchants!

The atmosphere was such that you had to really concentrate on doing your own running – if you heard what the supporters were saying you were not doing your job. The first time I ran I was like the rabbit caught in the headlights and didn’t even know where I was placed at the changeover. I thought I was last but I was actually thirteenth or fourteenth – there was no idea how that many people got behind me. They must have hidden up a close (or since it was Edinburgh up a common entrance!) until I passed. You had to be conscious of cars hooting, a lonely bugle blowing more to give the blower something to do to relieve his tension than to encourage someone specific, cars with ambitions to be barbers shaving your legs, the confusion of ordinary Edinburghensians and a general feeling of chaos and you were at the centre of it trying to keep your pace going, keep your awareness of the opposition and NOT BLOW IT. One year I was running five or ten yards adrift of Alex Brown with about two miles to go when Andy Brown appeared at the kerbside shouting to Alex “Two miles to go – nine minutes running!” Well it would be more for me but it meant that the finish was near and if I could relax and work a bit maybe I’d be done in just over 10 minutes. It was a superb but terrifying ordeal and it was the best feeling in athletics to be racing in the E-G! As the first runners came to the one mile to go sign just before the top of the road up from Barnton the first jogging spectators were to be seen – every club had runners who hadn’t made the team but wanted to be part of it out there jogging and shouting and sweating and sometimes swearing at their man – before coming over the top and swooping down the hill to the finish. If you were running well it was a wonderful finish to your leg. Your man there, facing forward but looking backward, club men telling him you were coming when he knew fine well that you were coming. Then crossing the line and before you could do anything for yourself someone would throw a coat, jacket, blanket over your shoulders and march you to the nearest club car unless you could persuade them to let you get your tracksuit from the bus first. Then it was onwards getting out every mile or so to encourage your team mate who wouldn’t actually hear what you were saying but would at least see your encouraging presence!

Joe Connolly with fastest time for the first stage in the post war series handing over to Tommy Mercer in 1955:

Joe McGhee Shettleston) and Pat Younger (Clydesdale) waiting for their runners to arrive.

The second leg runner would travel to his starting point before the first stage started to do his own warm up and get his head right for what was to come. Word would come through that Hamish on the first leg was running a blinder and well up there in the first three or four, then someone else would rush up to let you know that Hamish had totally lost it and blown up (the stupid b*gg*r had started too bl**dy fast as usual!), then just before they arrived over the top of the hill the news would be that he had just come through a bad patch after a good start and was now working his way back through the field. The net result would be that the guy you thought would be eighth or ninth was actually ninth or tenth. You watched your man come in, the sweat was more nerves than anything else, you were clocking where the opposition was (“Damn it he’s 40 yards up on Vicky Park – he should know it’s better for me to be 40 yards down for the handover”), getting a final pat on the back from a club member (why was it only the E-G that inspired folk to pat each other on the back? Scots don’t do pats on the back!), throwing your last top away anywhere when the baton was within reach and then you were in business. There were two lots of people on the second stage – those who deserved to be there as of right like Ian Stewart and company and those who were their club’s last best hope. The former group all knew each other well, had a healthy respect for each other and ran in a confident purposeful manner; the others ran with panic as a companion. Their one real though was please don’t let me be last. Was that Lachie Stewart still warming up for Vale of Leven and starting behind me? More bugles, more club banners, more buses – and more miles for each runner. There was an added issue for the second stage runners – it was A for Anglos! There were several categories of Anglos in the race – those like Hugh Elder of Dumbarton, Bill Kerr of Victoria Park or Jim Dingwall who had gone South for employment or studying and came back for the event and they were OK, there were guys who were bona fide Scots with a longish connection with a Scottish club like Jim Alder at Edinburgh AC and then there were the guys who popped up one year from nowhere and the from time to time for the E-G – guys like the aforementioned Ian Stewart who had no known connection with Aberdeen before he turned up one year to run for them. Then there was Ian McIntosh (or was it Ian McMillan?) who ran occasionally for EAC? I spoke to this guy on our bus who was cheering on one of the Knowles twins but when I asked him which one it was he confessed he didn’t know because he only came up once in the year. These guys were not welcome but when a strange accent was heard at the start of the second leg the question was, was he as good as his running suggested at the start of the run or would he come back later? There was no way of knowing and it also added to the challenge of a race situation that was out of the control of the runner himself.

By now the race was starting to stretch out a bit and there was a rule that any club half an hour behind the leaders would be pulled from the race and although I can only remember one club actually being removed it was a threat. Stages three and four would probably determine in which quarter of the field your club would finish. There was always a temptation to put your weakest runner on the third stage because it was the shortest but there were problems there too – if the weakest runner was in a position where he would have to retrieve ground lost on the second stage, would he be up to it or would the gap be increased to uncatchable proportions? If the weakest runner didn’t run well on hills what would he be like on the severe undulations of the stage? Would it not be better to put him on the seventh? The pressure was still on although the race traffic had thinned out a bit by now, clubs were running in groups and it was possible to make good progress while you were still in the first half of the race. Club officials, supporters and runners who had already done their stint would have watches out, calculating distances between the clubs, deciding whether their man could get the club in front. Whether they thought so or not, they would tell the athlete that he could get his man easily!

The third was important because it was really the last chance for clubs down the order to get back on terms with the main body of the race before the back of the race was broken by the fourth and fifth stages. Like the first stage, there were four fairly serious gradients on the third one and a couple of difficult road junctions. So the runner was doing his best with a diminishing number of cars and supporters vehicles around – for most clubs the first three or four were well away and the officials were wanting to see the front runners. However every group of runners produced a real race. Maybe there were just three or four clubs swapping places but their members were all hoping their squad could make a break and start chasing the next group up. You would pass a carload of supporters from another club that you knew well and they would look at their watches, look at you, look back at their watches and shake their heads. Then you counted the lamp posts until they started cheering on their own man trying to estimate the lead you had on him. Your own men were at the side of the road at least every half mile shouting encouragement trying to give you information that you couldn’t take in. There was no opportunity at any point to just relax and get on with the running. In all the races I ever ran or watched I only once saw a club official having a go at a runner immediately after his run and that was at the start of the fifth stage when the runner was standing exhausted leaning his back on the boot of the car with this fellow haranguing him for not trying hard enough. It was a bit if a disgrace but the supporter was really feeling the pressure and was no doubt getting some therapy from the situation. Another indication of the strength of feeling engendered by the race.

Supporters everywhere – like every club the Trotters tried to be everywhere!

The fourth was usually the third man in the team racing other third men in teams. It was mainly downhill on good surfaces and lots of spots for club cars to stop and help you on your way. There was a huge temptation on this one to go too fast at the start and club support was no help to sensible restraint! The fifth was so exposed – like Rannoch Moor with the rain but without the hills. Whatever weather was going, you got it in spades. Supporters cars tended to be fewer and further apart then on other legs and when you passed them then there was always someone drinking tea from a flask. What didn’t change on either stage was the wee groups of athletes and officials from the opposition .looking at their watches, shaking their heads muttering to each other and generally trying to psych themselves up and psych you out! When you came to the One Mile To Go sign there was a slight turn to the left and the open road seemed to keep going for ever. The relief at the Forestfield Inn was most welcome – goodness only knows what Hughie McErlean thought when his man wasn’t there and he had to keep going for another seven miles!!!

The good thing about the sixth stage was that it was all downhill, the depressing countryside that you ran through didn’t change that at all, the bad thing was that it was seven miles all the way to the War Memorial at Airdrie. Because it was the longest in the race and because the club had one of its very best men on the stage, support was massive throughout this stage! Cars every mile at most, runners jogging along the road between car stops not letting you slack at all, pedestrians in Airdrie, prams in Airdrie, umbrellas on wet days in Airdrie. In 1962 there was even snow in Airdrie with cars abandoned in the main street so deep was the snow. That was the year that Tom O’Reilly said that it was not so much dedication as sheer bl**dy stupidity and who is to say he was wrong? Because of the long bend round to the finish there were often runners jogging on and off the pavement that the racers didn’t see until the last minute and there was a real danger of running into them as well. The support continued, the trumpets continued, banners were still to the fore, clubs that favoured warpaint were still extant. And that trumpet, bugle or whatever it was still disturbed the peace.

The seventh was in many ways the easiest stage – that is a relative term, there was not in any way an easy stage in this race – because it was so far into the race, your general finishing bracket was determined and if you did blow it ever so slightly there was a man running last. It was a good stage on which to ‘blood’ young runners. The bad news was that you passed through Coatbridge. I remember one year passing the five pubs opposite the War Memorial (they had one too) when a drunk approached me and asked for a light. I ignored him and his next remark was “Away ye go, ye baldy yonk!” I didn’t mind the yonk, but baldy? I managed a smile when he swung his boot at me, missed and fell on his back. Not a club supporter there when you need one. It was very important for the club that it finished in the first fifteen to ensure inclusion next year in the race. There was one year when I had the job on this stage and pulled the team up from sixteenth to fifteenth by using what was by then a very auld heid to pull in 2 minutes 45 seconds on the Law runner ahead.

The first year I followed the last stage in the club bus we were well behind Springburn but when we passed Tommy O’Reilly Pat Younger opened the door and looking back past Tommy shouted “Come on George White!” George was nowhere in sight but Tommy almost soiled himself at the thought of having lost that much ground. I also had serious words with a Bellahouston Harrier who was pacing his runner (about 100 yards ahead of Bobby Shields) and giving him regular advice about our man’s position. Pacing is wrong and he was told in no uncertain terms but it was when I threatened to tell Brian Good win that one of his club was behaving in an illegal fashion that he finally backed down. The last stage was about keeping a position but if possible picking one up. On no account was the runner on the last leg to drop a place or it was the big bad burny fire for him. It was also the case that support for the second half of the leg was almost non existent (traffic in the East End saw to that) but the relief at the end was genuine. And the bugle or trumpet was finally silenced.

What a race – although the running race was over, the post mortems, celebrations or whatever the opposite of celebrations is, and so on would last for a couple of weeks and then it would start to pick up in September next year. It is a pity that the race has gone – I would hope temporarily – but we were lucky to have experienced it and even more lucky to have run in it.

“Blessed was it in that dawn to be alive!”