Tom Osler, 1940 – 2023.

Like many of those mentioned as having the answer to the problem of success in long distance (ie further than six miles) running, Tom Osler is now not mentioned or quoted in books or magazine articles on the subject in this country. I that because his ideas are out of date, because they have been assimilated into the mainstream or because they were just plain wrong in the first place? They were nonetheless discussed by runners, male and female, who were interested, in some cases obsessed, with racing effectively in endurance events. Like many of them, he was very intelligent.

The Ultra-Running History Podcast – well worth a read and most of what follows is from that link – tells us about Tom. You should read it, at the very least it will make you think. You can find it at

He was a mathematician, former national champion distance runner, and author. He published his training theories in his 1967 booklet for the ages, “The Conditioning of Distance Runners”. His pioneer 1976 24-hour run in New Jersey, brought renewed focus on the 24-hour run in America. In 1979, together with Ed Dodd, he co-authored UltraMarathoning: The Next Challenge. He is a member of the Road Runners Club of America Hall of Fame.

Osler was an excellent student, but purposely lowered his grades for a while in order to fit in as a “regular guy.” Then the gang in his neighborhood picked distance running as “that day’s form of athletic torture.” Osler jumped in headfirst and started to run. When he was fourteen years old, he had dreams that he would be the first person to break the four-minute mile. He said, “When you are young, you have dreams that seem very attainable.” He did a test mile run and finished in 6:30.

In 1957, Osler went to Drexel Institute of Technology in Philadelphia where he studied physics and won many academic awards. Osler loved running and found time during his busy college life to also be deeply involved with road running. In 1959 he helped found the Road Runners Club of America and was its first co-secretary. He raced multiple times a month in many shorter races put on by Browning Ross (1924-1998) in Philadelphia and throughout New Jersey.

Osler said, “At the time you only ran in a proper athletic setting. You ran in a park or on a track. You certainly never ran on the streets. If you did, you were stared at by everyone.” Yes, he ran on the roads. “Other runners would ask me, ‘how do you stand the ridicule?’ My answer was that I simply ignored it.” Frequently he was stopped and questioned by police while running, thinking he was running to try to get away after doing some crime. Once he was even pulled into a patrol car. Osler said, “He popped out of his car like a jack-in-the-box and tackled me. Before I knew what was happening, I was in the car beside him.” For his first six years of serious running, he raced at every opportunity. In a field of about 50 runners he would finish about 15th to 20th.

But over-training started to plague him. He said, “I had a sciatic nerve condition that left me unable to walk. I still remember going out to train and going so slowly due to hip pain that even the dogs looked at me puzzled. They couldn’t decide if I was running or not and were confused as to whether to chase me.” He soon figured out that rest and healing was just as important as training. In 1963 after reading Running to the Top by Arthur Lydiard, he adopted the method of slow training and took his first “great leap forward.” He started to run steady miles, often reaching 70-75 miles a week, much of it on the road. As he coached himself, some wins started to come and he finished the 1964 Boston Marathon in 2:47.

Osler became life-long friends with future American ultrarunning legend, Ed Dodd, in the early 1960’s when Dodd was still in high school. They would do long training runs together. In 1965 at the age of 25, Osler was “beaten soundly” by Dodd, age 19, who became captain of St. Joseph University cross-country team. This increased Osler’s motivation and “the old competitive zeal was put into high gear.” In July 1965, Osler went to Falls Church, Virginia, to compete in a one-hour track run against a highly competitive national field. He hoped to finish in the top ten. He ran away from the field, lapping them and won with 11.3 miles. He became highly ranked in the nation for 1965 and won the 25 km national championship. He raced nearly every weekend and won about 30 races in 1965 for distances from 3-15 miles, both on roads and cross-country .

In 1967 Osler was inspired by Ted Corbitt to give ultramarathons a try. With running buddies, Neil Weygandt and Ed Dodd, he began doing 50-mile training runs from Collingwood to Atlantic City, New Jersey. On August 13, 1967, Osler won a club 40-mile fun-run in Egg Harbor, New Jersey. Confident that he could do well, he began preparing to run in the 50-mile national championship to be held in November 1967. He worked up his runs to 55 miles. He ran every afternoon after classes covering 75 to 80 miles a week and averaged 7.5 minutes per mile.”

And it is as an ultra runner that Tom is best known. He won the National AAU Marathon in 1964, the National 30K championship in 1967. In 1967 he also won the National RRC 50 Mile title and ran his best ever marathon in 2:29:04 at Boston and was fourth in the National AAU Marathon in Holyoke. He later completed a 24 hour run covering 114 miles. He had found his events. How did he train for them? He wrote a slim book in 1966 called ‘The Conditioning of Distance Runners’ where he said that distance running training should be at a comfortable pace 90% of the time. Remember that in the 60’s many were running intervals four or even five times a week. Lydiard was being accepted as the top coach at the time and Osler adopted and adapted a lot of Lydiard’s thoughts into his own training. He wrote another (lengthier) book called ‘The Serious Runner’s Handbook’ in 1978. The 32 pages of his first book had turned into 180+ and had much more information.

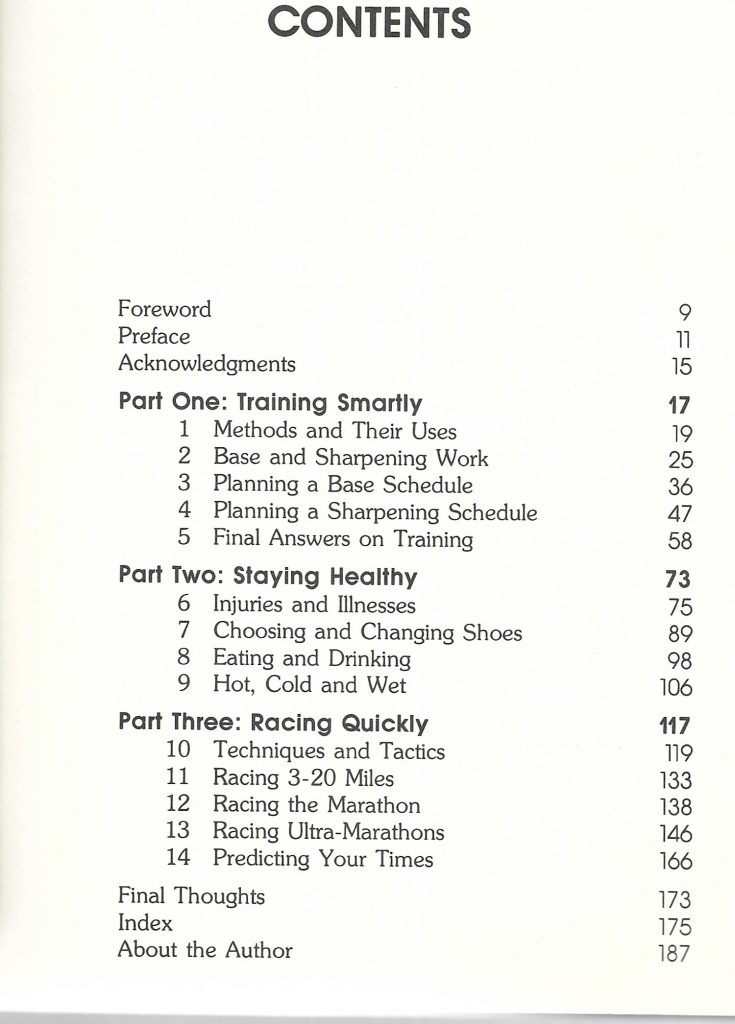

Divided into three parts – Training Smartly, Staying Healthy and Racing Quickly – 40 pages are devoted to training which in itself has 5 sections – Methods and their Uses, Base and Sharpening Work, Planning a Base Schedule, Planning a Sharpening Schedule and Final Answers on Training. Part Two deals with injuries and illnesses, shoes, eating and drinking and the weather. Part Three covers Techniques and Tactics, Racing 3 – 20 miles, Racing the Marathon, Racing Ultra Marathons and Predicting your times. It is maybe an idea to look at the first part first.

He starts by laying out five types of training

- Walking: ie walking at a brisk pace pace of 3 – 4 miles an hour. (NOT heel-and-toe race walking!)

- Running mixed with Walking: ie. A mixture of running and walking enables an athlete to cover immense distances with little fatigue. For instance, he says, a well-trained runner could cover 40 miles in training by alternating 2 miles in 15 minutes and then walking a quarter mile in 4 minutes.

- Long, slow continuous runs which he says develops the cardio-respiratory system. The slow pace is less likely to injure muscles and tendons which is not the case with faster running.

- Interval Speed Runs. After a definition of fast repetitions with intervals, he tells us that this enables the runner to relax well at a faster pace.

- Fast, long, continuous runs. After saying it is the hardest form of training, he describes what he means by this. The runner selects a distance – usually 5 to 15 miles – and runs it in training at a pace which is close to his racing pace.

Before going on to Base and then Sharpening Work, he credits Lydiard with being the source of modern training methods. When he describes his own methods of training and rationale for them, there is however a similarity between them although they are different.

Base Training: The runner’s base level is the result of his inherited endurance and his own experience of endurance related activities (walking, cycling, swimming, running, ski-ing, etc). The point of Base Training is to develop the cardio-respiratory system to increase the overall endurance of the runner. It is important, he says, to maintain a relaxed and non-competitive atmosphere and not burn up the runner’s nervous energy. It can be done at any time and can also be a health generating activity for almost anyone. If a runner has done his sharpening training, he should return to base training. Base Training should last for at least six months, preferably a year, before sharpening training begins. He should not run the same distance every day, walking during some of the runs is allowed (even encouraged) and suggests the following of one way of doing this:

| DAY | LENGTH | DISTANCE RUN |

| Monday | Short | 5% of week’s total |

| Tuesday | Medium | 15% of week’s total |

| Wednesday | Long | 30% of week’s total |

| Thursday | Short | 5%of week’s total |

| Friday | Medium | 15% of week’s total |

| Saturday | Medium or Short | 10% of week’s total |

| Sunday | Time Trial or Race | 10% of week’s total |

He also points out that some runners do hard day, easy day, hard day, easy day, . . . a pattern that is also very effective. He also says that with the exception of the time trial or race, all these runs should be at a comfortable or relaxed pace. Certainly one should not be running so fast that continuous conversation is difficult.

The purpose of the race is to remind the runner of the race pace because the training is done at a slow pace. The long run is to help the circulatory system and give the athlete the experience of staying on his feet for a long period of time. The runner begins this period with a low mileage of 30 miles per week which is gradually increased until the long run is about 22 to 25 miles.

Sharpening training: The sharpening training begins about 6 weeks before the race in which the runner aims for peak performance. This is much more difficult for two reasons: (a) There is a greater strain placed on the runner’s body and resistance to illness is less. (b) Great care must be paid to every aspect of sharpening or a low peak or even complete failure will result. A typical week would look lie this.

| Day | Training |

| Monday | Easy |

| Tuesday | Relaxation – Speed Workout |

| Wednesday | Moderately long easy run |

| Thursday | Relaxation – Speed Workout |

| Friday | Relaxation – Speed Workout |

| Saturday | Medium Easy Run |

| Sunday | Race or Time Trial |

What’s a relaxation – speed workout? The aim is to run at speed and stay relaxed. The emphasis is on relaxation and only secondarily on speed. eg in the first week of this period he would cover the distance of his previous medium runs, in this case 12 miles, as follows: the first three miles at base training speed of 7:30 per mile; during the fourth mile he does four fast breaks of about 50 – 100 yards; during the fifth mile, he does a long build-up of between 880 to 1320 yards; during the sixth mile he does 4 x 50 – 100 yard breaks; in the seventh mile he does another half mile build up; in the eighth it is another 4 sets of 50 – 100 yard breaks; ninth another half mile build up; the last three miles are at base training pace with another 4 x 50 – 100 yards. The workout centres upon the 3 half mile breaks. The 4 x 50 – 100 breaks are never at full speed which implies straining and a poor running action but he can attain near maximum speed in a relaxed fashion. The load is increased as follows:

| Week | Increase |

| First Week | 3 x 880 yards |

| Second Week | 3 x 880 yards plus 1 x 440 yards |

| Third Week | 4 x 880 yards |

| Fourth Week | 4 x 880 yards plus 1 x 440 yards |

| Fifth Week | 5 x 880 yards |

| Sixth Week | 5 x 880 yards plus 1 x 440 yards |

| Seventh Week | 6 x 880 yards |

Osler goes on from here to talk about how you know the sharpening is working, what signs to look for as it progresses, how to adapt training if there are any problems, etc. The best way to find out what he meant is to buy the book – less than £4 on eBay – and read it. We could only skim the surface here. The list of contents below will tell you whether you want to buy it – less than £4:00, postage paid on eBay!

His name is unknown to many – most – Scottish distance runners but he did have an influence, especially in the 1970’s when many top marathon runners produced books describing their training and its rationale. Where Osler was different was in the amount of time he devoted to long, slow distance running. A very intelligent man, his book covers every aspect of distance running that anyone could conceivably be interested in and in detail but in language that every runner could understand.