The Scottish Association of Track Statisticians (SATS) have posted annual best performances (usually top ten Men’s times) from 1959 to 2017. In addition, a Scottish Athletics Yearbook was published from the 1960s to the 1990s – and this includes approximately a top forty. Examining these statistics gives clear evidence of improvement (or, during a number of years) deterioration in times achieved.

In this article, the intention will be to consider probable reasons for improvement or deterioration in performances:

- before the 1970 Commonwealth Games course was used;

- during its use for the Scottish Marathon Championship;

- afterwards until ‘Big City Marathons existed;

- during the 1980s ‘Marathon/Jogging Boom’;

- and since the disappearance from the fixture list of so many Scottish (and British) marathons.

Although the Scottish Marathon Championship started in 1947, no settled course was used. Footwear could be unsupportive and only a fairly small number of hardy amateurs took part each year. Joe McGhee (1956) and Harry Fenion (1957) reduced the Championship Best Performance to 2.25.

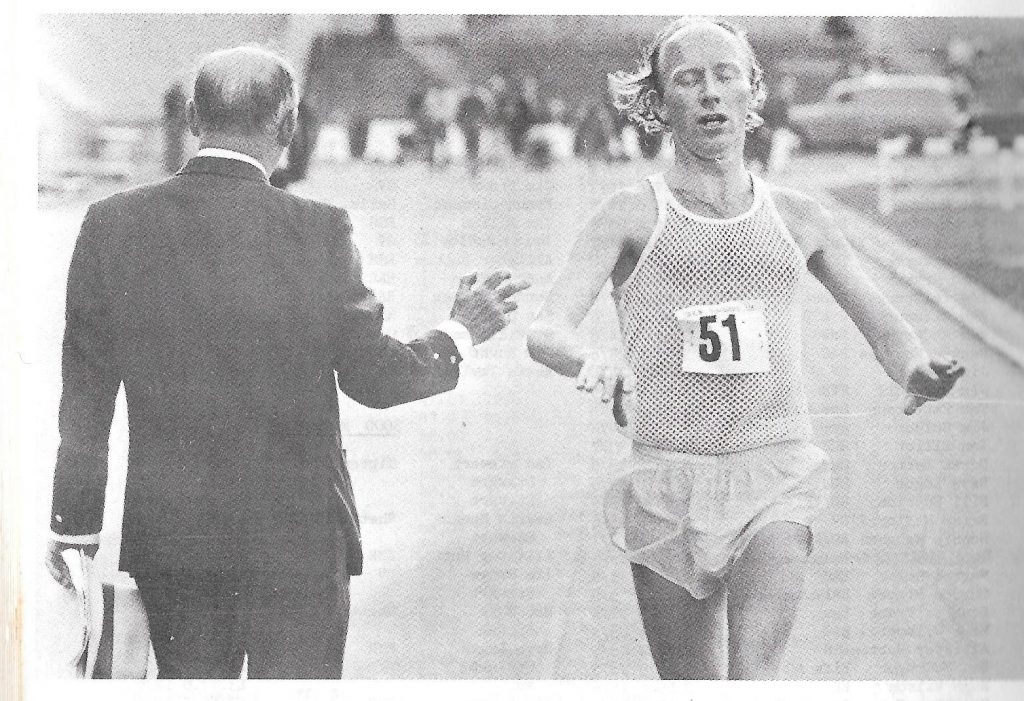

However, it took until 1965 for three, or in this case four men to break 2.30 in the same Championship (Alastair Wood (2.20.46), Donald Macgregor, Charlie McAlinden, Hugh Mitchell). Ron Coleman ran 2.28.04 in Aberavon. Earlier in 1965, the Shettleston Marathon had allowed Fergus Murray (2.18.30) and Wood (2.19.03) to become the first Scots to break 2.20 in Scotland. The ranking list shows an unprecedented six Scots under 2.30.

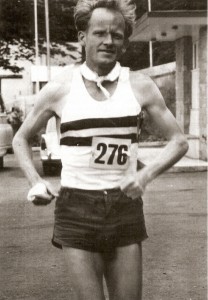

Top Scottish marathoners, at this time, had a choice of three marathon courses: the Scottish, Shettleston and Inverness to Forres. There was also the opportunity to race in England at the Polytechnic or another, often fast, course which might be used for the AAA Championships. In 1967 at Nuneaton, Scots were the first three finishers in the AAA event: Jim Alder (2.16.08), Alastair Wood (2.16.21) and Donald Macgregor (2.17.19).

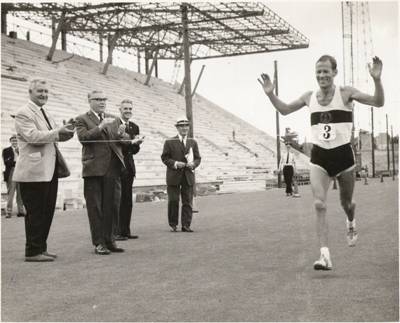

The 1970 Edinburgh Commonwealth Games Marathon course, when the weather was kind, was undoubtedly fast. It was first trialled in 1969, but the 1970 Scottish Marathon Championship, which was the Trial for the Scottish CG team, showed real progress. Jim Alder set a Championship Best Performance of 2.17.11, with Donald Macgregor, Fergus Murray and Alastair Johnston also under 2.20. Tenth man home ran 2.25.27! In the actual Commonwealth Games event, Jim Alder finished a valiant second in a new Scottish National Record of 2.12.04. The Yearbook shows that, in 1970, five Scots ran sub 2.20; another ten sub 2.30; and a further five sub 2.40.

What factors may have allowed Scottish Marathoning to improve to this good level? Certainly, the fast 1970 course, but aspiring marathon racers could peak gradually by building up fitness from early September, not only through fast, short cross-country relays but also road relays culminating in the prestigious and enormously popular Edinburgh to Glasgow 8-Man Road Relay. On New Year’s Day, there was the 14 Miles Morpeth to Newcastle road race. Shortly after, the 5 Miles Nigel Barge race. After stamina-testing Cross-Country Championships, there ensued many traditional road races (often linked to Highland Games) over distances from ten to 22 miles. On the track, 5000m and 10,000m races increased speed and tactical awareness, while the Scottish Ten Miles Track Championship might be another stepping stone. At the end of June, the Scottish Marathon Championship was a major target. In early Autumn, another marathon might be attempted. If not, a brief rest – and then the Road Running Year would start afresh.

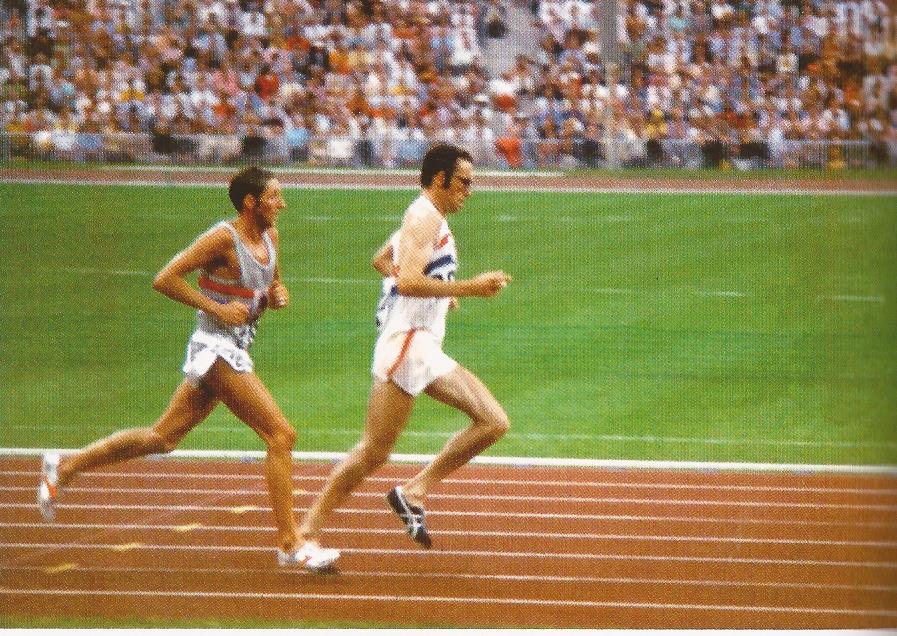

From 1971 to 1980, the Scottish Marathon Championship continued to take place (on the same potentially fast course) during the Track and Field Championships at Meadowbank, Edinburgh. Consequently, a good standard was maintained. Donald Macgregor finished an excellent seventh in the 1972 Munich Olympics Marathon. The Scottish Championship record was lowered to 2.16.05, first by Colin Youngson (1975 – 2.16.50) and Jim Dingwall (1977). In the latter year, the first four in the Scottish Marathon broke 2.20, making a total of six in the Yearbook. First Sandy Keith, then Jim Dingwall took over from Donald Macgregor as Scotland’s best marathon man.

Change started happening in 1979, when the first Aberdeen and Glasgow Marathons commenced, followed by the most important factor of them all – the London Marathon – in 1980. As the number of runners contesting London increased, times became ever faster, due to the long mainly downhill early miles and groups sheltering from any headwind while hanging on grimly! Gradually, cash prizes became available, In London and fast events abroad, such as Rotterdam, Boston and New York. Semi-Professional athletes appeared; and domination by ‘Serious Amateurs’ ended.

In Scotland the same traditional events continued to exist, allowing ambitious young marathon runners to peak in a structured manner: short relays, longer ones, cross-country, track and longer road races. As Big City Mass Marathons, developed, finishing times improved for Scottish competitors.

Yet the lure of such events ensured loss of status for the Scottish Marathon Championship itself. The 1970 CG course was last used in 1980. A slower Edinburgh course was used in 1981 Another fast course from Grangemouth was used only in 1982; a slower Edinburgh course was used in 1983; the 1984 Scottish Marathon was farmed out to a reasonably fast course in Aberdeen; and the 1985 event, on another slower course in Edinburgh, was the very last one to take place along with the Scottish Track and Field Championships. Thereafter, the Scottish Marathon Championship was doomed to wander, a pale shadow, to courses which were usually rather slow, as part of events like Inverclyde, Lochaber, Elgin, Loch Rannoch and Loch Ness. 1982 was the last time that the winner ran under 2.20 (apart from the 1999 heavily-sponsored event, when three foreigners took the medals) until 2009, when Martin Williams ran 2.18.24 in the Edinburgh Marathon.

The 1980s Marathon Boom undoubtedly produced many fast times for many Scottish runners, even if the Glasgow Marathon (and its fast course) ended in 1987) and Aberdeen (on a much slower version than the one used between 1980 and 1984) was last run in 1990. Dundee (1983 to 1991) could also be fast, unlike several other, fairly short-lived Scottish marathons.

Most fast times by Scots were achieved in Glasgow and London. The ranking lists show the following.

1980 was the first time that more than ten Scottish Men ran under 2.20. John Graham set an excellent new Scottish record of 2.11.47 at Rotterdam; and bettered this mark at the same venue in 1981: 2.09.28.

In 1982, 18 broke 2.20; 46 2.30; and 70 were under 2.40. Compare that with 1970! By 1983, 2.17.33 was only good enough for tenth in the ranking list. In 1984, tenth fastest was 2.17.04. That was as fast as tenth place ever got, although ‘best ten times under 2.20’ was also achieved in 1985, 1986 and 1987 – but this never happened again, right up to 2019.

A new breed of fast Scottish marathon runners thrived during the boom years: John Graham, Graham Laing, Andy Robertson, Dave Clark, Fraser Clyne, Lindsay Robertson and, later on, Peter Fleming. (Paul Evans, mysteriously, topped the list twice, but raced for England, never Scotland.) In 1985, Allister Hutton set a Scottish National record (2.09.16) that lasted until 2019. In 1990, famously, Allister Hutton won the London Marathon.

(This article focuses on Scottish Men’s marathon running; but the Scottish Women’s Marathon Championship started in 1983 – and many Scottish female athletes have shone brightly in the marathon, including Leslie Watson, Lorna Irving, Lynda Bain, Lynn Harding, Liz McColgan, Karen McLeod, Trudi Thomson, Lynne MacDougall, Susan Partridge, Kathy Butler, Hayley Haining and Freya Ross. However, their story is for another article.)

Gradually, the slide in Scottish Men’s marathon standards began. By 1990, tenth in the rankings meant 2.28; by 1995, 2.33. In 2004, 2.38. Yes, a few top racers appeared, such as David Cavers and Simon Pride, but there was no doubt that times were much slower, not only when compared to the 1980s, but also to the 1960s!

What factors might account for this?

- A lack of fast marathon courses in Scotland and, apart from London, in England

- 1987 being the last year when Scotland could compete as a separate nation in the World Cross Country Championships – which had been a major ambition for good distance runners, who later turned to the marathon

- The Edinburgh to Glasgow Relay last being run in 2002. Like so many other traditional relays and road races, the police or local councils no longer granted a permit – using as unconvincing excuses expense or safety

- In the Scottish fixture list, a lack of structured training opportunities for road racers to gain speed and stamina in time to peak for important goals (which used to be the E to G in November and the Scottish Marathon Championships at the end of June)

- Mass Marathons led to fun runs and the mistaken notion that a sub 3 hour marathon is an excellent performance, even for physically talented men in their 20s and early 30s

In 2010 (for the first time since 1998) there were two Scots under 2.20! Ludicrously, in that year, the so-called Scottish Marathon Championship became part of the London Marathon. However, Andrew Lemoncello finished first Briton in 8th place and recorded 2.13.40 – the fastest time by a Scot since Peter Fleming in 1995. Martin Williams ran 2.17.36.

Since then, although Derek Hawkins, Ross Houston, Callum Hawkins, Michael Crawley, Tsegai Tewelde and Robbie Simpson have produced sub-2.20 performances – and, in some cases, run much faster than that mark – tenth fastest in the yearly rankings continues to hover around 2.30.

Therefore, a few Professional Scottish Male Athletes (especially, Callum Hawkins, who in the 2019 London Marathon broke Allister Hutton’s record with a superb 2.08.14) are still capable of running very fast and competing well in Commonwealth, World or even Olympic marathons. Otherwise, the overall depth of Scottish Men’s marathon running continues to be unimpressive. More support from the Event Calendar would help enormously, with just a few significant alterations.

HOW MIGHT THE DEPTH OF SCOTTISH MARATHON RUNNING BE IMPROVED?

EACH ASPIRING MARATHON RUNNER WILL NEED TO CHECK THE CURRENT SCOTTISH FIXTURE LIST.

At present (assuming that road running is possible, after the coronavirus pandemic), the Scottish Athletics fixture list includes the following:

From the beginning of the Cross-Country Season (October 1st) are there any other short, fast ROAD relays?

District Cross-Country Relays (mid-October)

Scottish Cross-Country Relays (Cumbernauld, end of October)

Allan Scally Memorial Road Relay (4x5k) (Glasgow Green, end of October)

Scottish Short Course (4k) Cross-Country (early November)

District Cross-Country Championships (early December)

ARE THERE ANY ‘TRAINING’ ROAD RACES IN DECEMBER/JANUARY?

Scottish Inter-District Cross-Country (Stirling, early January)

Scottish National (10k) Cross-Country (Falkirk, end of February)

Scottish 6-Stage Road Relay (Livingston, end of March)

Scottish 10 miles (Motherwell, also end of March)

Scottish Marathon Championship (Stirling, end of April – but a slow course) LONDON IS MUCH FASTER.

Scottish 5k (Edinburgh, early May)

Scottish 10k (Stirling, early September)

Scottish Half Marathon (Glasgow, end of September)

[The Scottish Road Running Grand Prix was aligned with all of the Scottish Road Championships at 5K, 10K, 10 miles, 1/2 marathon and marathon and the final score is calculated with the best 4 out of 5 races. (Therefore, decided after the Half Marathon, end of September.)]

CONCLUSION:

Although Scottish Athletics and British Athletics does support a very small number of Elite or Near-Elite Scottish Marathon runners, the existing race calendar does NOT seem to support aspiring road-racing athletes who wish to a) improve and achieve a fairly good marathon time and possibly b) improve further to sub 2.20 or faster and then c) JOIN the Elite and receive funding to make them truly competitive. (Cross-country, track and shorter-distance road runners are reasonably well catered for; but not marathoners.)

ROAD RUNNING PEAKING CALENDAR: SUGGESTIONS:

(TO IMPROVE THE DEPTH OF SCOTTISH MARATHON RUNNING)

It is logical that a fairly young (up to mid-thirties) aspiring Scottish marathon runner (aiming at sub-2.30 or even sub-2.20) may wish to compete in a) a Spring Marathon and b) an Autumn one.

Obviously, each aspiring marathoner should be following an appropriate training schedule (including a longish Sunday run (steady or varied effort 10 miles gradually increasing to 16 and occasionally 20), easier recovery runs, faster work – long reps, fartlek, road hill reps, time trials/hard effort parkruns ); and should include carefully selected ‘training races’ to improve speed and stamina, then tapering for two weeks to ensure freshness before a target marathon. (For sub-2.30, a talented youngish runner might average 60-70 miles per week (including these ingredients every fortnight), while for sub-2.20 (on a fast course, with sensible tactics and considerable luck!) 80 mpw might be more suitable. Some runners go for 100, but the ‘ideal amount’ depends on the resilience of each individual.

END OF MARCH/VERY EARLY APRIL: TEN MILES ROAD RACE (TOM SCOTT?); PLUS A HALF MARATHON OPTION REQUIRED. (NO NEED FOR CLASHING SIX STAGE ROAD RELAY HERE. The National XC in February serves as a non-road-running target for this part of the season).

END OF APRIL OR EARLY MAY: FAST SCOTTISH MARATHON REQUIRED; OR PEAK FOR LONDON END OF APRIL.

JUNE, JULY AND EARLY AUGUST; MAJOR TEN MILES OR HALF MARATHONS REQUIRED. EXCELLENT ‘TRAINING RACES’ to show top potential for the Marathon. A road race of 18 or 20 miles would also be excellent pre-marathon preparation. Perhaps the Edinburgh to North Berwick might restart?

EARLY SEPTEMBER: STIRLING OR EDINBURGH MARATHON (= SCOTTISH CHAMPIONSHIP). ALTERNATIVE TO GREAT SCOTTISH RUN HALF MARATHON IN GLASGOW. OTHERWISE, THERE WILL BE A NEED TO TARGET A FAST EUROPEAN MARATHON.

OCTOBER: THE SCOTTISH CROSS-COUNTRY RELAYS TAKE PLACE AT THE END OF OCTOBER; WHY NOT SHIFT THE ALLAN SCALLY RELAY TO MID-OCTOBER TO BE A ‘TRAINING RACE’ FOR ROAD RUNNERS?

SHIFT SIX STAGE ROAD RELAY TO MID-NOVEMBER (= MAJOR ROAD RUNNING TARGET LIKE E TO G FOR FIRST HALF OF SEASON). THEN TRAINING FOR NATIONAL CROSS COUNTRY, FOLLOWED BY MARCH TEN MILES/HALF MARATHON, THEN LONDON OR POSSIBLE SCOTTISH ALTERNATIVE.

Recently, the Scottish Athletics Marathon Project has been set up, under the direction of Robert Hawkins (who coaches his talented and very successful Elite sons, Derek and Callum). The aim is to boost Scottish marathon standards before the next Commonwealth Games. A maximum of three Scots can be selected for that, but several other aspiring young Scottish marathon runners have been included in the Project. Although Coronavirus has delayed developments, everyone has access to a fund if they require physiotherapy. Some runners are entered for the Wrexham Elite Marathon in early October, and personal bests may result.

Would it be possible for the Scottish Athletics Marathon Project to consider the suggested adjustments to the Events Calendar to encourage even more up-and-coming Scottish Road Runners and Marathoners to improve their times and be considered for training camps and selection? Wouldn’t it be great to see the DEPTH of Scottish Marathon running return to the standards of the 1980s?

Previous Parts of this Post: Part 1 Part 2 Part 3